His Majesty in His Closet

His Majesty in His Closet: Chapel Closets and the Construction of the Jacobean Royal Image

By Oscar Patton

Abstract

Closets played a prominent role in the devotional life of the early Stuart court, where they offered a small space for prayer, liturgy, and diplomatic engagement for the monarch and other members of the royal family. The chapel closet, overlooking the household chapel, was the most prominent of these spaces and regularly hosted the guests invited by the monarch and members of the royal family. Intimacy and access mattered in the early modern court. Being able to speak, touch, and hear the king was a mark of privilege and potential influence. This article examines surviving evidence from the Great Wardrobe Accounts, pictorial representations, and a handful of surviving eyewitness accounts of services to reconstruct the internal environment and appearance of James’s chapel closet. James spent far more than Elizabeth I on the furnishings of his closet and limited its ceremonial use to members of the royal family. While the Jacobean chapel closet has been closely associated with the rise of prominent churchmen in favour of greater church beautification such as Richard Neile, clerk of the closet between 1603 and 1632, the article argues that this prominent courtly space reveals an energetic pattern of material splendour promoted from James’s accession that was closely connected to his personal conception of his English kingship.

For Protestant and Catholic monarchs alike, prayer was central to the maintenance of the royal image.1 This was both a public and a private act, as a monarch had to be seen participating in the rites of the church. In post-Reformation England, the supreme governor of the Church of England’s public performance of the rites and ceremonies of the church over which they had authority was a matter of both royal majesty and confessional politics. Royal prayer could happen in several separate courtly locations. By far the most prominent was the palace chapel, where on communion days the monarch appeared in the sanctuary of the chapel before prominent noblemen, clergy, and household officers. A more regular location, however, was the chapel closet, a space just under half the size of the chancel of palace chapels, which had a large oriel window to permit visual access from the closet into the chapel. From this vantage point, the monarch observed services and celebrated separate services of communion and morning and evening prayer, at which attendance was strictly limited.2 The monarch also prayed in a different sort of closet, known as the “privy” closet, where services of prayer for the monarch and their most intimate companions could be heard, devotional manuals read, and paperwork and correspondence completed.3

1This article focuses on the chapel closet, which joined the palace chapel as a prominent spatial point in the processional route taken by the monarch, the royal family, chief household officers, and each nobleman or prominent ecclesiastic present each Sunday, while the court was in residence. On these occasions, the monarch would process from their bedchamber, through the privy chamber, into the presence chamber (where courtiers and nobles would join the processional train), through the great hall, and through the chapel gallery towards the chapel. Here the monarch and their train split off and entered the closet, which was divided into the sovereign’s and consort’s “sides”; the nobles descended into the body of the chapel; and other courtiers entered the antechapel through the ground-floor door to the chapel. Only members of the royal family and the bedchamber, visiting potentates, select ambassadors, and favourites would remain with the monarch in the closet.4 Although scholars have paid attention to the importance of court ceremonial in arranging the space and furnishings of certain areas in the early modern court, the chapel closet has not received the same level of attention, partly because of a perceived absence of available sources.5 This article draws primarily from surviving evidence in the Jacobean Great Wardrobe accounts, with additional perspectives from courtly diaries and accounts of ceremonial events, and the highly stylised representation of intimate closet-like spaces in certain royal portraits, paintings, and illuminations.

4Early modern courts had several different types of closet. When monarchs are described as hearing prayers in their “closet”, it is sometimes unclear as to whether this was the chapel closet, which overlooked the court chapel, or the “privy” closet, which adjoined the presence chamber.6 With the exception of a handful of eyewitness accounts of services in the chapel closet, and descriptions of the monarch’s behaviour in this space from court ordinances, the chapel closet has remained a space of relative ambiguity in the early modern court, especially compared with other spaces reserved for elite personages such as the privy, presence, and council chambers, or the court chapel itself.7

6Chapel closets were religious spaces, and they have, by consequence of the confessional identity and career of James’s only clerk of the closet, Richard Neile (clerk between 1603 and 1632), been associated with the patronage of a particularly ceremonial liturgical style.8 Peter Lake termed this style of churchmanship “avant-garde conformity” as an alternative to the theologically limited “proto-Arminian” or politically misrepresentative “proto-Laudian”. Avant-garde conformists encouraged more religious images and music in public worship, and tended to focus on a sacramental style of piety which valued the Prayer Book service over strict predestinarianism and the elevation of the preached word.9 While Richard Neile was an avant-garde conformist par excellence, the absence of decisive evidence makes his influence over the chapel closet difficult to reconstruct.10 He was probably involved in the purchase of materials for the chapel closet, but such items should be interpreted as part of a wider programme of James’s material majesty rather than as the exclusive personal influence of an individual churchman. The appearance of ecclesiastical spaces was the subject of heated debate in the early seventeenth century, but royal venues enjoyed a heightened level of material, visual, and sensory splendour that accorded with the sacral presence of the monarch, even in Protestant courts. As such, while avant-garde conformists might find happy employment within such venues and institutions, such spaces were primarily royal environments, where the will of the monarch directed or at the very least influenced the fabrics used to decorate them.11

8Chapel closets simultaneously restricted the visibility of their occupants and elevated them above the congregants gathered in the antechapel and chapel stalls below. From the ground floor of court chapels, noblemen and women, privy councillors, and chief household officers (the only members of court formally permitted to sit in the chapel stalls), alongside their attendants seated on benches and stools next to the stalls, could see the monarch and their companions through the closet’s central oriel window.12 Space was a central component of early modern royal performance, and the distinction of the monarch’s body from other courtiers, and moments of visible proximity and intimacy, contributed to the creation of a highly visible politics of access.13 The chapel closet was, therefore, a performative space, which combined the elite publicity of court ceremonial with the intimacy typically associated with closets and adjacent spaces that were reserved for the individual’s intimate devotions, correspondence, prayer, and reading.

12James’s style of kingship thrived in intimate spaces, where he was able to perform in front of a small group of select councillors, favourites, and guests.14 This made his chapel closet a prime venue for his preferred form of political interaction. James also appreciated the importance of prominent religious venues where he could demonstrate his participation in the rites of the Book of Common Prayer. This was an important step in securing the confidence of the English ecclesiastical hierarchy and political establishment, who feared that a Presbyterian king might transpose the Scottish kirk to his newly acquired southern kingdom.15 Chapel closets were an essential part of religious practices at the early modern English court, and their appearance, as well as their ceremonial use, formed an important aspect of how the appearance of kingship was constructed. James’s approach to intimate venues of courtly worship, such as the chapel closet, provides a means of understanding how he wished to present himself as a Calvinist monarch comfortable with the material splendour of his royal office, both to his courtiers and to an international audience of diplomats and envoys.

14James invested enthusiastically in the furnishings of his chapel closets to bolster his image as a king conformable with the Prayer Book liturgy and as a monarch surrounded by the splendour appropriate to his multiple kingdoms, ecclesiastical governorship, and sacral authority. James embraced his inherited tradition of royal splendour in religious spaces from his medieval English and Scottish predecessors. Chapel closets were an essential part of English kingship from at least the reign of Henry III, as they offered a separate space for the monarch and their family to observe services in the royal household chapel and further contributed to the physical distinctions necessary to support an increasingly sacral style of kingship.16 During the reign of Henry VIII, closets were repositioned to the west end of chapels, which allowed the Tudor king and his successors more space to accommodate their retinues, family members, and guests, and permitted a greater degree of internal and external elaboration, as a unified facade was presented to congregants outside the closet.17 It is perhaps no coincidence that the accession of the first monarch with children to the English throne since Henry VIII saw a revival of the chapel closet as a key locus of material investment and decoration. It was not only the presence of a royal family that resulted in changes in the use of the chapel closet. James actively altered Elizabethan practices to suit his distinct habitation of the closet, implementing an alternative programme of material display to both aid physical comfort and demonstrate his splendour as a leading Protestant monarch among the courts of Europe.

16This article begins by recovering how James engaged with his chapel closets and their arrangement, location, and ceremonial function, in both England and Scotland. It also contrasts Jacobean courtly ceremonial with those of his English predecessor and of his princely contemporaries across Europe. Following this, the material decoration and accoutrements of worship purchased for James’s closets are described in the context of his conscious efforts to modify more intimate devotional spaces at court to serve his political and confessional needs.

As a monarch brought up among Calvinist and Presbyterian churchmen who promoted a pared-down aesthetic of public worship, James subverted initial English expectations by continuing and further investing in the materially and sensorially splendid style of worship cultivated by English monarchs. This elaborate style of worship offered a model for liturgical performance that some prominent churchmen, including Lancelot Andrewes (dean of the Chapel Royal 1618–26) and Richard Neile, promoted in contexts beyond the royal court. While this decorative scheme may have pleased avant-garde conformists such as Andrewes and Neile, it was part of an older feature of English royal decoration and was not exclusively directed by ceremonialist concerns regarding wider church decoration in the early seventeenth century. James was convinced of the divine authority invested in the royal office. Consequently, his decorative motivations for the small and exclusive space of his chapel closet were led not necessarily by Calvinistic or avant-garde conformist principles but by a commitment to the majesty of his office, the accommodation of a large royal family, and the heightening of international Stuart prestige.

Closet Function, Use, and Access

Study of the Jacobean chapel closet is hampered by a perceived absence of evidence. Relatively little has been written on its institutional role and structure, and few eyewitness accounts survive for the services and ceremonies that were performed within it. The most valuable resource for recovering the decoration of chapel closets are the surviving records in the Lord Chamberlain’s and Auditors of the Imprest’s accounts, which reveal the fabrics and materials purchased for the Great Wardrobe. Such details can help to reconstruct important visual, sensory, and ritual aspects of this important ecclesiastical space. It is almost certain that the “closet” referred to in these accounts is the chapel closet rather than the “privy” closet because entries for the closet’s materials regularly appear in close proximity to the “stuff” purchased for the chapel and are occasionally combined in the same entry.18 Furthermore, surviving warrants ordering for the payment for “stuff” for the chapel closet from the 1590s and early 1600s, held in the British Library, record the receipt of these goods by the clerk of the closet, which accord with the annual receipts recorded in the Lord Chamberlain’s and Auditors of the Imprest’s accounts.19

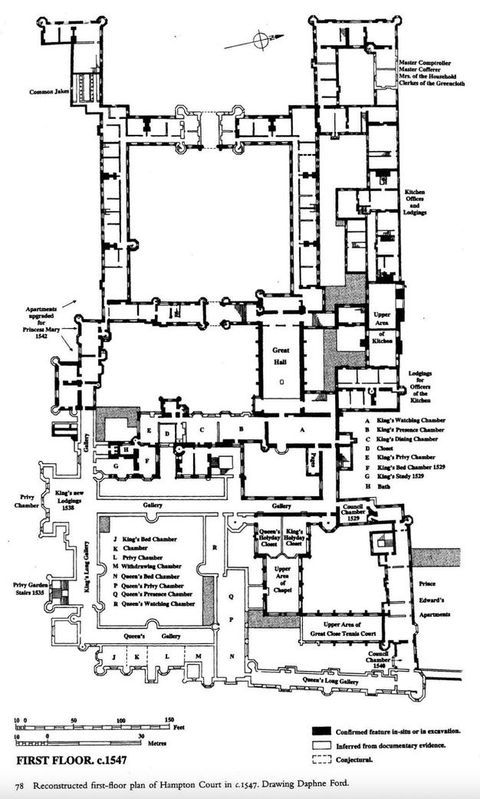

18Each palace chapel used by the late Tudor and early Stuart monarchs was furnished with a closet. These were typically located at the liturgical west of the building, facing the sanctuary at the east, and were connected to the royal apartments by a long gallery (fig. 1).20 After Henry VIII’s renovation of Whitehall, Hampton Court, St. James’s, and Greenwich palaces in the 1530s and 1540s, chapel closets followed a comparable architectural and spatial arrangement. This ensured that the monarch and their attendants were elevated above the courtly congregation, occupying a prominent place on the stage of this ecclesiastical space by the large glazed oriel window, which permitted congregants to catch a glimpse of their sovereign, and the elaborate facade of the closet itself. In addition to a communion table and prie-dieux, chapel closets were furnished with fireplaces, desks, and benches to accommodate the train of royal attendants and favourites.21 These were not small spaces and usually measured nearly half the length and width of the body of the court chapel, like that at St. James’s, which was twenty-four feet deep and twenty-seven feet wide (the chapel itself was seventy-nine feet long), and Hampton Court, which was forty feet deep and thirty-five feet wide (the chapel was sixty feet long).22 While court chapels were undoubtedly splendid in their architecture and decoration, chapel closets often matched and could even exceed the visual and material splendour of their adjacent chapels.

20

Chapel closets were not unique to England, and comparisons and precedents are found across the courts of early modern Europe. After the 1560s, and unlike his French, Spanish, and Danish counterparts, the Scottish monarch was not raised on a balcony or scaffold on the gospel side of the altar or at the west end of the chapel. Instead, they were placed on the same level as the other congregants, on a “very common” (as one German visitor famously observed) wooden seat.23 During services, the king remained in full view of both congregants and officiating ministers, inverting the more familiar dynamic of withheld visual and physical access enjoyed by Europe’s early modern monarchs.24 In 1583 the king’s seat and the pulpit in Holyrood chapel were reconstructed using the same wainscotting, at the cost of 100 merks (£66 13s. 4d.).25 While this was an impressive sum, it is significant that the monarch’s seat received the same elaboration as the pulpit, a telling indication of the relationship between clergy and Crown in the Scottish kirk, even within the royal household. The consort and her ladies-in-waiting occupied a raised “cheppell loft”, restored at Stirling in 1583 and located on the liturgical north side of the chapel.26 It is perhaps no surprise that James, a passionate advocate for the primacy of the king’s authority over his church, gladly embraced the spatial arrangement of English courtly worship. One of the major architectural endeavours ahead of his “Scottish progress” in 1617 was the installation of a “clossit” in Holyrood Palace chapel that was to be “richlie and weill decored as becomes the lykes to be”.27 With the imported advice of English master masons such as Nicholas Stone and Inigo Jones, James doubtless sought to revise the apparent decorative equality imposed by the kirk between the pulpit and the king’s seat.28

23The chapel closets of the English palaces were not the first James had experienced. Far earlier, and perhaps more significant in the formation of his approach to religious spaces at court, James had visited Kronborg Castle during the Christmas of 1589–90. After bad weather prevented his fourteen-year-old bride, Anna of Denmark, from reaching Scotland, James travelled to Norway to collect her. Further bad weather prevented James and Anna from crossing the North Sea, so they spent the winter with Anna’s brother, the recently crowned Christian IV, in Denmark. At Kronborg, James would probably have visited the recently renovated chapel, which had galleries on the north and south sides to accommodate the monarch and consort respectively, and finely carved stalls on the ground floor of the chapel for prominent courtiers and other members of the royal family.29 James was keen to gloss over the theological differences between the reformed Scottish kirk and the Danish Lutheran Church, reporting that, with the significant exceptions of predestination and “the real presence of the Sacrament, Images, and other like thinges”, the Danes were “conformable in all tharticles of Religion”.30 He was also likely to have been impressed by Christian’s confident and stylish presentation of his royal authority in court spaces, not least the chapel, where, apart from the presence of religious images, he may have found a style of royal presentation that accorded closely with his personal conception of the authority held by the royal office. James did not visit Christian IV’s Frederiksborg Castle, complete in 1617, which contained a chapel closet replete with an ornate fireplace, cushioned royal seats, a large marble table, silver altarpieces, and a fine series of artworks depicting religious scenes along the interior walls.31 However, Christian’s visits to England in 1606 and 1614 may in turn have influenced a reciprocal aesthetic exchange between the courts of two leading Protestant monarchs. James’s introduction of mannerist and Solomonic allusions to his chapel at Stirling may therefore have been the first indication of his European influences as to how an anointed monarch might decorate his courtly venues of worship, which were extrapolated and expanded to the chapel closet upon his accession to the English throne.32

29The chapel closet was not only a space in the royal court but also an institutional wing of the royal ecclesiastical household. The most prominent officer associated with this space was the clerk of the closet. The post had its origins in the reign of Henry VI, who appointed his clerk from the royal ministers responsible for the daily celebration of the mass and invested him with authority over the personal daily devotions of the monarch.33 By the sixteenth century, the clerkship remained a distinguished post in the king’s ecclesiastical household and was a means of affording individual churchmen greater prestige and access to the king. At the post-Reformation court, the clerk’s duties were to oversee the appropriate adornment and furnishing of the chapel closet, to receive and secure the “stuff” for it, and to personally assist the monarch in their attendance and observance of services in the chapel closet.34 The post attracted a meagre wage of no more than £4 per annum, in addition to a livery worth £4 13s. 4d.35 However, the clerkship has been regarded by scholars as “a crucial Stuart point of political contact” on the basis that the incumbent personally attended the king during services, which offered a high degree of royal intimacy and access not usually afforded to court servants.36

33Richard Neile, James’s only clerk of the closet, replaced Elizabeth’s last clerk, John Thornborough (clerk 1586–1603), who also held the deanship of York from 1589 and the see of Limerick from 1593 to 1603. Thornborough continued to advance in the Jacobean church, receiving the sees of Bristol (1603) and Worcester (1617), but his replacement at court signalled a clear shift in the royal will.37 Neile’s appointment to the clerkship has been associated with an effort led by Richard Bancroft, archbishop of Canterbury (1604–10), to surround the king with figures staunchly opposed to Presbyterian influence in the Church of England.38 Neile was also a prominent avant-garde conformist, who actively promoted the beautification of church space and, as bishop, patronised individual churchmen who shared his opinions.39 As clerk, Neile influenced the selection of preachers for the Lent preaching rota, which allowed certain churchmen to be earmarked for future preferment and provided him with the opportunity to promote certain political or theological perspectives from the royal pulpit.40

37The appointment of Lancelot Andrewes as dean of the Chapel Royal on Christmas Day, 1618, has been identified with an increased beautification of court chapels. Neile’s position as clerk, it has been conjectured, was a beneficial supplement to Andrewes’s programme of reform, which may have involved the installation of communion rails in the chapel at Whitehall and saw the installation of an elaborate new screen for the chapel closet at Greenwich.41 However, such perspectives do not take full account of James’s involvement in these changes, and his continued investment in the materials furnishings of court chapels and closets throughout his reign.

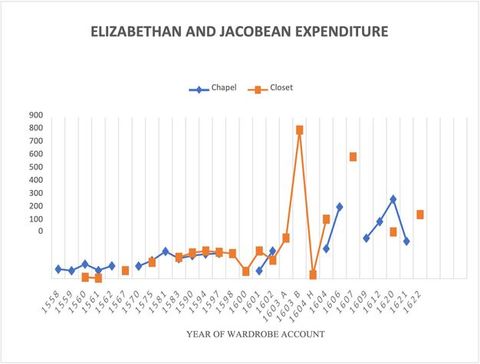

41Compared with Elizabeth’s average expenditure of some £300 every four years on fabrics and accoutrements for her chapel and closet together during the 1590s, James spent around £300 on his closet alone during more economical years, and some years, such as 1603 and 1607, saw heights of £829 17s. 8d. and £679 12s. 8d., respectively (fig. 2).42 While the presence of a royal family may have been one reason for the change, the materials purchased in each account appear to have furnished only the sovereign’s and the consort’s closets; separate accounts have survived for the prince’s closet from as early as 1604.43 While it is possible that Neile may have had some influence on James’s spending habits on ecclesiastical venues at court, the king’s first-hand experiences of the majesty of a leading European court and his personal investment in the material trappings of royal authority offer an equally plausible explanation for the increased strain the chapel and closet placed on the royal coffers. The appearance of religious venues at court could attract the ire of those who sought a more “reformed” example of public worship from their sovereign, and was doubtless influenced by the presence of avant-garde conformist churchmen in prominent courtly offices such as Neile and Andrewes. However, the furnishing of these spaces was also intimately linked to the monarch’s appreciation (or lack thereof) for household economy and the importance of suitably splendid material trappings in royal spaces. For James, the sovereign of multiple kingdoms and intimately aware of his need to reinforce the visual and material majesty of his enhanced status on a European stage, the court chapel and the chapel closet were important venues in which he might achieve this.

42

James’s accession to the English throne saw some significant changes to the role the chapel closet played in the ceremonial life of the English court. During Elizabeth’s reign, prominent noblemen and members of the bedchamber were permitted to hold wedding ceremonies and baptisms in the chapel closet.44 From James’s accession, this practice was suspended, and such ceremonies were held in the body of the chapel at a cost of £15 (£10 to the chapel dean and £5 to the subdean and gentlemen).45 Not only was this a rise from the two shillings required of Elizabethan noblemen, but it also limited wider access to the closet and demarcated the space as a more distinctly royal environment. James’s investment in the fabrics and furnishings of his closet was not then, in anticipation of a broader courtly ceremonial space, but rather to heighten an exclusively and distinctly royal venue of devotion and liturgical activity.

44Nonetheless, prominent influential Jacobean courtiers and noblemen could still access the closet, albeit under certain conditions. In January 1623 James issued a courtly ordinance to regulate the attendance of congregants in the stalls of royal chapels and during the procession to chapel services each Sunday and holy day.46 According to this ordinance, which was repeated in household ordinances throughout the 1620s and 1630s, noblemen and councillors were to occupy the north stalls (cantoris), and noblewomen the south stalls (decani). Regarding the closet, courtiers “under the degree of baron” were denied entry unless they were members of the Privy Council.47 This order was repeated in Caroline ordinances, and around 1630 it was expanded to include gentlemen of the bedchamber.48 In January 1617 Lady Anne Clifford recorded in her diary that when she visited Greenwich, expecting to find Queen Anna at chapel, she found the closet vacant and so heard the service taking place below from the closet, accompanied by a handful of other noblewomen.49

46It is unclear whether noble attendance in the closet was permitted during royal absences. The 1623 ordinance suggests that privy councillors, at least, were forbidden from doing so, since it specified that “when wee & the prince are absent … when any of the lords of o[u]r councell be belowe, o[u]r pleasure is, so much respect to be given to o[u]r councell (being o[u]r representative bodie) as th[a]t no man p[re]sume to be covered until they shall require them, so then only the sonnes of noble men, or such as serve us or the prince in eminent places”.50 Privy councillors were afforded the same level of honour when the king and prince were absent, but they do not appear to have been permitted to sit in the chapel closet, as indicated by their occupation of seats “belowe”.51 While the rules for non-royal attendance of the closet cannot be reconstructed with any greater specificity, this flexibility may have been part of an intentional policy that prioritised the monarch’s will and preference in inviting courtiers to join them during services. Given the importance of physical access to the monarch in the early modern court, it seems unlikely that all courtiers above the rank of baron would have equal opportunity to join James in his chapel closet. Instead, the rules of access to the closet appear to have depended in large part on the monarch’s consent and presence, thus heightening the potential for this intimate courtly space to be shaped according to the monarch’s personal preferences and political intentions.

50Foreign envoys and diplomats were regularly present in James’s chapel closet, as it offered a prominent opportunity for political interaction. Warming Anglo-European relations from 1603–4 onwards led to the re-establishment of many permanent embassies in London, and the chapel closet became a busy venue for international diplomacy. Foreign envoys were more rarely present in Elizabeth’s chapel closet, and usually in relation to precise marital or mercantile negotiations. Under James, annual services such as St. George’s Day, or major ceremonies of state like royal weddings, were good opportunities for diplomatic attendance, when the public stage of the closet could be used for a more personal and intimate mode of political diplomacy.52 Individual ambassadors are recorded as sitting in the closet during St. George’s services, but a group of ambassadors sat in the closet during Princess Elizabeth’s marriage to Elector Frederick of the Palatinate, indicating alternative provisions for major or extraordinary occasions.53 Unlike the court chapels of other European monarchs, no pew was specifically provided for ambassadors.54 The only official option available to visitors was to accompany the monarch on the consort’s side of the chapel closet, which both elevated the visibility of James’s ceremonial diplomacy and accorded ambassadorial visitors the honour due to the royal personages that they represented. This provision was a customary aspect of early modern diplomacy, and James’s enthusiastic expenditure on his closet could also be interpreted as part of his effort to enhance the material trappings of monarchy on a broader European stage, while staking England’s claim to primacy among the leading princely courts of Europe.

52Services of royal communion in the Chapel Royal were major occasions for the projection and construction of the monarch’s majesty and image as a divinely appointed governor of both church and state. These occasions were distinctly material, and their majesty was heightened by their occasional nature. On the major feast days of Easter, Christmas, and Whitsun (James also received communion on Maundy Thursday in 1610), nobles and leading courtiers were presented with the rare opportunity to see their sovereign receive the Eucharist in the sanctuary of the palace chapel, surrounded by richly vested ministers, fine cloths and cushions, and gilt plate.55 The fabrics necessary for the reception of communion were purchased for the chapel closet and transferred to the sanctuary of the court chapel ahead of major feast days. These were kept in the closet for most of the time, probably furnishing the communion table retained on the sovereign’s side.

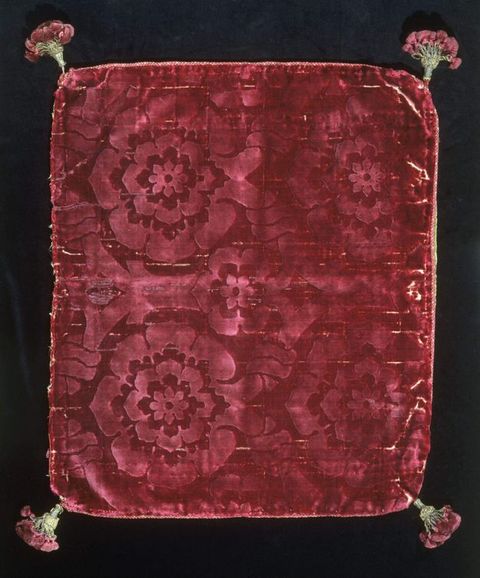

55Although no account survives of a communion service in the chapel closet, rich fabrics were purchased for its communion table on an annual basis. It was covered with a large pall of diaper (diamond-patterned) or holland (plain) cloth that matched the communion towels and usually had a frontal made of coloured velvet, taffeta, or cloth of gold, lined with red fustian cloth and fringed with gold and silver thread, sometimes with tassels.56 The communion table in the sanctuary of the chapel was comparatively bare and shared in the material splendour of the closet only during royal communion services, when it was furnished with a frontal. While the communion linens for both monarch and members of the royal household were of high quality, those purchased for the closet (and therefore royal use) were significantly richer in quality, and cost around £8 16s. each as purchased in 1607, while towels purchased for the chapel in 1609 cost £4 8s. 11d. each.57 Despite the inconsistency of individual prices, these items appear to have been of higher quality (and were certainly more expensive) than those purchased for the Elizabethan closet and the chapel, which cost £2 4s. 11d. for individual communion towels for the closet in 1583, and 10s. 4d. for towels used in the chapel, purchased in 1570.58 The materials purchased for the closet may have been made from richer fabric or included additional embellishment. Their effect was to heighten the exclusivity of the space of the chapel closet and the importance of the monarch and the royal family’s participation in a sacramental act, as distinct from that of the wider court and royal household.

56If James was a monarch who carefully controlled physical access to his person in his presence chamber and among his councillors, as work by Neil Cuddy and Jenny Wormald has demonstrated, the appearance and organisation of the chapel closet played an important part in the framing of his kingship.59 James’s financial investment in the furnishings of his chapel closet, which was significantly higher than his predecessor’s, reflected his appreciation of the material trappings expected of an imperial British monarch. While avant-garde conformists such as Neile enjoyed unparalleled access to the chapel closet, their influence is not readily distinguished from the alterations and innovations promoted by James himself, who had first-hand experience of what public worship at a leading European court looked and felt like and aimed to emulate and exceed it.

59Furnishing the Jacobean Closet

The appearance of chapel closets has not attracted as much scholarly attention as that of royal chapels. Court chapels could be venues of controversy and scandal because of the presence of offensive items such as a small gilt cross, which Elizabeth insisted on in the first decade of her reign, and the prominence of the courtly environment on major state occasions and holy days.60 The closet was accessible to only a select group of courtiers, attendants, and visitors, and records of their attendance include not details about what the closet looked like but, instead, descriptions of the service occurring in the main chapel, observed from above. Nevertheless, understanding what this space looked like is important not only for scholars of material culture, diplomacy, and royal devotion, but also for understanding the impact of James’s considerable financial investment in his courtly ecclesiastical venues.

60

Closets played an important role in the symbolic language of royal devotion and piety before and after the Reformation. The image of a monarch or member of the royal family kneeling in prayer on a prie-dieu or cushion in a small, enclosed, and richly furnished room has a long history in royal iconography, and it was adopted by Margaret Beaufort, Henry VIII, and Elizabeth I (figs. 3–5).61 There is no such surviving depiction of James I and VI except for a 1567 painting of him as a one-year-old, kneeling beside the tomb of his father (fig. 6).62 Before discussing the items purchased for the Jacobean closet in detail, it may be helpful to look at similar objects and their arrangement in near-contemporary depictions of similar spaces, even though they are highly stylised and intended to heighten the piety and majesty of the sitter.

61

Each depiction of early modern closet worship in England portrays a specific context, but they share certain similarities. The portraits that have survived are replete with royal and dynastic symbolism, usually in the fabrics that furnish and dominate the small spaces occupied by the monarch. In two portraits of royal women, Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth I, Tudor roses decorate the upper canopy and curtains, respectively, with addition of specific icons: the Beaufort portcullis adorns a wall tapestry behind Margaret, and fleurs-de-lys decorate the large carpet covering much of the prie-dieu on which Elizabeth kneels (figs. 3 and 5).63 Reality was far from the aim of such depictions, but the rich fabrics and designs are a plausible indication of some of the styles of royal and dynastic designs implemented in comparable courtly spaces. The depiction of Henry VIII on an illuminated page of the Black Book of the Garter (compiled between 1534 and 1551) represents the king at prayer in the “closet” above the Edward IV chantry chapel at Windsor, as indicated by the window tracery (fig. 4).64 No royal or dynastic imagery surrounds Henry, but the traverse (a square cloth structure in which monarchs knelt during communion services, comparable to the continental baldachin) is decorated with the royal motto “Dieu et mon droeit [sic]”. The illuminations of the Black Book of the Garter were not intended to be a naturalistic record of historical scenes but, instead, represented the arrangement and decoration of key moments in the Garter ceremonial for the use of royal servants and Garter officials. The depiction of Henry’s closet helps to establish the possible appearance of the chapel closet on principal feast days. While most depictions of monarchs at prayer in their closets or similar spaces were intended for a limited audience, or for functional use, that of Elizabeth, taken from the central plate of Richard Day’s Christian Prayers and Meditations, enjoyed widespread popularity and, though not coloured like the presentation copy held at Lambeth Palace Library, would have given Elizabethan and Jacobean readers an indication of what the interior of a chapel closet looked like.65 While access to chapel closets was limited, by the start of James’s English reign the appearance of the interior of chapel closets was known to a broader readership beyond the confines of court.

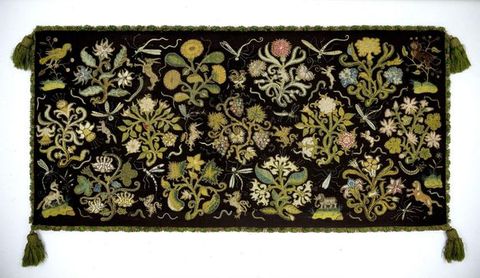

63Evidence of materials purchased for the chapel closet found in the auditors’ and Lord Chamberlain’s accounts for the Great Wardrobe confirm the kind of objects and materials shown in sixteenth-century depictions of chapel closets. Apart from wall hangings and a prie-dieu, tasselled cushions, communion table frontals, traverses, canopies, and devotional literature all appear among the items purchased for the closets of England’s last Tudor and early Stuart monarchs. This is not to say that fabrics did not cover the walls of Tudor or Stuart closets. Tapestries and hangings were probably supported by the 3,000–4,000 gilt hooks that regularly appear among the items purchased, for 13s. 4d. the dozen, alongside a mallet or hammer.66 Since hangings do not appear to have been purchased specifically for the closet, James probably drew on the vast reserves of arras and tapestries collected by his Tudor predecessors. This considerable collection included a wide range of symbolic, biblical, historical, mythological, and natural scenes, but the absence of evidence regarding their use in the closet precludes conjecture about their appearance.67

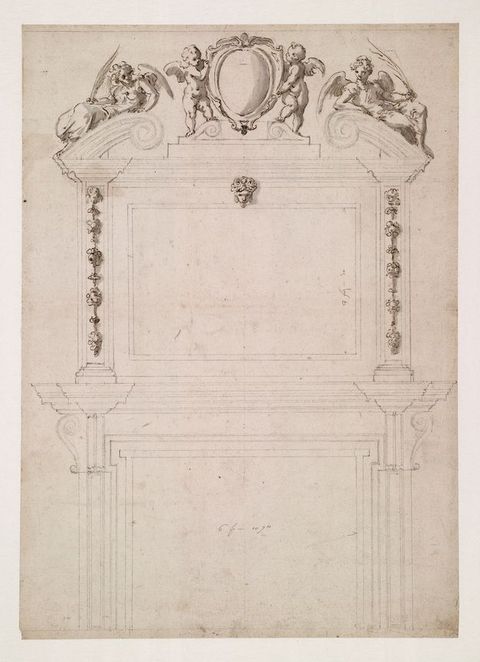

66Wall hangings would have gone some way to contributing to a physically warmer space, which was probably a key concern during the winter and spring months, when James’s court resided in palaces along the Thames. Most closets were furnished with fireplaces that were provided with a regular supply of fire-tending tools including fire-shovels (13s. 4d. each), tongs (2s. 6d. a pair), and leather pots (between 4d. and 3s. 4d. each).68 While we do not know what these items looked like, we know more about the fireplaces in closets from Inigo Jones’s design for a fireplace in the closet at the Queen’s Chapel of St. James’s Palace, constructed in 1623–25 (fig. 7). Steel perfuming pans also contributed to occupants’ sensory comfort by offsetting the odours of a cramped and poorly ventilated intimate space.69 While most of the functional items listed appear consistently through closet orders for the sixteenth century, Elizabeth did not purchase perfume pans specifically for her closet as James did. While this does not preclude their use in the Elizabethan closet, it further illustrates how James invested in the materials of his closet and made a particular effort to increase the comfort of its occupants.

68

Velvet cushions also provided physical comfort. Apart from a crimson cushion on which to rest the Book of Common Prayer during services, cushions for the monarch’s use do not appear in the surviving Elizabethan Wardrobe accounts, but they were not absent from worship. In a well-known account of the communion service held at Greenwich at Easter 1593, Elizabeth received the Eucharist while kneeling on a velvet cushion and was supported in her traverse by cushions set up on the epistle side of the sanctuary.70 This was the customary means of royal communion in the court chapel, and it is likely that a similar ceremony was observed in the closet. Given Elizabeth’s appreciation for household economy, the cushions used in her chapel and closet were possibly borrowed from another household department, serving the flexible requirements of a single royal household.

70From James’s accession, new cushions were purchased for the specific use of the chapel closet. These items were elaborate and expensive. A purple velvet cushion with a gold fringe and crimson silk tassels, and with gold and silver embroidery on the cover, was purchased for Prince Henry’s closet in 1604 for £8.71 In 1607 four long cushions and two short ones, both of cloth of gold, lined with velvet, and fringed and tasselled with gold and silk, were purchased for the sovereign’s and consort’s closets, costing £78 6s. 9d. in total, alongside a further three crimson velvet cushions for both the sovereign’s and the consort’s sides at a cost of £22 18s.72 James spared no expense on the furnishings of his closet. Orders for multiple cushions of various sizes survive in almost all the surviving Wardrobe accounts for the Jacobean closet (1604, 1605, 1607, 1620, and 1622).73 It is difficult to recover a clear decorative scheme from the descriptions of the cushions in the Wardrobe accounts alone, but they may have been designed to match the decoration of the cloth of gold, crimson, and purple frontals and the palls purchased for the communion table in the closet.74 The appearance of these items is suggested by a small number of surviving velvet cushion covers from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries held in the Victoria and Albert Museum, which also have the same red fustian lining recorded on the cushions in James’s closet (figs. 8 and 9). By having them made of fabrics reserved for use only in the closet, and by exercising considerable control over the colour scheme (primarily Stuart red and yellow, or gold) and the quality of the furnishings, James enhanced the prestige of the space.

71From his accession, James sought to improve the quality of the furnishings of Elizabeth’s closet. For example, in 1604 he purchased three frontals for the closet communion table at Whitehall at £249 14s. 1d. each.75 Each frontal cost around £150 more than the most expensive frontals purchased by Elizabeth (in 1597) and was made of purple and crimson velvet, with red fustian lining, and gold and silver silk embroidery.76 Frontals were the most expensive item recorded in the closet accounts during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, partly because of their size but also because they were transferred to the communion table in the sanctuary of the chapel for major holy days and state occasions. It is likely that James wanted to make a good impression on his English subjects, and the value of the frontals purchased for his closet (and therefore chapel) gradually decreased over the course of his reign; in 1607, for example, four frontals were purchased for £60 7s. 10d. each.77 This was still a considerable sum; it matched the price of frontals purchased by Elizabeth during the 1590s and was just over £7 less than the most expensive frontal purchased by Elizabeth, in 1594.78 However, a lower price did not necessarily mean a diminution in magnificence. These frontals were much more expensive than those used in aristocratic households; for example, a frontal at the Vyne chapel in 1541 was valued at £8.79 What is to be made, then, of these fluctuations in the price of an expensive investment that was deemed necessary for the performance of royal worship? James’s initial investment in frontals may reflect a monarch anxious not only to amplify the visual and material majesty of his court but also to show that he was enthusiastic about the performance of the ceremonies of the Book of Common Prayer, and their potential trappings.

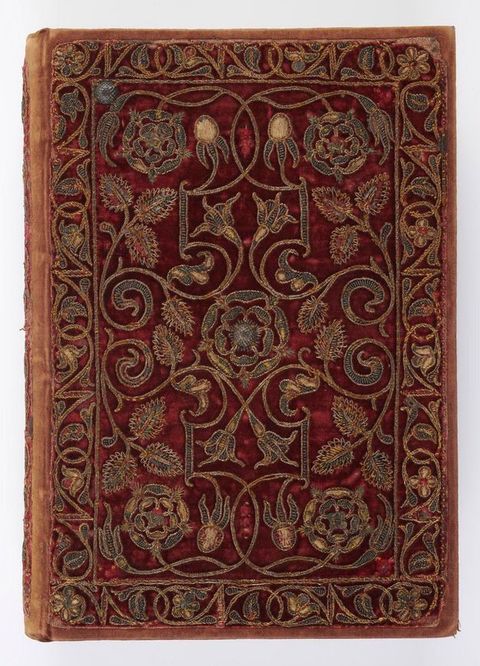

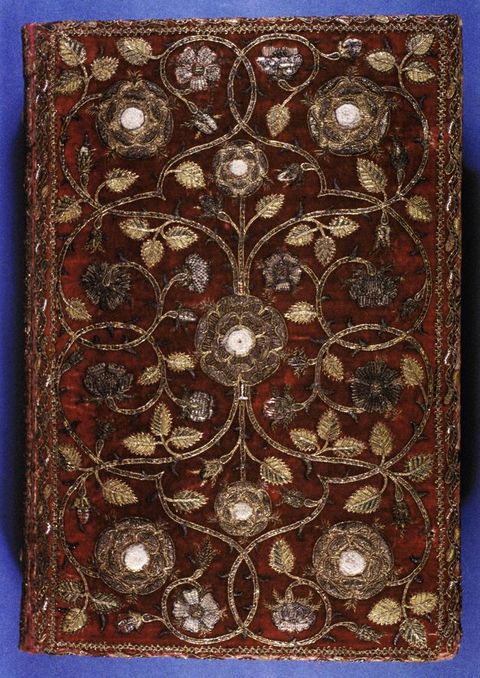

75Devotional literature was a key aspect of the chapel closet, and James, as theologian-king, eagerly indulged his bibliographic habits in this semi-visible space of royal piety. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign, the books typically purchased for the chapel closet were two folio Bibles, a smaller Bible (probably used by the monarch), and twenty-four service books. James continued this pattern of purchase. However, he also invested in two Bibles with gold and silver clasps, embroidery, and gilt plates on either side, which were purchased along with a service book for £32 19s. 8d. in 1622.80 While some of the Bibles and service books purchased for Elizabeth’s closet also had velvet covers and gilt decorations, none of them rivalled these expensive items. These books may have been purchased for specific state events like the anticipated marriage between Prince Charles and Infanta Maria Ana of Spain, the articles of which were solemnised at Whitehall in 1623, though negotiations had collapsed by the autumn of the same year. Two similarly elaborate Bibles were purchased for James and Anna in 1607 at £33 0s. 4d., conceivably in connection with the birth or death of Princess Sophia.81 These items were significantly more expensive than the variously sized Bibles purchased for liturgical use, which ranged between £5 and £9. A couple of embroidered velvet-bound presentation Geneva Bibles that have survived from Elizabeth’s reign, dated to 1577 and 1583, may give an idea of what these Bibles could have looked like (figs. 10 and 11). It is plausible that James’s arms, like Elizabeth’s, were integrated into the decoration of Bibles used in the royal closet. More Bibles and service books with velvet covers have been recorded for James’s closet than Elizabeth’s, indicating both Elizabeth’s sense of economy and the requirements of more royal bodies in the royal closet, all of whom required suitably decorous books to aid their worship. James’s investment in elaborate books for exclusive use in the closet highlights how he made a greater effort than Elizabeth had to provide his closet with its own “stuff”. He recognised the political potential of devotional material that was used in the intimate setting of his chapel closet.

80

Certain books were used in the chapel closet that had a personal association with James beyond their function as a liturgical aid. The most prominent of these was the 1611 translation of the Bible, which James had patronised. This translation may have appeared in the chapel closet as early as 1612, when three Bibles (versions unspecified), along with four communion books and thirty-three psalters were purchased for a total of £23 18s. 9d.82 Although James’s relationship with what we now know as the “King James Version” was complex, it is probable that this translation was used at court in the years following its publication.83 The presence of the fruit of this royal translation project, elaborately decorated and physically held by its royal commissioner, would probably have emphasised James’s image as patron and theologian-king, and helped to emphasise his erudition and theological weight as a Protestant monarch in a semi-public environment. The only non-liturgical book recorded in the Jacobean Wardrobe accounts for the chapel closet is also significant. In 1605 two volumes of the “book of Cronicles of the best making” were purchased for £6.84 It is unclear what book was purchased on this occasion, but the two volumes were probably a historical chronicle, possibly of England, Scotland, or Ireland; the best-known British “chronicle”, that by Raphael Holinshed, was first published as two volumes in 1577 and expanded to three in 1587.85 Such a book would have lent force to James’s “Union” project, but how it might have been used during sermons and services is not known. Alternatively, but less likely, the book may have been an extraordinarily expensive and separately printed edition of the first and second books of Chronicles, which trace the line of Judah from Adam and David, and provided a narrative of the reigns of David and Solomon. These books would have accorded with James’s conscious emulation of these biblical kings and had regular liturgical use by him, but there is no record of such an edition.86 Whatever the case may have been, James was clearly willing to spend considerable sums of money on the books in his closet, outstripping his predecessor’s investment and contributing to a distinct bibliophilic culture in his chapel closet.

82James had a different attitude to the appearance and organisation of his chapel closet from Elizabeth. While many of the items purchased for his own and his family’s use were similar, only more expensive and more plentiful, he also ensured that key accoutrements such as cushions and Bibles were for the specific and likely exclusive use of his chapel closet. The reasons for this may have been that he had a royal family, which meant more regular use of both the sovereign’s and consort’s sides of the closet, and his different approach to the finances of the royal household. These shifts in organisation had important consequences for how James presented himself in courtly worship.87 Investment in certain materials or items to emphasise an iconographic or dynastic message was a feature common to most, if not all, early modern monarchies. James expanded the materials for his closet to ensure that the space was suitably decorated for both ferial and festal occasions, and to ensure the physical comfort of his family. After hearing services in their respective households, members of the royal family would join him in the Chapel Royal each Sunday, filling the material frame of the closet with a picture of the Stuart progeny and dynastic security, in contrast to the image of a single queen projected by Elizabeth I. James’s ability to utilise courtly space and furnishings was closely connected to his willingness to spend from the royal purse and invest in prominent spaces in the religious and ceremonial life of the early Stuart court.

87Conclusion

James changed the way the chapel closet was used in the English court compared with the example set by his Tudor predecessor. In addition to making the closet a more distinctly royal venue, where the monarch and royal family, rather than leading members of the English court, were the principal liturgical actors and guests, James poured greater sums of money into purchasing materials for this intimate ecclesiastical space. These changes did not take place gradually over the course of his English reign but were implemented soon after his accession to the throne. As a political actor, James preferred intimate spaces where attendance, visibility, and furnishing could be controlled, and the closet provided an ideal venue for his style of kingship. The English chapel closet was the first of such venues that he, as king, had control over, and he was able to make use of English ceremonial modes or to break them as he saw fit. Since he had not grown up with the chapel closet as a regular feature of court life, he may also have drawn from Danish models he knew at first hand to inform his pattern of investment. As an imperial British monarch, James recognised the need to furnish his main palaces of residence (those along the Thames) in a suitable manner, in his ambition to see the Stuart kingdoms ranked alongside those of the French Valois or of the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs.

The Jacobean chapel closet was a prominent political, religious, and symbolic space. It provided the institutional base for prominent avant-garde conformists such as Richard Neile, offered a venue for diplomatic interaction, and enshrined an anointed monarch in the material trappings of the royal office during regular semi-public religious ceremonies. The furnishings of the closet may have been selected by Neile, but this does not mean that the venue should be seen as an exclusively avant-garde conformist space, since James himself was not an avant-garde conformist. Rather, the material furnishings found in the chapel closet were an essential part of his construction of his image as a modern Protestant monarch, performed in a spatially and politically intimate venue for a select group of courtiers, noblemen, and foreign visitors. The success of this performance is the subject of another study. However, this article has illustrated how James utilised the material culture of English ceremonial to delineate and control courtly space according to his preferred style of personal political interaction.

From the perspective of those in the stalls of court chapels, James was literally framed by the material majesty that was essential to his royal image. The building and much of the decor in royal palaces may have been commissioned by his Tudor predecessors, but James would have been visible in the closet window with his consort, Anna, next to him and possibly the royal children, against a backdrop of material splendour hung from the closet walls and furnishing lecterns, seats, benches, and communion tables, all of which outstripped those of his predecessor, at least in terms of cost and likely appearance. James’s largesse on his royal closets emphasised both the necessary realities of a growing Stuart dynasty and his desire to heighten the prestige and sensation of religious ceremonial at the English court.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, Catriona Murray, Alixe Bovey, Baillie Card, and the three anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful comments in shaping this article. I also thank Antonio Pattori for reading an early draft of this piece and Harry Spillane for his expert advice. Any remaining errors are my own.

About the author

-

Oscar Patton is a historian of early modern British religion, society, and culture, with a particular interest in music-making, confessional identities, and liturgical performance within ecclesiastical institutions. His doctoral thesis examined the Elizabethan and Jacobean Chapel Royal, and he is currently developing this into a monograph that will also look at the reign of Charles I. He is also co-editing a British Academy Proceedings volume, provisionally titled “Music and Majesty in English Chapels Royal and Extraordinary Spaces, c.1560–1700”, and working on a postdoctoral project on the liturgical staff of English and Welsh cathedrals between 1558 and 1642. He completed a doctorate in history at Merton College, Oxford (2025), an MSt in early modern history at Jesus College, Oxford (2021), and a BA in history at the University of York (2020).

Footnotes

-

1

The first part of this article’s title is adapted from a narrative of the 1605 christening of Princess Mary, held at Greenwich: “his Majestie (with the Prince) in his clossett above”. The Cheque Books of the Chapel Royal, with Additional Material from the Manuscripts of William Lovegrove and Marmaduke Alford, vol. 1, ed. Andrew Ashbee and John Harley (Farnham: Ashgate, 2000), 94. ↩︎

-

2

Peter McCullough, Sermons at Court: Politics and Religion in Elizabethan and Jacobean Preaching (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 16. ↩︎

-

3

Simon Thurley, Whitehall Palace: An Architectural History of the Royal Apartments, 1240–1689 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 48; Lena Cowen Orlin, Locating Privacy in Tudor London (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 3. ↩︎

-

4

Fiona Kisby, “‘When the King Goeth a Procession’: Chapel Ceremonies and Services, the Ritual Year, and Religious Reforms at the Early Tudor Court, 1485–1547”, Journal of British Studies 40, no. 1 (2001): 53. ↩︎

-

5

Simon Thurley, The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: Architecture and Court Life, 1460–1547 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 125–27. ↩︎

-

6

Where other works on the subject have used “royal closet” or “holyday closet” to describe the raised space adjoining court chapels, this article prefers “chapel closet” as a more direct alternative, since the privy closet was also “royal”, and the chapel closet was not necessarily used just on holy days. For a contemporary use of the phrase “chapel closet”, on the occasion of the 1622 Garter service, see John Finett, Finetti Philoxenis: Som Choice Observations of Sr. John Finett knight, and Master of the Ceremonies to the Two Last Kings, Touching the Reception, and Precedence, the Treatment and Audience the Puntillios and Contests of Forren Ambassadors in England (London, 1656), 106. ↩︎

-

7

Simon Thurley, “The Politics of Court Space in Early Stuart London”, in The Politics of Space: European Courts, ca. 1500–1750, ed. Marcello Fantoni, George Gorse, and Malcolm Smuts (Rome: Bulzoni, 2009), 293–316. ↩︎

-

8

For a discussion of Neile’s influence over the Lent preaching rota as clerk, see McCullough, Sermons at Court, 110–16; Andrew Foster, “Archbishop Richard Neile Revisited”, in Conformity and Orthodoxy in the English Church, c.1560–1660, ed. Peter Lake and Michael C. Questier (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000), 162–63. ↩︎

-

9

Peter Lake, “Lancelot Andrewes, John Buckeridge, and Avant-Garde Conformity at the Court of James I”, in The Mental World of the Jacobean Court, ed. Linda Levy Peck (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 133. For a full discussion of the history and meaning of the term, see Peter McCullough, “‘Avant-Garde Conformity’, in the 1590s”, in The Oxford History of Anglicanism, vol. 1, Reformation and Identity, c.1520–1662, ed. Anthony Milton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 380–94. ↩︎

-

10

Andrew Foster, “Neile, Richard (1562–1640)”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2008), DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/19861. ↩︎

-

11

See John Adamson, “Introduction: The Making of the Ancien-Regime Court 1500–1750”, in The Princely Courts of Europe: Ritual, Politics and Culture under the Ancien Regime, 1500–1750, ed. John Adamson (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999), 24–32. ↩︎

-

12

The symbolic significance of this arrangement is discussed in McCullough, Sermons at Court, 25, 30, 40. ↩︎

-

13

For a clear discussion of this, see David Starkey, “Introduction: Court History in Perspective”, in The English Court: From the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War, ed. David Starkey (London: Longman, 1987), 8–9. ↩︎

-

14

See Jenny Wormald, “James VI and I: Two Kings or One?”, History 68, no. 228 (1983): 197; David Coast, News and Rumour in Jacobean England: Information, Court Politics and Diplomacy, 1618–25 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 5. ↩︎

-

15

For further discussion of the impact of this on the government of James’s early Chapel Royal, see McCullough, Sermons at Court, 107–8. ↩︎

-

16

The History of the King’s Works, vol. 1, The Middle Ages, ed. R. Allen Brown, H. M. Colvin, and A. J. Taylor (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1963), 124. ↩︎

-

17

Thurley, The Royal Palaces of Tudor England, 197. ↩︎

-

18

The chapel closet is sometimes described as the “larario” in the auditors’ accounts of the Great Wardrobe. This was likely a Ciceronian substitute for “closet”, referring to the spaces of Roman houses where the household gods were worshipped. It emphasises the separate liturgical use of the chapel closet from that of the court chapel. See Great Wardrobe, Yearly Accounts, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, LC 9/82 (1590–91), fol. 5r; LC 9/86 (1594–95), fol. 5v; Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, Audit Office Accounts, TNA, AO 1/2343/25 (1597–98); AO 1/2344/30 (1602–3); AO 1/2344/31 (1603–4); AO 1/2344/32 (1604–5); AO 1/2348/48 (1620–21). See “lararium” in Charlton T. Lewis et al., A Latin Dictionary Founded on Andrews’ Edition of Freund’s Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), 1036. ↩︎

-

19

“A Collection of Original Warrants and Other Documents”, British Library (BL), London, Add MS 5750, fols. 38r–43r. ↩︎

-

20

The only exception to this among the royal palaces close to London was Richmond, where Henry VII’s traditional placement of the sovereign’s and consort’s closets on the south and north sides, respectively, was maintained throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Each closet was accessed by passageways that ran parallel to the body of the chapel. H. M. Colvin, The History of the King’s Works, vol. 4 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1982), 225. ↩︎

-

21

Lisa Monnas, “The Splendour of Royal Worship”, in The Inventory of King Henry VIII, vol. 2, Textiles and Dress, ed. Maria Hayward and Philip Ward (London: Harvey Miller, 2012), 297. ↩︎

-

22

William Dickinson, Survey Plan of the Palace, circa 1703–14, All Souls College, 250–AS I.2, https://library.asc.ox.ac.uk/wren/st_james_palace.html; Peter Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England, 1549–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 75–77. ↩︎

-

23

Gottfried von Bulow, “Journey through England and Scotland made by Lupold von Wedel in the Years 1584 and 1585”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 9 (1895): 245. ↩︎

-

24

In Spain, for instance, the monarch remained entirely obscured to congregants while seated in his cortina, a cloth structure positioned on the north side of the sanctuary, facing liturgical east, apart from Good Friday, when he took communion publicly before the altar. Etiquetas Generales (1647–51), Historical Section, Box 51, File 1, fol. 186r, Archivo General de Palacio, Madrid, cited in Juliet Glass, “The Royal Chapel of the Alcázar: Princely Spectacle in the Spanish Habsburg Court” (PhD thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2004), 207. ↩︎

-

25

John Imrie and John G. Dunbar, ed., Accounts of the Masters of Works, vol. 1 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1957), 312. ↩︎

-

26

Imrie and Dunbar, Accounts of the Masters of Works, 1:311. ↩︎

-

27

John Imrie and John G. Dunbar, ed., Accounts of the Masters of Works, vol. 2 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1982), 441. ↩︎

-

28

James Sherrington Jago, “The Dissemination and Reassessment of Private Religious Spaces in Early Modern England, 1600–1660: An Examination of the Cultural Contexts surrounding Royal, Episcopal & Collegiate Chapels from the Accession of James I to the Restoration” (PhD thesis, University of York, 2012), 101–5. ↩︎

-

29

Hugo Johannsen, “The Protestant Palace Chapel: Monument to Evangelical Religion and Sacred Rulership”, in Signs of Change: Transformations of Christian Traditions and Their Representation in the Arts, 1000–2000, ed. Nils Holger Petersen, Claus Clüver, and Nicholas Bell (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2004), 149–50. ↩︎

-

30

Letter from Robert Bowes to Burghley, 24 April 1590, TNA, SP 52/45, fol. 34v. ↩︎

-

31

Hugo Johannsen, “Christian IV’s Private Oratory in Frederiksborg Castle Chapel—Reconstruction and Interpretation”, in Pieter Isaacsz (1568–1625): Court Painter, Art Dealer and Spy, ed. Badeloch Noldus and Juliette Roding (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), 167–70. For further discussion of Christian IV’s architectural investment, see Joakim A. Skovgaard, A King’s Architecture: Christian IV and His Buildings (London: Hugh Evelyn, 1973). ↩︎

-

32

Ian Campbell and Aonghus Mackechnie, “The ‘Great Temple of Solomon’ at Stirling Castle”, Architectural History 54 (2011): 91–118. ↩︎

-

33

John Bickersteth and Robert W. Dunning, Clerks of the Closet in the Royal Household: Five Hundred Years of Service to the Crown (Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1991), 3. ↩︎

-

34

Bickersteth and Dunning, Clerks of the Closet in the Royal Household, 7. ↩︎

-

35

“Accounts of Sir Thomas Heneage, Treasurer of the Queen’s Chamber, Michaelmas 1581–1582”, BL, Harley MS 1644, fol. 6r; Great Wardrobe, TNA, LC 9/78 (1586–87), fol. 46v. ↩︎

-

36

McCullough, Sermons at Court, 110. ↩︎

-

37

Brett Usher, “Thornborough, John (1551?–1641)”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online (Oxford University Press, 2013), DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/27339. ↩︎

-

38

McCullough, Sermons at Court, 106–13. ↩︎

-

39

Andrew Foster, “A Biography of Archbishop Richard Neile (1563–1640)” (DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 1978), 155. ↩︎

-

40

McCullough, Sermons at Court, 111. ↩︎

-

41

Nicholas Tyacke, “Lancelot Andrewes and the Myth of Anglicanism”, in Conformity and Orthodoxy in the English Church, c.1560–1650, ed. Peter Lake and Michael Questier (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000), 31–32. ↩︎

-

42

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/31 (1603–4); TNA, AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8). ↩︎

-

43

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5). ↩︎

-

44

The Cheque Books of the Chapel Royal, with Additional Material from the Manuscripts of William Lovegrove and Marmaduke Alford, vol. 1, ed. Andrew Ashbee and John Harley (Ashgate, 2000), 171. ↩︎

-

45

Cheque Books of the Chapel Royal, 178. ↩︎

-

46

Dates in this article are provided in the Gregorian form, with each new year beginning on 1 January. At this time England officially began each new year on 25 March, until 1752, when the Julian calendar was dropped and the Gregorian adopted. ↩︎

-

47

“Collection of political and other papers made by Sir Julius Caesar, Chancelor of the Exchequer, Master of the Rolls, etc. consisting of transcripts of state papers, and various political and legal rules, together with a few private letters”, BL, Add MS 34324 fol. 215r; “Orders sett downe by his Ma[jes]ty for Civility in sittinges eyther in the Cappell or elsewhere in Court primo Januarii 1622”, BL, Lansdowne MS 125, fol. 33v. ↩︎

-

48

“Ordinances of the king’s household in the time of James I”, BL, Lansdowne MS 246 fol. 5v. ↩︎

-

49

The Diary of Lady Anne Clifford, ed. Vita Sackville-West (London: Westminster Press, 1923), 49. ↩︎

-

50

“Collection of Political and Other Papers”, BL, Add MS 34324, fol. 215v. See also Household regulations—Charles I, circa 1630, TNA, LC 5/180. ↩︎

-

51

The honour here was an exception to canon 18 of the 1604 canons, which ordered that all congregants remain uncovered on entering churches or chapels. See Arnold Hunt, Protestant Bodies: Gesture in the English Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024), 248–50. ↩︎

-

52

John Finett, Finetti Philoxenis: Som Choice Observations of Sr. John Finett knight, and Master of the Ceremonies to the Two Last Kings, Touching the Reception, and Precedence, the Treatment and Audience the Puntillios and Contests of Forren Ambassadors in England (London, 1656), 25, 34, 79, 106–8. ↩︎

-

53

Finetti Philoxenis, 13. ↩︎

-

54

See Etiquetas Generales (1647–51), Box 51, File 1, fol. 186r, cited in Glass, “The Royal Chapel of the Alcázar”, 207; “L’Ordre que le Roy veut ester tenu par son gran ausmosnier”, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris, F-Pn MS nouv. Acq. Fr. 9740, cited in Peter Bennett, Music and Power at the Court of Louis XIII: Sounding the Liturgy in Early Modern France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 114. ↩︎

-

55

Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, vol. 11, 1607–1610, ed. Horatio F. Brown (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1904), no. 858; “Parliamentary diary of Sir Robert Paulet, 1610–11”, Hertfordshire Record Office, Jervoise MSS 44MGA/F6, fol. 6r. ↩︎

-

56

See the Wardrobe accounts for 1604 and 1620: Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5); “Collection of Original Warrants”, BL, Add MS 5750, fol. 43r; AO 1/2348/48 (1620–21). ↩︎

-

57

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8); AO 1/2346/38 (1608–9). ↩︎

-

58

Great Wardrobe, TNA, LC 9/75 (1583–84), fol. 15v; LC 9/62 (1570–71), fol. 5r. ↩︎

-

59

Neil Cuddy, “The Revival of the Entourage: The Bedchamber of James I, 1603–1625”, in The English Court, ed. Starkey, 173; Wormald, “Two Kings or One?”, 188–89. ↩︎

-

60

See Margaret Aston, The King’s Bedpost: Reformation and Iconography in a Tudor Group Portrait (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 101–7; Oscar Patton, “Majesty and Music in Royal Worship: The English Chapel Royal, 1558–1625”, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 76, no. 3 (2025): 570–72. ↩︎

-

61

The famous depiction of Charles I from the frontispiece of Eikon Basilike is not discussed here because the king is depicted in a church, not a closet. ↩︎

-

62

Livinus de Vogelaare, The Memorial of Lord Darnley, 1567, Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/401230/the-memorial-of-lord-darnley. ↩︎

-

63

Meynart Weywyck, “Portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby”, c.1510 St John’s College, Cambridge; Richard Day, Christian Prayers and Meditations in English, French, Italian, Spanish, Greeke, and Latine (London, 1569), sig. 2v, Lambeth Palace Library. ↩︎

-

64

“Black Book” of the Garter, St. George’s College Archives, G.1; Roy Strong, The English Renaissance Miniature (London: Thames & Hudson, 1984), 40–41. ↩︎

-

65

Linda Shenk, Learned Queen: The Image of Elizabeth I in Politics and Poetry (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 21. ↩︎

-

66

Great Wardrobe, TNA, LC 9/67 (1575–76), fol. 7v; “Collection of Original Warrants”, BL, Add 5750, fols. 39r, 40r, 43r. ↩︎

-

67

For a discussion of the Tudor tapestry collection, see Thomas P. Campbell, Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty: Tapestries at the Tudor Court (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007). ↩︎

-

68

Great Wardrobe, TNA, LC 9/95 (1606–7), fol. 31v; Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5); AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8). ↩︎

-

69

In the absence of surviving records detailing the scents used in the closet perfuming pan, it is difficult to conjecture what James’s closet might have smelled like. He may have continued his predecessor’s predilection for orris powder and rosewater or may have sought to establish a new olfactory culture on his accession. Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5); AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8); AO 1/2348/48 (1620–21); Holly Dugan, “Scent”, in Early Modern Court Culture, ed. Erin Griffey (Abingdon: Routledge, 2022), 433. ↩︎

-

70

The Cheque Books, 1:55. ↩︎

-

71

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5). ↩︎

-

72

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8). ↩︎

-

73

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5); “Collection of Original Warrants”, BL, Add 5750, fol. 42r; TNA, AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8); AO 1/2348/48 (1620–21); TNA, AO 1/2349/53 (1622–23). ↩︎

-

74

A similar scheme was observed in Henry VIII’s closet. See Monnas, “The Splendour of Royal Worship”, 299. ↩︎

-

75

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/31 (1603–4). ↩︎

-

76

Great Wardrobe, TNA, LC 9/88 (1597–98), fol. 10r. ↩︎

-

77

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8). ↩︎

-

78

Great Wardrobe, TNA, LC 9/82 (1590–91), fol. 5r; LC 9/86 (1594–95), fol. 5v; LC 9/88 (1597–98), fol. 9v; Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2343/25 (1597–98). ↩︎

-

79

Annabel Ricketts, The English Country House Chapel: Building a Protestant Tradition (Reading: Spire Books, 2007), 83. According to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, this would have been closer to £22 in 1600. “Inflation Calculator”, Monetary Policy, Bank of England, accessed 10 December 2025, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator. ↩︎

-

80

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2349/53 (1622–23). ↩︎

-

81

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8). ↩︎

-

82

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2349/53. ↩︎

-

83

Kenneth Fincham, “The King James Bible: Crown, Church and People”, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 71, no. 2 (2020): 77–97. ↩︎

-

84

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, TNA, AO 1/2345/31 (1603–4); “Collection of Warrants”, BL, Add MS 5750, fol. 42r. ↩︎

-

85

Raphael Holinshed, The Firste Volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande (London, 1577). ↩︎

-

86

My thanks to Harry Spillane for his advice on this point. ↩︎

-

87

For an examination of James’s approach to household finances, see P. R. Seddon, “Household Reforms in the Reign of James I”, Historical Research 53, no. 127 (1980): 44–55. ↩︎

Bibliography

Manuscript Sources

“Accounts of Sir Thomas Heneage, Treasurer of the Queen’s Chamber, Michaelmas 1581–1582”. Harley MS 1644. British Library, London.

Black Book of the Garter. G.1. College of St. George Archives, Windsor.

Letter from Robert Bowes to Burghley, 24 April 1590. SP 52/45. The National Archives, Kew.

“A Collection of Original Warrants and Other Documents”. Add MS 5750. British Library, London.

“Collection of political and other papers made by Sir Julius Caesar, Chancelor of the Exchequer, Master of the Rolls, etc. consisting of transcripts of state papers, and various political and legal rules, together with a few private letters”. Add MS 34324. British Library, London.

Etiquetas Generales (1647–51). Historical Section, Box 51, File 1. Archivo General de Palacio, Madrid.

Great Wardrobe, Yearly Accounts. LC 9/62 (1570–71); LC 9/67 (1575–76); LC 9/75 (1583–84); LC 9/78 (1586–87); LC 9/82 (1590–91); LC 9/86 (1594–95); LC 9/88 (1597–98); LC 9/95 (1606–7). The National Archives, Kew.

Household regulations—Charles I, c.1630. LC 5/180. The National Archives, Kew.

Masters or Keepers of the Great Wardrobe, Audit Office Accounts. AO 1/2341/13 (1583–84); AO 1/2343/25 (1597–98); AO 1/2344/30 (1602–3); AO 1/2344/31 (1603–4); AO 1/2344/32 (1604–5); AO 1/2345/31 (1603–4); AO 1/2345/32 (1604–5); AO 1/2345/35 (1607–8); AO 1/2346/38 (1608–9); AO 1/2348/48 (1620–21); AO 1/2349/53 (1622–23). The National Archives, Kew.

“L’Ordre que le Roy veut ester tenu par son gran ausmosnier”. F-Pn MS nouv. Acq. Fr. 9740. Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris.

“Orders sett downe by his Ma[jes]ty for Civility in sittinges eyther in the Cappell or elsewhere in Court primo Januarii 1622”. Lansdowne MS 125. British Library, London.

“Ordinances of the king’s household in the time of James I”. Lansdowne MS 246. British Library, London.

“Parliamentary diary of Sir Robert Paulet, 1610–11”. Jervoise MSS 44MGA/F6. Hertfordshire Record Office.

Printed Sources

Adamson, John. “Introduction: The Making of the Ancien-Regime Court 1500–1750”. In The Princely Courts of Europe: Ritual, Politics and Culture under the Ancien Regime, 1500–1750, edited by John Adamson, 7–41. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999.

Aston, Margaret. The King’s Bedpost: Reformation and Iconography in a Tudor Group Portrait. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Bennett, Peter. Music and Power at the Court of Louis XIII: Sounding the Liturgy in Early Modern France. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Bickersteth, John, and Robert W. Dunning. Clerks of the Closet in the Royal Household: Five Hundred Years of Service to the Crown. Stroud: Alan Sutton, 1991.

Bulow, Gottfried von. “Journey through England and Scotland Made by Lupold von Wedel in the Years 1584 and 1585”. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 9 (1895): 223–70.

Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice. Vol. 11, 1607–1610. Edited by Horatio F. Brown. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1904.

Campbell, Ian, and Aonghus Mackechnie. “The ‘Great Temple of Solomon’ at Stirling Castle”. Architectural History 54 (2011): 91–118.

Campbell, Thomas P. Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty: Tapestries at the Tudor Court. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007.

The Cheque Books of the Chapel Royal, with Additional Material from the Manuscripts of William Lovegrove and Marmaduke Alford. Vol. 1. Edited by Andrew Ashbee and John Harley. Farnham: Ashgate, 2000.

Clifford, Lady Anne. The Diary of Lady Anne Clifford. Edited by Vita Sackville-West. London: Westminster Press, 1923.

Coast, David. News and Rumour in Jacobean England: Information, Court Politics and Diplomacy, 1618–25. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014.

Colvin, H. M. The History of the King’s Works. Vol. 4. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1982.

Cowen Orlin, Lena. Locating Privacy in Tudor London. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Cuddy, Neil. “The Revival of the Entourage: The Bedchamber of James I, 1603–1625”. In The English Court: From the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War, edited by David Starkey, 173–225. London: Longman, 1987.

Day, Richard. Christian Prayers and Meditations in English, French, Italian, Spanish, Greeke, and Latine. London, 1569. Lambeth Palace Library.

Dugan, Holly. “Scent”. In Early Modern Court Culture, edited by Erin Griffey, 428–40. Abingdon: Routledge, 2022.

Fincham, Kenneth. “The King James Bible: Crown, Church and People”. Journal of Ecclesiastical History 71, no. 2 (2020): 77–97.

Finett, John. Finetti Philoxenis: Som Choice Observations of Sr. John Finett knight, and Master of the Ceremonies to the Two Last Kings, Touching the Reception, and Precedence, the Treatment and Audience the Puntillios and Contests of Forren Ambassadors in England. London, 1656.

Foster, Andrew. “Archbishop Richard Neile Revisited”. In Conformity and Orthodoxy in the English Church, c.1560–1660, edited by Peter Lake and Michael C. Questier. 159–78. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2000.

Foster, Andrew. “A Biography of Archbishop Richard Neile (1562–1640)”. DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 1978.

Foster, Andrew. “Neile, Richard (1562–1640)”. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2008), DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/19861.

Glass, Juliet. “The Royal Chapel of the Alcázar: Princely Spectacle in the Spanish Habsburg Court”. PhD thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2004.

Holinshed, Raphael. The Firste Volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande. London, 1577.

Hunt, Arnold. Protestant Bodies: Gesture in the English Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Imrie, John, and John G. Dunbar, ed. Accounts of the Masters of Works. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1957.

Imrie, John, and John G. Dunbar, ed. Accounts of the Masters of Works. Vol. 2, 1616–1649. Edinburgh: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1982.