“From the Chimney to the Chamber”

“From the Chimney to the Chamber”: Recovering a Jacobean Satirical Print

By Helen Pierce

Abstract

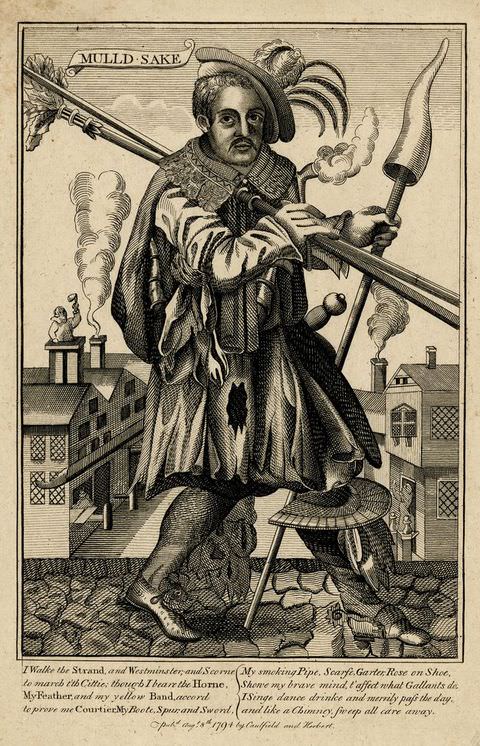

Mulld Sake has been described by the British Museum as “perhaps the most famous of all English prints” during the nineteenth century. Despite its reputation, however, the only certainty about this engraving is its production in London between 1616 and 1621, the active dates of its publisher Compton Holland. This article examines existing conjectures about Mulld Sake and the interpretation of its visual and verbal content, based around the long-standing but problematic assertion that its dandyish subject is the seventeenth-century chimney sweep and highwayman John Cottington. This article presents alternative, overlapping interpretations of the dynamic and complex engraving, revealing the figure as a symbolic representation of favouritism, scandal, and societal ambiguities at King James VI and I’s London court.

Historical Prints and Prized Lots

1Mr. Christie very respectfully informs the public and the curious in ancient English portraits, and English history in particular, that on Friday the 29th instant, he will offer to sale by auction in lots, a most singular, rare and valuable collection of portraits, by the Passe’s, Delaram, &c. &c. some of them unique, being the contents of a very celebrated book that has been preserved 150 years in the Delabere family, and is cited by the Rev. Mr. Grainger, most of them very brilliant impressions, and in the finest condition.1

James Granger’s endorsement gave this auction of seventeenth-century portrait engravings, held at Christie’s London saleroom in March 1811, a distinct importance. The publication in 1769 of his Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution had been a catalyst for the collecting of portrait prints of historical figures among the leisured classes and, while Granger preferred to organise his prints loosely in portfolios, “grangerising” became a byword for extra-illustration—the embellishing and extending of books such as the Biographical History through the pasting in of relevant prints.2 The Delabere sale itself revolved around a collection of Jacobean portrait engravings of English monarchs, the Baziliologia, which had been extensively expanded by its owners beyond its original scope.3 The final lot of this sale, the print known as Mulld Sake, attracted particular attention. Purportedly a unique impression of a portrait of the romanticised Stuart highwayman John Cottington, Mulld Sake represented the pinnacle of early nineteenth-century interest in the collecting of early modern English engravings. As this article will demonstrate, however, Mulld Sake’s content originally spoke to tensions and targets associated with King James’s London court, rather than celebrating roadside robbery.

2James VI and I’s English reign had coincided with notable developments for intaglio printmaking as a commercial venture in London. Single-sheet engravings and book illustrations were far from unknown prior to this point, but were largely the product of trade and exchange, especially with centres of print production in the Low Countries, or the work of visiting artists.4 During the later sixteenth century, however, communities of Dutch, French, and Flemish Protestants had established themselves in the English capital, seeking refuge and freedom of worship as well as employment. Many had brought with them skills in creative industries including painting, goldsmithing, and engraving, which their children went on to consolidate. In 1603 John Sudbury and his nephew George Humble established their print-selling business at Pope’s Head Alley, collaborating directly with professional engravers in the shadow of the commercial hub of the Royal Exchange. Sudbury already dealt in maps and atlases, and together with Humble now expanded that trade to printed pictures, both through imported engravings and those published by the uncle and nephew partnership. Portrait prints made up a significant proportion of their stock, the majority engraved by London-based artists including the prolific Renold Elstrack, the son of an émigré glazier from Liège, and from the mid-1610s Francis Delaram and Simon de Passe, the latter newly arrived from Utrecht. These were primarily half- and full-length representations of monarchs past and present, together with further significant figures associated with the Jacobean court and church.5

4

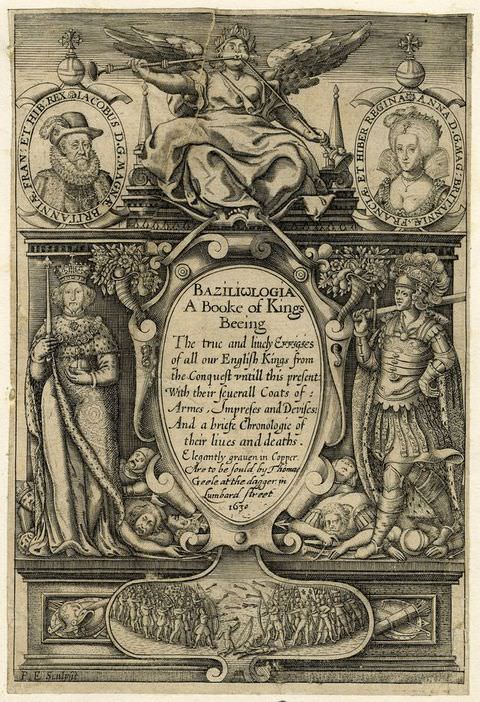

Sudbury and Humble’s dominance of this market for printed images was disrupted in 1616 by the establishment of a neighbouring business in the vicinity of the Royal Exchange. Trading from the Globe in Cornhill, the print seller Compton Holland collaborated with his brother Henry, a printer and member of the Stationers’ Company, to publish a similar range of engraved images. The Hollands also developed a novel and commercially clever project: the Baziliologia, or “book of kings”. This venture took advantage of both the broader cultural interest in portraits of monarchs initially explored by Sudbury and Humble, and King James’s own interest in his personal family tree. Based around a perceived lineage reaching back to Brutus, the ancient king of the Britons, James’s elaborate ancestry provided his own union of the crowns with a valuable element of legitimacy.6 The title page to the Baziliologia was engraved by Renold Elstrack and published by Compton Holland in 1618 (fig. 1). The portraits of James and Anna of Denmark, set in scrolling frames, are heralded by Fame as they oversee the dominant figures of Richard II and William the Conqueror, themselves framed by the fallen corpses and fruitful cornucopia of military victory. Elstrack’s image promises “the true and lively effigies of all our English kings from the Conquest untill this present”. This was not an entirely accurate claim in terms of the publication to follow; but what is certain is that Holland worked primarily with Elstrack to produce a series of intaglio plates, and subsequent engravings, of twenty individual portraits of historical English rulers from William the Conqueror to Henry VII, each approximately 18 × 11.5 centimetres in size. Together, these prints formed a chronological and coherent monarchical sequence. Accompanied by the title page, they could be bound together into a single volume, but Compton Holland’s clientele also had further options. At the sign of the Globe, supplementary portraits of more recent monarchs, as well as spouses and family members (including Anne Boleyn, Anna of Denmark, and Mary Queen of Scots), were also available in the same dimensions as the initial series of kings. This level of choice given to the print buyer as to how many more portraits they wished to add, or perhaps more practically could afford to add, to their personal “book of kings” was a novel commercial element. It is not surprising that every surviving iteration of the 1618 Baziliologia, whether the product of Jacobean print collecting or of longer-term endeavours, differs in content and level of “completeness”.7

6When the Delabere Baziliologia appeared at auction in 1811, it represented an exceptionally expansive portrait set not only of royal sitters but also of aristocrats, church leaders, writers, and adventurers, in 152 separate prints.8 There is a great irony in this seventeenth-century assemblage being subjected to an early nineteenth-century dismantling, with the collection being broken up into individual lots so that its seller could profit from the contemporary craze for historical portrait prints and extra-illustration. The outcome of the Delabere sale certainly reflected this enthusiasm, with the lots achieving just over £600 in total; several years earlier, £50 had been offered by a dealer for this Baziliologia as a single item.9 Since the publication of Granger’s Biographical History of England, prices for seemingly insignificant prints of almost forgotten historical figures had increased exponentially. Horace Walpole, who had provided some assistance to Granger in compiling the Biographical History, noted ruefully in 1770 that, “since the publication, scarce heads in books, not worth three pence, will sell for five guineas”.10 Rarity continued to inform price inflation for portrait prints over the next forty years, reaching what has been termed “the nadir, for contemporaries interested in old prints” at the Delabere sale, and this was especially the case for the star lot of that auction, the print of Mulld Sake (fig. 2).11

8

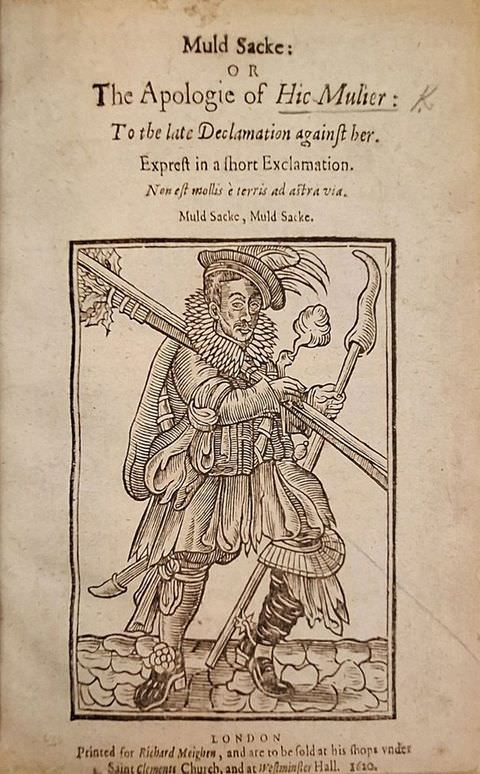

This full-length depiction of a male figure in an eccentric costume, making direct eye contact with the viewer as he strides across an urban street, was the very print that had attracted Granger’s attention when he had viewed the Delabere Baziliologia. Granger’s suggestion that this was a unique extant impression of Mulld Sake, remarking that he “never saw this print but in a very curious and valuable volume of English portraits by the old engravers … now in the possession of John Delabere esq” had markedly enhanced its reputation and perceived value; the print was bought at the 1811 sale on behalf of the marchioness of Bath for the extraordinary sum of £42 10s.12 Together with its seemingly singular status, Mulld Sake’s appeal was also enhanced by its subject matter. It was understood to be the portrait of both a manual labourer and a notorious historical delinquent: the seventeenth-century highwayman John Cottington, who had abandoned an apprenticeship of cleaning chimneys for a largely successful life of crime. Indeed, the association of Mulld Sake with John Cottington has persisted to the present day, yet such a neat connection has proved to be problematic. The print’s unique status was already being questioned at the time of the Delabere sale, and here Granger, and by extension the marchioness of Bath, were mistaken in their regard for it. The British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Princeton University Art Museum all hold impressions of the print today. And this was not Mulld Sake’s only error of assignation. Its long-standing connection to Cottington is misleading as to the engraving’s original subject, or perhaps more appropriately its original intentions. The clarification of those intentions makes sense of its inclusion in several expanded copies of the Baziliologia, which form galleries of early Stuart personalities. Aspects of Mulld Sake do allude to a potent combination of celebrity and criminality, but its content as initially conceived has very little to do with roadside robbery. Instead, it references both social climbing, favouritism, and scandal at James VI and I’s London court, and broader public debates around transgressive behaviours.

12Chimney Sweeps and Highwaymen

The curatorial comment in the British Museum’s online collection refers to Mulld Sake as “perhaps the most famous of all English prints” in the early nineteenth century. What is certain and unquestionable about this engraving, however, is limited to its place of production and a narrow date range.13 Beneath the image and its accompanying verses, a publication line reveals only that it is “to be sold by Compton Holland over against the xchange [sic]”. This establishes that Mulld Sake was created at a point between 1616, when Holland established his business in premises adjacent to the Royal Exchange, and his death in January 1622. Furthermore, both its non-royal subject matter and its larger dimensions, with the platemark measuring 23 × 14.4 centimetres, exclude it from the initial Baziliologia project. Given that Holland’s will, drawn up the previous June, makes specific mention of his declining health and “the arreste of bodilie sicknes”, a publication date prior to mid-1621 is extremely likely.14 In terms of its content, a bold male figure, the eponymous Mulld Sake, dominates the composition with both his confident presence and his contradictory appearance. On his right shoulder he carries two lengthy poles, one with a bushel of holly leaves bound to one end, and in his left hand he holds a further pole topped with a pointed horn; these accessories suggest practical, hands-on activities, whereas his costume alludes to a more elevated lifestyle achieved and lost. Mulld Sake’s collar is dominated by a deep band of elaborate lace, and multiple feathers spring from his bonnet, but his footwear is mismatched with one shoe rose and one spur; a noticeable tear and ragged edges dominate his outer clothes, and a similarly ragged favour is looped around his arm. What then are we to make of this sartorially muddled figure? The verses below the image, which have been largely glossed over by previous commentators, are worth quoting here in full:

13I walke the Strand, and Westminster; and scorne to march i’ th’ Cittie, though I beare the Horne.

My Feather, and my yellow Band accord to prove me Courtier; My Booke, Spurr, and sword:

My smokinge Pipe, Scarfe, Garter, Rose on shoe; showe my brave minde t’ affect what Gallants doe.

I singe, dance, drinke, and merrily passe the day, and like a Chimney sweepe all care away.

This closing reference to the chimney sweep, although grammatically problematic, is suggestive of a character who is able to move easily beyond everyday concerns and responsibilities. This insouciance is further realised in Mulld Sake’s depicted actions. Despite the prominence of his poles and brushes, these accessories have a symbolic rather than a practical significance as he turns his attention to the viewer rather than to the street scene behind him. It is a scene within which he would be largely redundant: as smoke rises up freely from neighbouring chimneys, a woman calls up from her doorway to the busy sweep already at work on the opposite rooftop.

It was not until the early eighteenth century that the character of Mul-Sack (so called for his fondness for drinking mulled sack, a sweetened white wine often prescribed as a medicinal tonic) and the stories of his historic crimes in Stuart England, first became associated with the name of John Cottington; the contents of his life of crime were initially recounted in 1719 in the fifth edition of Alexander Smith’s Compleat History of the Lives and Robberies of the Most Notorious Highway-Men. Smith’s narrative went on to be recycled, reiterated, and romanticised across a range of encyclopaedic collections of rogue literature and biographical histories of pirates, footpads, and highway robbers.15 Mul-Sack was apprenticed to a London chimney sweep at the age of eight, but within five years had run away from his master into the city’s criminal underworld. A period of drinking and pickpocketing followed before he progressed to the greater risks and rewards of highway robbery. By the 1650s, Cottington’s ambition was such that he had robbed Oliver Cromwell twice, and during a brief episode of self-exile in Cologne had encountered and stolen from King Charles II, before a further entanglement with Cromwell led to his arrest and execution. According to Smith, John Cottington, also known as Mul-Sack, was hanged at Smithfield Rounds in 1659, at the age of forty-five.16

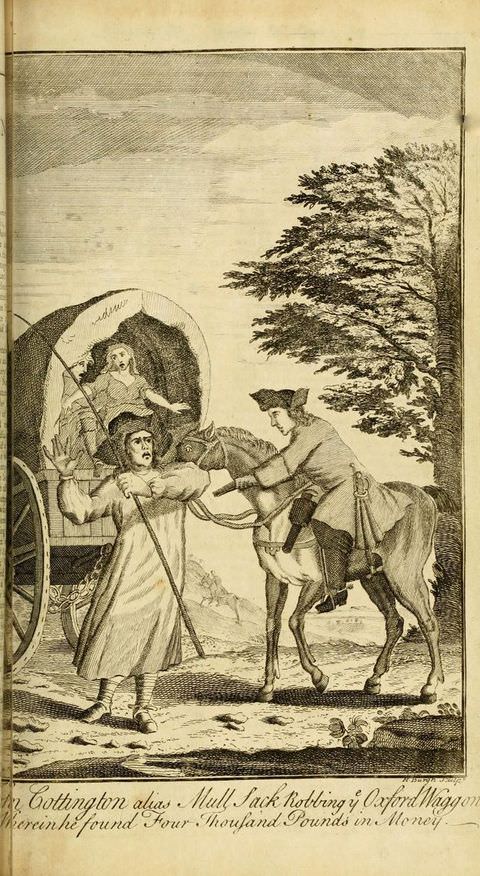

15It is difficult to associate this semi-mythical personality, for whom there is no documentary evidence beyond these later stories, directly with the subject of Holland’s print apart from the name of the protagonist. The print presents an adult male rather than an adolescent boy carrying a chimney sweep’s tools. The narrow window of publication for this engraving of 1616–21 does not align with Smith’s stated birth year for Cottington of 1614.17 It is uncertain whether Cottington ever existed or was simply an amalgamation of historical antiheroes with notable drinking habits. His debut appearance in visual form in the 1742 edition of A General and True History of the Lives and Actions of the Most Famous Highwaymen is generic, in contrast to the extraordinarily individual character depicted in the print, while the History also gives Cottington’s life dates as 1640–85, long after Holland’s death (fig. 3).18

17

The practical explanation for the synthesis of a Jacobean engraving and a Hanoverian biography seems to have revolved around convenience and coincidence. The 1774 supplement to Granger’s Biographical History makes no reference at all to criminality in relation to the print, describing Mulld Sake as a portrait of “a fantastic and humourous chimney sweeper”.19 But, as the apparently unique historical print garnered public attention, interpretation of its content expanded. Grangerising was opening up new commercial possibilities for print sellers and dealers, and James Caulfield, a generation younger than Granger, capitalised on the continual demand for rare printed portraits. His Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of Remarkable Persons, published between 1790 and 1795, reproduced many of the rarer and more unusual prints originally highlighted by Granger alongside brief biographies. It was here that Holland’s Mulld Sake acquired a criminal backstory, as a modern reproduction accompanying John Cottington’s life story. Caulfield would later recount how the artist Sylvester Harding had been permitted to make a drawing of the print when it formed part of the Delabere Baziliologia, from which a new engraving had been produced (fig. 4).20 The print seller would have recognised the commercial value of Harding’s sketch of a supposedly unique image—and the convenience and commercial benefits of projecting the imagery of Holland’s striking character onto a romanticised biography of a historical highwayman. A second edition of Caulfield’s publication was issued in 1813, following the Delabere sale, which further consolidated and reinforced the specific identity for an eccentrically dressed Jacobean “chimney sweep”.

19

A rather different character, however, emerges from the verses that supplement the Mulld Sake engraving. This is a figure in motion, for whom different areas of London signify different socioeconomic conditions; Mulld Sake’s preference is for Westminster and the particular neighbourhood of the Strand, lined with grand townhouses reserved for the Elizabethan and Jacobean elite, rather than the City to the east. His self-confidence in his capacity to navigate such spaces is expressed through his selection of costume and accoutrements: “My Feather, and my yellow Band accord to prove me Courtier”, while further distinctive accessories such as the pipe and shoe rose “showe my brave minde t’ affect what Gallants doe”, mimicking the behaviours of modish young men. He focuses on fine fashion and personal appearance as a guaranteed entry point to the role of the courtier, a part that can be played as well as assumed naturally through status and birthright. His words chime closely with those of a verse libel of the early 1620s, which looked back to the rapid rise of certain personalities during King James’s English reign: “Thus swarmes the Courte with youthfull gallants brave, and happie he, who can the king’s love have”.21

21“Jocky Can Caper as High as an Earle”

What then of the king’s “love”?22 Prior to his accession to the English throne, the early years of James’s Scottish reign had seen the adolescent monarch develop a close relationship with his older cousin Esmé Stuart, Seigneur d’Aubigny and, later, first duke of Lennox. Stuart had been raised in France, and his presence at Holyroodhouse between 1579 and 1582 was as a cultured and sophisticated mentor for the king. However, that proximity to and perceived influence on the young James had prompted concerns from members of both the kirk and the court. In London, James focused his attentions on younger male courtiers, who were drawn into his orbit and rewarded with titles and positions according to their appearance, charm, and bearing rather than their political and diplomatic abilities. The most prominent of these young men were firstly Robert Kerr (or Carr, as he was known in England) and subsequently, George Villiers, each of whom swiftly and notably rose, through their interactions with the king, from the “middling elite” to senior aristocratic status as earl of Somerset and duke of Buckingham respectively.23 Kerr was born in 1585 or 1586, the youngest son of Thomas Ker, laird of Ferniehirst. An infant at most at the time of his father’s death, Kerr was brought up in the royal household at Edinburgh, possibly due to Ferniehirst’s loyalties to Esmé Stuart, and, following a brief period as a page to George Home, the lord treasurer of Scotland, the young Kerr joined his king in the journey south to London in 1603, going on to serve as one of James’s grooms of the bedchamber. This position regularly brought him into close personal contact with James, and between 1607 and 1613 a series of preferments saw Kerr knighted, granted land and property, created Viscount Rochester and finally earl of Somerset.24

22Carr’s social progression did not pass unnoticed, and he was the subject of critique, gossip, and rumour in parallel with his personal advancement, preserved primarily through the medium of verse libels, which commonly circulated in manuscript format. Such material reflected the factional nature of the political sphere in early Stuart England. The physical and symbolic relocation of members of the Edinburgh court to London from 1603 onwards brought with it a new hierarchical framework to be negotiated by the elite at Whitehall and beyond. Where openly printed critiques faced censorship, these handwritten sentiments circulated privately against the “incoming” Scots and their apparent monopolisation of coveted appointments and associated benefits. Several of these attacks appear to have been penned in the wake of Kerr’s 1613 marriage to Frances Howard, daughter of the earl of Suffolk, one observing how “They beg al our money lands livings & lives, Nay more they beginne to get our fayre wives”. Setting up further implied divisions between the Scots and the English, the same verses recounted how the once modest and homely outfits that had characterised James’s northern courtiers were now being exchanged in London for luxurious fashions:

25Ffor now every Scotshman, yt was lately wont

To weare the cow hide of an old Scottish runt

His bonny blew bonnet, is now layd aside

In velvet and scarlet proud Jocky must ride …

His py’de motly jerkin al threadbare and old

Is now turnd to scarlet and ore lac’t with gold

His straw hat to bever, his hatband to perle

And Jocky can caper as high as an Earle.25

With Robert Kerr’s elevation to the earldom of Somerset in November 1613, and his marriage to Frances Howard the following month, satirical lines such as these could resonate with the reader for multiple reasons, as a polemic against the ambitious Scot setting up in England, overstepping accepted boundaries of status and behaviour, ignoring conventions of dress, and coveting an English bride and English titles. In the coming years, ruminations on the currency of costume would continue to be associated with Kerr and his circle, even as his courtly trajectory was about to be dramatically halted. And it is the mention in Mulld Sake of a specific sartorial effect that brings Robert Kerr, earl of Somerset, quite literally into the picture.

In May 1616 the earl and countess of Somerset stood trial for murder. This dramatic crime and cause célèbre revolved around the death of Sir Thomas Overbury, once a friend and adviser to Kerr, who had been confined to the Tower of London in 1613; the ostensible reason for his imprisonment was the refusal of an ambassadorship offered by the king, but Overbury’s vocal opposition to the Howard–Kerr marriage then being arranged had also played a role in his removal from court. Although Overbury died in the Tower of unknown causes in September that year, rumours of his having been poisoned did not emerge until two years later, with accusations made against the Somersets and an entourage of accomplices. The countess pleaded guilty to the charges against her and, while her husband made no confession, both were committed to the Tower of London until they were pardoned in January 1622. Others associated with the Overbury affair were not so fortunate: Sir Gervase Elwes, lieutenant of the Tower, Richard Weston, Overbury’s keeper while imprisoned, and Anne Turner, a member of the countess’s household, were all executed for their apparent involvement in the administering of poison to Overbury.26

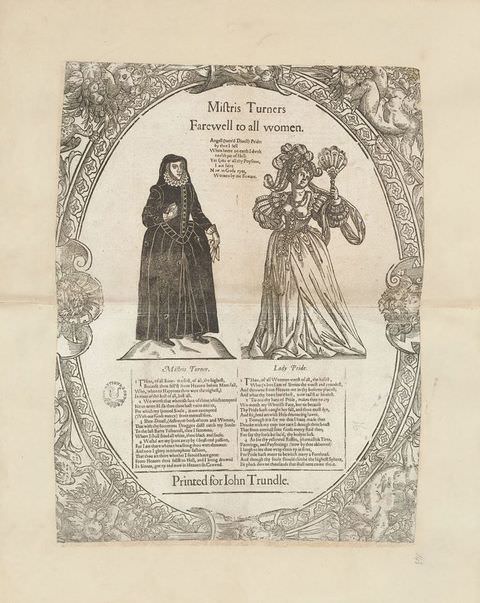

26Anne Turner, the widow of George Turner, a physician once highly regarded by Queen Elizabeth I, received particular public attention for her crimes. Castigated at her trial for a range of misdemeanours culminating in Overbury’s death, including spell-casting and the procurement of poisons, she was characterised by Lord Chief Justice Edward Coke as “a whore, a bawd, a sorcerer, a witch, a papist, a felon and a murderer”.27 Turner was hanged at Tyburn in November 1615, reportedly after transforming herself on the scaffold from a wicked deviant to a modest and penitent sinner. This transition was emphasised in Mistris Turners Farewell to All Women, one of many broadsides and pamphlets published in response to the Overbury murder trials, by the inclusion of two woodcut images that contrast Turner with Lady Pride (fig. 5). Almost certainly taken from stock woodblocks available to the broadside’s publisher John Trundle, Pride admires her own lavish appearance, including an exceptionally low-cut gown, in a hand mirror, while Turner is clad in modest black, her accessories being a prayer book and handkerchief.28 Beneath the woodcuts, each woman makes a speech condemning the other. Pride notes that Turner has cast away many of her previous accessories, including “thy yellowed Ruffes, phantastick Tires, Paintings, and Poysonings (now by thee abhorred)”. According to reports of her trial, Turner had attended each day wearing a starched collar (also known as a “band”) and cuffs both dyed yellow with saffron, a fashion practice in elite circles. She may have hoped that these accessories would bolster her status as a woman with an elevated social position, but her sartorial choices quickly backfired.29 According to Simonds d’Ewes’s account, Turner having “first brought up that vain and foolish use of yellow starch … when she was afterwards executed at Tyburn, the hangman had his band and cuffs of the same colour, which made many after that day of either sex to forbear the use of that coloured starch, till it at last grew generally to be detested and disused”.30 Other descriptions of the execution maintained that Turner herself was forced to wear this marker of pride and ambition despite her public repentance.31

27

Whatever the truth of the yellow band on the Tyburn scaffold, this fashion had become synonymous with Turner’s pride and overreach; audiences attending Ben Jonson’s latest play The Devil Is an Ass in 1616 would no doubt have laughed at Satan’s line that socially ambitious “Car-men are got into the yellow starch, and Chimney-sweepers to their tabacco, and strong-waters”.32 Jonson could have selected from a range of manual workers to illustrate the implied economic reach of Anne Turner’s starched collar, such was its persistence in the public’s consciousness that even carters were now dabbling in the fashion. The specific mention of “car-men”, however, in the same breath as chimney sweeps now indulging in alcohol and tobacco gestures to a broader vocabulary of critique generated by the earl of Somerset’s involvement in the Overbury scandal, and his present confinement in the Tower. Mulld Sake’s own highlighting of his “yellow Band … to prove me Courtier”, and the prominent display of his tobacco pipe, bring this chimney sweep, with his self-proclaimed ability to move in elite circles, close to the disgraced figure of Kerr.

32Prints and Pamphlets

Satan’s quip about carters in collars was by no means the only instance of Anne Turner’s sartorial transgressions extending to members of her circle. The countess of Somerset, having already acquired a problematic reputation following the annulment of her first marriage to marry Robert Kerr, was now held up by polemical pamphleteers as a vivid example of a woman whose murderous intentions were reflected in her outward appearance and pursuit of a distinctly “masculine” style. There are two known states of a half-length portrait of the countess, signed by Simon de Passe and published by Compton Holland (figs. 6 and 7). Simon initially worked for Holland during his stay in England between 1616 and 1621, but by 1618 he had transferred his professional loyalty to Sudbury and Humble, helping to narrow the dating of the original state of the countess’s likeness.33 In the second state, not necessarily revised by Simon de Passe’s hand, the countess’s hair has been cropped and a brimmed hat added, a nod to changing fashions that many commentators found to be disturbing. Such concerns reached a crescendo in 1620, with the king’s command to the bishop of London that his clergy “inveigh vehemently and bitterly in theyre sermons against the insolencie of our women, and theyre wearing of brode brimd hats, pointed dublets, theyre haire cut short or shorne”.34 This insolence was perceived to be a direct consequence of women adopting masculine modes of dress, and by extension drew attention to the effeminacy of men who curled their hair into long locks and adorned them with powder. A lively pamphlet debate followed King James’s instructions and invective, with Hic-Mulier, or The Man-Woman providing a detailed description of “you Masculine-women” as “halfe man, halfe woman, halfe fish, halfe flesh, halfe beast, halfe monster”, before he notes their “false armoury of Yellow starch”.35 This reference to Turner’s transgressive collar and cuffs may be read more generally as a badge of sartorial dishonour, but Hic-Mulier’s inclusion of twelve lines of verse from Overbury’s posthumously published poem A Wife, a lightly veiled critique of Frances Howard, maintained the Somersets’ relevance to debates around dress, criminality, and correct modes of behaviour. A response to Hic-Mulier followed in the form of Haec-Vir. Both pamphlets were printed for John Trundle, a well-known publisher of popular literature (also responsible for Mistris Turner’s Farewell to All Women), and their debate in print seems to have been designed to generate profits for Trundle, as well as contributing to broader discussions of a topical issue.36 Here, the “womanish man” and the “mannish woman” engage in conversation and, after much mutual critique, decide to exchange their outfits and accessories in order to “live nobly like our selves, ever sober, ever discreet, ever worthy; true men and true women” in a neat return to gendered expectations.37 Prior to this reconciliation, however, Hic-Mulier is derided by her counterpart as a Janus-like creature made up of hybrid elements, one of these being “halfe Mull’d Sacke the Chimney Sweeper … the one for a Yellow Ruffe”.38

33

Mulld Sake is also referenced in a third pamphlet published in 1620, as a character conversing directly with that of Hic-Mulier. Printed for Richard Meighen rather than John Trundle, Mulde Sacke, or The Apologie of Hic Mulier appears to have been written to take further advantage of the original pamphlet debate around gendered fashions, rather than expanding its themes. It opens with a brief dedication to the chimney sweep made by Hic-Mulier, the mannish woman, before progressing to reiterate much of the content of the first two pamphlets. In that dedication, the sweep’s dedication to contemporary fashion is carefully detailed: “One day you weare yellow Bands, Feathers, Scarffes; cuts your haire and powders it, paints your face so all the weeke, that upon Sunday, a pound of sope will not reduce it to the right colour”.39 Such words align closely with those of the retrospective pamphlet The Five Yeares of King James, published in 1643, where Robert Kerr’s descent into murderous scandal is characterised by his adoption of “new fashions … so that he might show more beautiful and faire, and that his favour and personage might be made more manifest to the world, and for this purpose yellow bands, dusted hair, curled, crisped, frizzled”.40 Of further significance here is the reuse of Holland’s engraving for Mulde Sacke, or The Apologie of Hic Mulier, now worked up as a simpler woodcut, which dominates the pamphlet’s title page (fig. 8). As well as representing sartorial ambiguity in relation to social class, the character of Mulld Sake is now drawn into debates around gendered fashion and transgression.

39

A copy of the Mulde Sacke pamphlet belonging to the British Library includes an annotation on its inner cover in the hand of the nineteenth-century writer and book collector George Daniel: “A very rare and curious Tract illustrating the manners & customs of Old London … I possess a beautiful impression of the scarce and valuable print (the Original) of ‘Mulld Sacke’”.41 Daniel did indeed hold in his collection the impression of Mulld Sake that is now held by the Princeton University Art Museum and that contains further annotations in his hand. His assertion, underlined for emphasis on the title page of the pamphlet published by Richard Meighen, adds weight to the strong likelihood that the initial image of this “chimney sweep” was Holland’s print, which served as a template for subsequent copies. This is an early example of the flexibility of an engraving and how it could be adapted to serve as an illustration for specific as well as more generic targets and circumstances. This adaptability would go on to be further realised in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

41Returning to Compton Holland’s engraving, it is difficult, however, to connect it to certain of those criticisms levelled at the sweep by Hic-Mulier, regarding cropped hair and painted faces. This Mulld Sake is conspicuous by the sheer confusion of his extravagant and muddled costume: the sweep’s brushes set against the sword and extravagant headgear, the mismatched footwear, and the tattered favour all point to a lack of understanding of how to wear and preserve such badges of status and wealth. This is further compounded by the material that stands proud beneath his right knee, a singular accessory not found on his other leg. This is a pickadil, intended to be worn around the neck as a support over which a standing collar or ruff would be laid.42 An extant example in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum matches Mulld Sake’s legwear, with its strip of satin clearly visible over a semi-circular framework (fig. 9). The misunderstanding of how this essential element of formal costume should be worn echoes critical views of Robert Kerr and his fellow Scottish courtiers in London, who had been elevated from apparently lowly social origins to positions of social and political significance while lacking in the knowledge of appropriate comportment and self-fashioning. That the specifics of Kerr’s biography did not fit this rags-to-riches narrative did not matter. What mattered was that his actions, like the sartorial sins of his wife and of Anne Turner, contributed to a demonstration of inner ambitions and transgressions finding expression in outward appearance.

42

But why would a notorious courtier and favourite be referred to in a satirical image with allusions to a chimney sweep? Mulld Sake as a critique of Robert Kerr appears to rely on highly topical and specific knowledge that may, ironically, have aided the engraving’s later transformation into John Cottington. Beyond Ben Jonson’s nod to car-men and sweeps coveting yellow bands and tobacco, one contemporary poem, “In England there lives a jolly Sire”, imagines how Kerr’s early elevation to the position of gentleman of the bedchamber had come from his ability to make “our King’s good grace a fire”; this tantalising suggestion of sexual contact between the king and his favourite is intimated, but never confirmed, by the subsequent line revealing how the Jolly Sire thus “leapt from the chimney to the chamber”, that is, from a lowly environment to one of riches and reward.43 With “There lives a jolly Sire” known today in only one collection of early Stuart verse libels, there have been reservations regarding its circulation and reach. However, the 1662 pamphlet The Chimney’s Scuffle’s reference to “That old Mull’d-Sack, who to such fortunes crept, And from a chimney to a Mannor lept” suggests a certain longevity to this particular image of social climbing.44

43While connections between Mulld Sake and Robert Kerr have been identified here through a close contextual examination of the engraving, there is less certainty about the practicalities of its artist and the circumstances of its production. Neither an engraver’s name nor initials are present in the image, but of the known engravers working with and for Compton Holland, Renold Elstrack is a likely candidate. Whereas Simon de Passe’s brief period of collaboration with Holland focused on portrait engravings, and Francis Delaram’s extant prints encompass portraits and title pages, Elstrack, who worked extensively on the 1618 Baziliologia for Holland, also produced satirical and politically topical images. His name appears on Behold Kind Husbands, a satire on society’s apparent surfeit of good men and lack of corresponding good wives, entered into the Stationers’ Register in July 1620 and known today through a unique impression republished in the later seventeenth century.45 Its original appearance in the summer of 1620 would certainly have been responsive to broader commentaries around challenging and unruly women. Elstrack has also been identified by this author as the engraver of King James I Holding the Pope’s Nose to the Grindstone, an anti-Catholic polemic produced and published anonymously in 1614, and wisely so, given the protestations of the Spanish ambassador in London as to its existence and the subsequent destruction of the printing plate.46

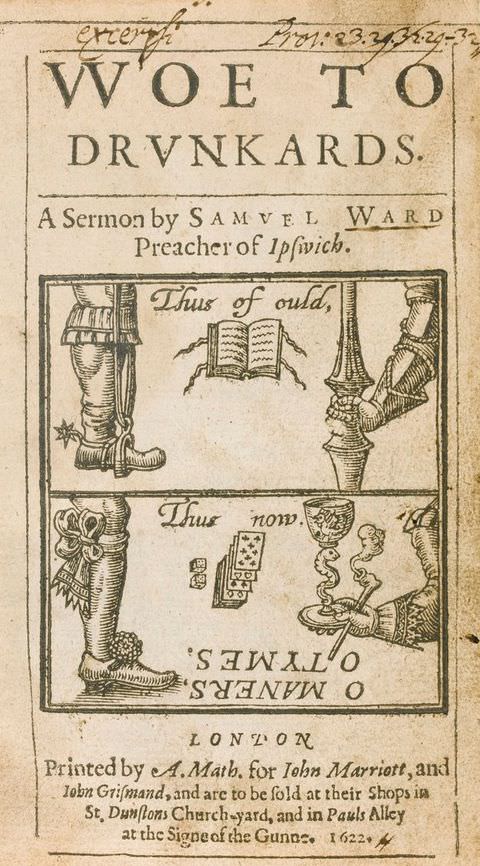

45Even with no recorded engraver, Elstrack or otherwise, the inclusion of Compton Holland’s name and premises in the image underlines Mulld Sake’s status as an allusive rather than specific critique of an individual courtier and their behaviour. It would make little commercial or political sense to directly target the now imprisoned and disgraced Kerr; rather, Kerr acts here as a cipher in a visual commentary on sartorial transgression, as a reminder of recent misconduct, and as a warning in relation to renewed anxieties around the king’s present favourite. James’s own interests had been shifting, even prior to the Overbury scandal and its implications, towards a new young gentleman of the court. Between the mid-1610s and the mid-1620s, George Villiers’s rise from cupbearer to gentleman of the bedchamber, from Viscount Villiers to earl, marquess, and eventually duke of Buckingham, was meteoric. Positions of increasing courtly responsibility were matched by military promotion seemingly based on the king’s affections rather than Villiers’s martial experience. His appointment as Lord High Admiral in 1619, combined with James’s continued pursuit of peace and diplomacy as the wars of religion took hold in Europe, led to coded accusations of the effeminisation of English manhood.47 The visualisation of such sentiments can be seen in the frontispiece to Samuel Ward’s 1622 sermon Woe to Drunkards, where the spurs, armour, lance, and Bible of the English knight “of ould” have been replaced by the shoe rose, cards, dice, tobacco pipe, and lace cuffs of the present-day courtier (fig. 10). Mulld Sake’s own deliberately muddled iconography anticipates Ward’s title page, a fuller expression of the social and political anxieties that were being worked through in the former.

47

Mulld Sake belongs to a small group of surviving Jacobean graphic satires which explore varying themes, some clearly targeting individual offenders within social or political contexts, while others offer more generalised commentaries on topical matters. The pope and his associated Catholic cohort were acceptably and directly depicted as recognisable figures in unflattering and often physically comedic circumstances, while Anne Turner was visually paralleled with Lady Pride, in acknowledgement of her execution. In contrast, the earl and countess of Somerset faced more subtle and expansive visual critiques: the danger of the “masculine-woman” with her cropped hair exploited by the reworking of Simon de Passe’s portrait of the countess, and the negative implications of social climbing raised in the allusions to her husband in Mulld Sake. With its clever combination of specificity and generality, it is not surprising that both the image and idea of Mulld Sake would go on to be adapted to suit new interests both in historic criminality, and in historic portraiture, rather than remaining tied to its original commentary on mobility, ambition and sartorial transgression within and beyond the Jacobean court. There is minimal likelihood that this engraving’s initial subject matter was John Cottington, and the association between Mulld Sake and the highwayman which has persisted since the early eighteenth century must now be reconsidered. However, the inclusion of Mulld Sake within the oeuvre of Jacobean graphic satire does not diminish its later reinvention, but is rather a demonstration of that satirical print’s own porosity and capacity to fit to new narratives over time.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray, as editors of this special issue of British Art Studies, for all their hard work in proposing, arranging, and bringing this publication to fruition. The contributors’ workshop held in the summer of 2024, and supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, was a fantastic opportunity to make connections, share ideas, and offer feedback on article proposals. The subsequent comments of the two anonymous readers have proved invaluable in further shaping this article’s argument and direction. I’m also grateful to Baillie Card for her patience, and to Maria Hayward for her guidance on some particular details of Jacobean elite costume, not least for introducing me to the pickadil.

About the author

-

Helen Pierce is Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of Aberdeen, where she specialises in early modern British art, with a particular focus on printed images, graphic satire, and political polemic. She is the author of Unseemly Pictures: Graphic Satire and Politics in Early Modern England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008) and her new study The Profaned Pencil: A History of British Political Caricature, 1600–1860 is forthcoming from Reaktion Books.

Footnotes

-

1

Morning Chronicle, 20 March 1811. ↩︎

-

2

James Granger, A Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution (London: T. Davies, 1769). On “grangerising” as an artistic and cultural phenomenon in later Georgian Britain, see Lucy Peltz, Facing the Text: Extra Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769–1840 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 2017). ↩︎

-

3

It is not clear whether further prints were added to the Delabere Baziliologia solely by its initial Jacobean owner or the collection was gradually expanded across the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Several intact expanded iterations of the Baziliologia in seventeenth-century bindings are known, including examples at the Bodleian Library and at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. ↩︎

-

4

Antony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 1603–1689 (London: British Museum Press, 1998), 13–14. See also Arthur M. Hind’s Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, 3 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952–64), vol. 1. Although printed images were imported into Scotland, as evidenced by their adaptation in both murals and portable oil paintings, intaglio prints were not produced in Scotland until the very end of the seventeenth century, largely in the field of map-making. ↩︎

-

5

Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 45–63. ↩︎

-

6

On James’s genealogy and the significance of the Brutus connection, see Arnold Hunt, Dora Thornton, and George Dalgliesh, “A Jacobean Antiquary Reassessed: Thomas Lyte, the Lyte Genealogy and the Lyte Jewel”, Antiquaries Journal 96 (2016): 169–205. ↩︎

-

7

The contents of extant expanded sets of the Baziliologia can be consulted in Howard C. Levis, Baziliologia, a Booke of Kings: Notes on a Rare Series of Engraved English Portraits from William the Conqueror to James I (New York: Grolier Club, 1913); and Hind, Engraving in England, 2:135–38. ↩︎

-

8

A Catalogue of a Most Singular, Rare and Valuable Collection of Portraits by the Passes, Delaram, &c. (London, 1811). ↩︎

-

9

Walter F. Tiffin, Gossip about Portraits, Principally Engraved Portraits (London: H. G. Bohn, 1866), 178–79. ↩︎

-

10

The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, ed. Wilmarth Sheldon Lewis, 48 vols. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1937–83), 23:211. ↩︎

-

11

Peltz, Facing the Text, 302. ↩︎

-

12

James Granger and Horace Walpole, A Supplement, Consisting of Corrections and Large Additions, to A Biographical History of England (London: T. Davies, 1774), 487; Levis, Baziliologia, A Booke of Kings, 160; A Catalogue of a Most Singular, Rare and Valuable Collection, 44. For context, only a handful of the 152 prints at the auction were secured for more than £15. The nearest competitor to Mulld Sake was a portrait by Elstrack of John Harington, second Baron Harington, described in A Catalogue of a Most Singular, Rare and Valuable Collection as “very fine, unique”, which sold for £33 11s. ↩︎

-

13

Mulld Sake, British Museum, 1863,0725.199, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1863-0725-199. ↩︎

-

14

Will of Compton Holland, Leather Seller of London, proved 11 January 1622, The National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/139/27. Holland’s wife, Hester, continued to publish a number of plates from the Globe until 1623, but without the inclusion of his name. See Antony Griffiths, “Holland, Compton”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004), DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/64982. ↩︎

-

15

On the popularity of criminal biography as a literary genre during this period, see Lincoln B. Faller, Turned to Account: The Forms and Functions of Criminal Biography in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987). ↩︎

-

16

Alexander Smith, A Compleat History of the Lives and Robberies of the Most Notorious Highway-Men, 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: Samuel Briscoe, 1719), 2:217–26. ↩︎

-

17

James Caulfield suggests an earlier birth date for Cottington of 1604, but this is still problematic for an engraving depicting an adult male published between 1616 and 1621. James Caulfield, Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of Remarkable Persons (London: James Caulfield and Messrs Harding, 1794–95). ↩︎

-

18

Charles Johnson, A General and True History of the Lives and Actions of the Most Famous Highwaymen, Murderers, Street-Robbers, &c. (Birmingham: R. Walker, 1742), 314. ↩︎

-

19

Granger and Walpole, A Supplement, Consisting of Corrections and Large Additions, 486. ↩︎

-

20

James Caulfield, Calcographiana: The Printsellers Chronicle and Collectors Guide to the Knowledge and Value of Engraved British Portraits (London: G. Smeeton, 1814), 117. ↩︎

-

21

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Eng. poet. c. 50, fol. 1, quoted in Helen Pierce, Unseemly Pictures: Graphic Satire and Politics in Early Modern England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 13. ↩︎

-

22

On James’s sexuality, see James Loxley, “Unseemly Caresses: The Queer Style of James VI and I”, DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/jloxley. ↩︎

-

23

Contemporary views on James’s treatment of Kerr and Villiers, and the subsequent development of a modern historiography around the king’s sexual preferences, are discussed in Michael B. Young, “James VI and I: Time for a Reconsideration”, Journal of British Studies 51, no. 3 (2012): 540–67. ↩︎

-

24

In correspondence from London of 30 December 1607, John Chamberlain informed Dudley Carleton that “Sir Robert Carre a younge Scot and new favourite is lately sworne gentleman of the bedchamber”. The Letters of John Chamberlain, ed. Norman E. McClure, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939), 1:249. ↩︎

-

25

“On The Scots”, Folger Shakespeare Library, MS V.a.345, Poetical Miscellany, circa 1630, 287–88. This significant collection of verses reproduces both poems and text extracts from a period of over forty years. See also the undated verse “Well Met Jockie Whether Away”, which highlights the Scots courtiers’ shifting fortunes and fashions in Jacobean England. https://www.earlystuartlibels.net/htdocs/scots_section/E5.html. ↩︎

-

26

On Overbury’s death, the chief actors within the poisoning “plot” and its repercussions, see Alastair Bellany, The Politics of Court Scandal in Early Modern England: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); David Lindley, The Trials of Frances Howard: Fact and Fiction at the Court of King James (London: Routledge, 1993). ↩︎

-

27

Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason, 33 vols. (London: Longman, 1809–28), 2:935. ↩︎

-

28

A very similar figure of Lady Pride was recorded by Thomas Trevilian in his “Great Book” of 1616, which suggests that it was a familiar emblem in Jacobean London. See Nicholas Barker, ed., The Great Book of Thomas Trevilian: A Facsimile of the Manuscript in the Wormsley Library, 2 vols. (London: Roxburghe Club, 2000), 2:321. ↩︎

-

29

On the significance of, and anxieties around, the yellow starched collar in contemporary court culture, see Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass, Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 59–86. ↩︎

-

30

The Autobiography and Correspondence of Sir Simonds D’Ewes, Bart., during the Reigns of James I and Charles I, ed. James O. Halliwell, 2 vols. (London: Richard Bentley, 1845), 1:79. ↩︎

-

31

Alastair Bellany, “Mistress Turner’s Deadly Sins: Sartorial Transgression, Court Scandal and Politics in Early Stuart England”, Huntington Library Quarterly 58, no. 2 (1996): 189. ↩︎

-

32

The Workes of Benjamin Jonson (London: Richard Meighen, 1641), 97. ↩︎

-

33

Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 56. ↩︎

-

34

The Letters of John Chamberlain, 2:286–87. ↩︎

-

35

Hic Mulier, or The Man-Woman (London: J[ohn] T[rundle], 1620), sigs. A3v–A4. ↩︎

-

36

On the Hic-Mulier and Haec-Vir pamphlets debate see Sandra Clark, “‘Hic Mulier’, ‘Haec Vir’, and the Controversy over Masculine Women”, Studies in Philology 82, no. 2 (1985): 157–83. ↩︎

-

37

Haec-Vir, or The Womanish-Man (London: J[ohn] T[rundle], 1620), sig. C4. ↩︎

-

38

Haec-Vir, sig. A4. ↩︎

-

39

Muld Sack, or The Apologie of Hic-Mulier (London: William Stansby for Richard Meighen, 1620), sig. A3–A3v. ↩︎

-

40

The Five Yeares of King James, or The Condition of the State of England (London, 1643), 21. ↩︎

-

41

British Library, C.40.d.44. ↩︎

-

42

Maria Hayward, Stuart Style: Monarchy, Dress and the Scottish Male Elite (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020), 325. ↩︎

-

43

“In England there lives a jolly Sire”, British Library, Add. MS 15476, fol. 19r, reproduced at https://www.earlystuartlibels.net/htdocs/overbury_murder_section/H2.html. ↩︎

-

44

The Chimneys Scuffle (London, 1662), 1. ↩︎

-

45

Sheila O’Connell, “The Peel Collection in New York”, Print Quarterly 15, no. 1 (1998): 66–67. ↩︎

-

46

Helen Pierce, “The Pope and the Grindstone: A Jacobean Satirical Print”, Print Quarterly 40, no. 2 (2023): 131–37. ↩︎

-

47

Kevin Sharpe, Image Wars: Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 129. ↩︎

Bibliography

Barker, Nicholas, ed. The Great Book of Thomas Trevilian: A Facsimile of the Manuscript in the Wormsley Library. London: Roxburghe Club, 2000.

Bellany, Alastair. “Mistress Turner’s Deadly Sins: Sartorial Transgression, Court Scandal and Politics in Early Stuart England”. Huntington Library Quarterly 58, no. 2 (1996): 179–210.

Bellany, Alastair. The Politics of Court Scandal in Early Modern England: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603–1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

A Catalogue of a Most Singular, Rare and Valuable Collection of Portraits by the Passes, Delaram, &c. London, 1811.

Caulfield, James. Calcographiana: The Printsellers Chronicle and Collectors Guide to the Knowledge and Value of Engraved British Portraits. London: G. Smeeton, 1814.

Caulfield, James. Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of Remarkable Persons. London: James Caulfield and Messrs Harding, 1794–95.

Chamberlain, John. The Letters of John Chamberlain. Edited by Norman E. McClure. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939.

The Chimneys Scuffle. London, 1662.

Clark, Sandra. “‘Hic Mulier’, ‘Haec Vir’, and the Controversy over Masculine Women”. Studies in Philology 82, no. 2 (1985): 157–83.

Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason. London: Longman, 1809–28.

D’Ewes, Simonds. The Autobiography and Correspondence of Sir Simonds D’Ewes, Bart., during the Reigns of James I and Charles I. Edited by James O. Halliwell. London: Richard Bentley, 1845.

Faller, Lincoln B. Turned to Account: The Forms and Functions of Criminal Biography in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

The Five Yeares of King James, or The Condition of the State of England. London, 1643.

Folger Shakespeare Library. MS V.a.345. Poetical Miscellany, c. 1630.

Granger, James. A Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. London: T. Davies, 1769.

Granger, James, and Horace Walpole. A Supplement, Consisting of Corrections and Large Additions, to A Biographical History of England. London: T. Davies, 1774.

Griffiths, Antony. “Holland, Compton”. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/64982.

Griffiths, Antony. The Print in Stuart Britain, 1603–1689. London: British Museum Press, 1998.

Haec-Vir, or The Womanish-Man. London: J[ohn] T[rundle], 1620.

Hayward, Maria. Stuart Style: Monarchy, Dress and the Scottish Male Elite. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

Hic Mulier, or The Man-Woman. London: J[ohn] T[rundle], 1620.

Hind, Arthur M. Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952–64.

Hunt, Arnold, Dora Thornton, and George Dalgliesh. “A Jacobean Antiquary Reassessed: Thomas Lyte, the Lyte Genealogy and the Lyte Jewel”. Antiquaries Journal 96 (2016): 169–205.

Johnson, Charles. A General and True History of the Lives and Actions of the Most Famous Highwaymen, Murderers, Street-Robbers, &c. Birmingham: R. Walker, 1742.

Jones, Ann Rosalind, and Peter Stallybrass. Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Jonson, Benjamin. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. London: Richard Meighen, 1641.

Levis, Howard C. Baziliologia, a Booke of Kings: Notes on a Rare Series of Engraved English Portraits from William the Conqueror to James I. New York: Grolier Club, 1913.

Lewis, Wilmarth Sheldon, ed. The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1937–83.

Lindley, David. The Trials of Frances Howard: Fact and Fiction at the Court of King James. London: Routledge, 1993.

Muld Sack, or The Apologie of Hic-Mulier. London: William Stansby for Richard Meighen, 1620.

The National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/139/27. Will of Compton Holland, Leather Seller of London, proved 11 January 1622.

O’Connell, Sheila. “The Peel Collection in New York”. Print Quarterly 15, no. 1 (1998): 66–67.

Peltz, Lucy. Facing the Text: Extra Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769–1840. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 2017.

Pierce, Helen. “The Pope and the Grindstone: A Jacobean Satirical Print”. Print Quarterly 40, no. 2 (2023): 131–37.

Pierce, Helen. Unseemly Pictures: Graphic Satire and Politics in Early Modern England. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Sharpe, Kevin. Image Wars: Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Smith, Alexander. A Compleat History of the Lives and Robberies of the Most Notorious Highway-Men. 5th ed. 2 vols. London: Samuel Briscoe, 1719.

Tiffin, Walter F. Gossip about Portraits, Principally Engraved Portraits. London: H. G. Bohn, 1866.

Young, Michael B. “James VI and I: Time for a Reconsideration”. Journal of British Studies 51, no. 3 (2012): 540–67.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/hpierce |

| Cite as | Pierce, Helen. “‘From the Chimney to the Chamber’: Recovering a Jacobean Satirical Print.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/hpierce. |