James VI and I’s Banqueting Houses

James VI and I’s Banqueting Houses: A Transatlantic Perspective

By Lauren Working

Abstract

In 1606, as agents of the newly chartered Virginia Company set their sights on Indigenous lands in North America, King James VI and I signed off on another project—the building of a new banqueting house to replace the dilapidated structure that had hosted many of Whitehall’s entertainments since 1581. When a fire destroyed this banqueting house in 1619, James immediately enlisted the architect Inigo Jones to design a replacement, built on the same foundations. While scholars have established the significance of Jones’s Banqueting House in Jacobean statecraft and artistic patronage, this article considers how both of James’s banqueting houses and the performances staged in them played a role in shaping the king’s articulation of courtly civility and imperial sovereignty from a transatlantic perspective. The first half sets up the significance of James’s banqueting houses as political and social spaces that informed colonial interests in early Stuart London, in masques such as The Maske of Flowers (1614), which characterised Tobacco as an Algonquian guardian spirit, and The Vision of Delight (1617), a performance attended by Pocahontas and the shaman Uttamatomakkin. It then traces references to masques and the Banqueting House in colonial writings from Virginia to Barbados to demonstrate the legacy of the banqueting house as a site of civil refinement and place of memory that informed elite Stuart self-fashioning on both sides of the Atlantic.

Introduction

In 1606, as agents of the newly chartered Virginia Company set their sights on Indigenous lands in North America, James VI and I signed off on another project—the building of a new banqueting house to replace the rotting wood and canvas structure that had hosted many court entertainments at Whitehall since 1581. Completed around 1608, this first banqueting house of the king brought the court together for the lavish masques and entertainments that scholars have considered one of the prime artistic innovations of the Jacobean era.1 In 1619, however, a fire broke out, razing the structure to the ground. Despite the strain on Crown finances, James immediately enlisted the architect Inigo Jones to design a replacement, built to the same proportions, over the same foundations. The result was the Banqueting House that survives today, a neoclassical masterpiece so unprecedented in England that it has been deemed unrepresentative of its time, standing at odds with the brick and timber frame structures that characterised Tudor Whitehall. “Banqueting House”, one twentieth-century architectural historian quipped, “is no Jacobean building”.2

1In recent years, scholars of seventeenth-century architecture and dance have established the importance of the two banqueting houses as sites of statecraft and sociability. Per Palme, John Charlton, and Simon Thurley have explored how James’s building projects in Whitehall “formalised the functional division of large ceremonial spaces”, providing an assembly space that was notably larger than any other at court.3 The banqueting houses functioned as a presence chamber, or monarch’s reception room. Additionally, Anne Daye’s assessment of the Banqueting House as a space for dancing, teeming with carpenters and engineers, porters and tumblers, wax and paper props, has brought out its vitality as a performance venue.4 The significance of the Banqueting House for James is clear in its inclusion in what is perhaps the king’s most regal portrait. Commissioned directly by James, Paul van Somer’s painting of 1620 shows the monarch in a strikingly dynamic pose, bearing all the symbols of active sovereign power, and conveying a more opulent side to James’s image-making than is suggested in many of his other portraits (fig. 1). Dressed in red velvet, white silk, and copious ermine, James gazes at the viewer while holding the orb and sceptre. A jewelled imperial crown sits on his head. His multilayered ruff is an extravagant choice of neckwear, even for the time, requiring swathes of lace-edged linen. Significantly, the Banqueting House, in all its harmonious symmetry even before it has actually been completed, fills the composition through the window behind him.

3

Somer’s portrait suggests that the Banqueting House held a special place in the king’s sense of royal patronage and power. Over the course of his reign, James oversaw multiple building projects, including the construction of new Italianate lodgings and galleries at his royal residence in Newmarket; the draining of much of St. James’s Park to expand the gardens and create a menagerie; and the restoration of parts of St. Paul’s Cathedral that had fallen into disrepair.5 While renovating St. Paul’s demonstrated his commitment to ecclesiastical reform, the Banqueting House was James’s more secular project, a visual declaration of his belief in the civilising power of monarchical sovereignty.

5By the time of the portrait, the English had laid claim to territories they called Virginia, Newfoundland, Bermuda (also known as the Somers Isles), and New England, and Indigenous lands and peoples were frequently discussed in Jacobean discourses about imperial authority. This article positions the space of the banqueting house within the context of Atlantic colonialism. If the Banqueting House was intended as a theatre of Stuart sovereignty in this moment of state expansion, how did the Americas come into it? How did the banqueting houses’ specific milieu, and the masques performed within them, inform transatlantic articulations of early Stuart tastes?

The banqueting house’s combined use for occasions of state and refined pleasure set a model for civility that both impacted courtly ideas about the Americas and influenced how travellers framed the way they saw colonial spaces. The following two sections establish how the Banqueting House allowed the king to express multiple civil ideologies in both its facade and its interior, which became a site of colonial encounters. The final section explores several references to masques and James’s banqueting houses in colonial writings in Virginia and the Caribbean to show that the Banqueting House was not only “a memorial to the Stuarts” but also a memorial of Stuart authority and statecraft for English subjects in the colonial Atlantic.6 From the characterisation of an Algonquian guardian spirit dancing under a painted ceiling to visions of Jones’s neoclassical architecture transposed over a Caribbean volcano, James’s two banqueting houses served as landmarks and sites of civil refinement that provided a point of reference and place of memory that informed English self-fashioning on both sides of the Atlantic.

6Building Civility: Whitehall’s Banqueting Houses

Three years after ascending the English throne, James destroyed the makeshift banqueting house that had stood in Whitehall since 1581. This “greate banketyng house”, made from timber columns and canvas, had originally been built to stage performances during Elizabeth I’s diplomatic negotiations with French ambassadors.7 The interior, illuminated with panes of glass, contained canvases painted with coats of arms, clouds, stars, and clusters of fruit, including gold-spangled pomegranates, pumpkins, and cucumbers.8 James dismantled this weathered structure, with its Ionic colonnade of slender, fluted columns, to create a new space for the formal reception of foreign embassies and other state occasions, one that could better accommodate increasingly elaborate plays and masques.9

7In January 1619 a fire burned down the banqueting house. Masques were typically performed in the winter season, and the destruction was fuelled by the highly flammable “oyled painted clothes and pasteboords” and scaffolds that had been assembled for a forthcoming performance.10 James immediately commissioned Inigo Jones to build a new banqueting house in its place. By then, the banqueting house had, with the hall and great chamber, become an indispensable feature of courtly sociability and the articulation of Crown sovereignty, used for the king’s regular addresses to ambassadors and parliament.11 At the same time, the king had long been displeased with its initial design. Inconveniently placed columns prevented a good view of the dances; his “new Favourite, being an excellent Dancer, brought that Pastime into the greater Request”, the writer Arthur Wilson wrote of George Villiers, then earl of Buckingham, in 1617.12

10Jones took no risks with his new design. He made a banqueting house that was fit for purpose—a large ceremonial room with the stately facade of a Venetian palazzo and an interior that invited the viewer to look to the heavens. The building contained an architectural formality that suited the court’s carefully calibrated displays of rank, with the upper and lower ends and its staircases and passageways leading to different parts of the palace. From the reverence paid to the royal family at the end of a masque to the placement of its dais, entrances, and exits, Jones’s Banqueting House made monarchical power both mystical and concrete. A Latin inscription that survives in the State Papers from around 1621, likely intended to appear inside the building, related aesthetic innovation to political grandeur and national prestige. A building once “scarcely made of brick” was now “the equal of any marble buildings throughout Europe”, created for “formal spectacles, and the ceremonials of the British court”.13

13James’s pleasure in watching dances could be accommodated by Jones’s ideas about the “masculine” and “feminine” properties of architecture and their relationship to the public and the private. The exterior was, as Christy Anderson puts it, “the surface that exists in the political world of the city”, related to “contemporary ideas of masculine self-presentation” and stately gravitas (fig. 2).14 Nobility was demonstrated through temperance and “an active control over the emotional and ethical life of the individual”.15 Recognising that columns and their orders were the “essential language” of classical architecture, “the code and marker of the new style of Florence and Rome”, Jones used the upper orders, Ionic (scrolled, fluted columns) and Composite (Ionic/Corinthian, an imperial Roman form), on different storeys.16 The building today has a facade made entirely of Portland stone, but its original contained varying shades: a rusticated golden-brown Oxfordshire stone for the basement, darker Northamptonshire stone for the upper walls, and white Portland stone for the columns, balustrade, and friezes. The “ascending thrust is a symbolic reference to the civilizing benefits of the monarchy”, Anne Daye observes, moving from the more rustic to gleaming moon-white.17

14

For Jones, the majesty of restrained classical architecture relied on a distinction between exterior and interior spaces, between public decorum and the festivities that took place beyond public view. A “graviti in Publique Places”, he acknowledged, did not prevent an interior with “immaginacy set on fire, and sumtimes licentiously flying out”.18 When travelling through Italy with his patron, the collector Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel, Jones jotted notes in his copy of Andrea Palladio’s I quattro libri dell’architettura (1570), taking measurements and inscribing his impressions of the houses he visited. With Banqueting House, he drew on Palladio’s designs for urban palaces and villas, where columns and loggia (or galleries) created multilevel spaces marked by proportion and symmetry. In this vein, Banqueting House is identical on both sides, whether facing the private palace or the public street, maintaining a “calmly dignified facade” that nonetheless left room for the “immaginacy” of interior revelry.19 At the same time, the upper storey’s masks, swags, and scrolled columns, which may have been a concession to the “capricious” ornamentation of Catholic baroque style, brought the inner world of revelry to preside over the highest level of the facade.

18It can be tempting to view the Banqueting House solely as Jones’s project, but the king expressed a keen interest in all stages of its building. As Surveyor of the King’s Works, Jones knew what kind of building would please his patron. Appearing at the entrance to the royal palace, the Banqueting House offered “a kind of manifesto of the newly purely classical style sponsored by the new dynasty from Scotland”, set against the Tudor brick architecture that had dominated Whitehall for so long.20 Models of the building were commissioned, probably so that the designs could be approved by the king and his appointed “Commissioners for the Banqueting House”, including Arundel.21 James went out of his way to view his first new banqueting house after it had been built, and insisted that the second be built quickly, even when Crown finances were scant.22 James encouraged the development of a tapestry works at Mortlake to furnish the interior, and discussed the possibility of commissioning the large ceiling paintings from Peter Paul Rubens as early as 1621, though Rubens’s artworks were installed only some fifteen years later.23

20For some colonial promoters, James’s long-standing architectural interests were a fitting metaphor, and means, for successful expansion. At a sermon at St. Paul’s Cross preached shortly after the completion of the Banqueting House, the geographer and colonial promoter Samuel Purchas celebrated James for his “mature, set[t]led, masculine” kingship, praising that “singular, masculine, reall, regall, absolute” power that conveyed those qualities of rule that were also evident in the architectural precepts of the new Banqueting Hall.24 The king’s authority was grounded in the ownership of land, and even “wide and wilde America, is now new-encompassed with this, with His Crowne”.25 Writing to Prince Charles in 1624, the Scottish courtier William Alexander, earl of Stirling, also recognised James’s reign as a time when “these seeds of Scepters have been first from hence sowne in America”, laying “the foundation of a Worke”. To establish authority in one’s dominions, one must provide “for their Family and Posteritie”—not through quick profiteering schemes such as tobacco plantation, but through “building … that being Owners thereof, [one] will trust it with their maintenance”.26 James’s building projects were an expression of the fixity and durability of the new dynasty on both sides of the Atlantic.

24“He Is Come from a Farre Countrey”: The Banqueting House as a Site of Colonial Encounters

A focus on the dignified classical architecture of the Banqueting House should not distract from the many activities that enlivened it from within. The king’s two banqueting houses were places of sugared confections and “Glorious Scenes”, Ben Jonson wrote, characterised by the ephemerality of costumes and props, flickering candles and colourful assemblages of glue, sparkles, feathers, and paper.27 Although Anna of Denmark has rightfully been credited with evolving masque productions at the Stuart court, James’s cultural interests extended beyond his authorial self-fashioning in print to a patronage of the theatre and court performances.28 Under the arches of the banqueting house stage, performances brought Indigenous Americans and the material culture of the Atlantic into the sociability and diplomatic activities of the English court.

27Several occasions in the first banqueting house contained English encounters with Indigenous peoples—both counterfeit “Indians” and Algonquian travellers. In the 1613–14 masquing season, the gentlemen of Gray’s Inn, with the Attorney General Francis Bacon’s patronage, staged The Maske of Flowers to celebrate the marriage of James’s favourite, Robert Kerr, earl of Somerset, to Lady Frances Howard. The masque was about transformation and restoration where, in a reversal of several stories in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, flowers morphed into human form: “For never Writers pen, / Yet tolde of Flowers return’d to men”.29 The performance began with the Sun ordering Winter and Spring to visit the newlyweds. Spring offered the principal masque. The flower-masquers appeared on a stage decorated with classical columns and fountains, dancing around a globe before transforming into humans. Winter, tasked with the antimasque, presented a spirited challenge between Wine and Tobacco, personified through Silenus, the ruddy, aged guardian of Bacchus, and “Kawasha”, an Algonquian “idol”.

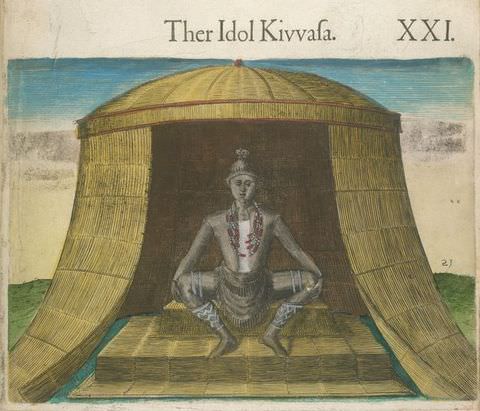

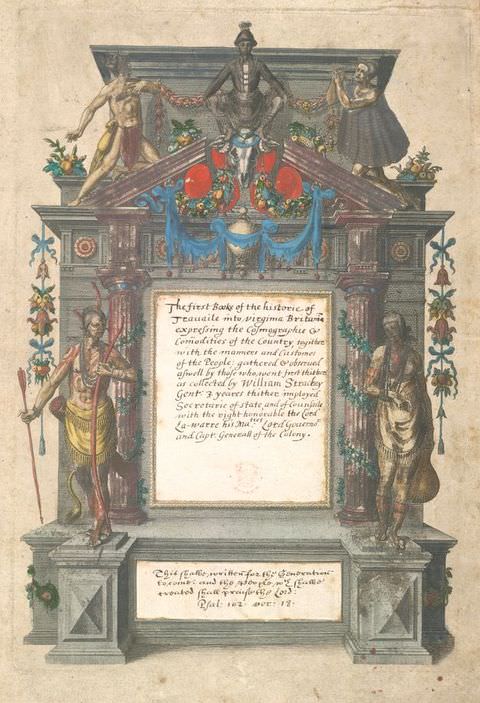

29What inspired Bacon and his collaborators to stage a scene informed by Algonquian culture? At the time, the English used “Virginia” to refer to the lands that stretched from Roanoke, an island off the coast of present-day North Carolina, to the Wampanoag “Dawnland” of what is now New England.30 Kawasha had appeared in Thomas Hariot’s A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, described as “an Idol … carved of woode in lengthe 4. Foote”, wearing white and copper beads, sitting “in the temple of the towne of Secotam [Secotan], as the ke[e]per of the kings dead corpses” (fig. 3).31 Moving between shamans and werowances (political leaders), Kawasha served as an important and fearsome mediator between spiritual and temporal powers: the bodies of deceased rulers were laid by “their Idol Kiwasa … [that] nothinge may hurt them”.32 Having first appeared in the original 1588 edition of Hariot’s text, Kawasha features in the expanded edition of 1590 in one of the images by the Flemish engraver Theodor de Bry, based on the watercolours of the artist and colonist John White. These images were endlessly copied and reprinted in the seventeenth century. They reappeared in the 1610s, when the Jamestown secretary William Strachey incorporated them into various presentation copies of his Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia. Strachey dedicated one copy to Bacon, acknowledging the statesman as a primary supporter of “the Virginia plantation”, though the precise date of Strachey’s copy for Bacon is uncertain.33 In de Bry’s frontispiece, Indigenous figures stand and kneel around a classicised architectural frame, with Kawasha crouching at the top (fig. 4). A Roanoke guardian is transposed to a document about the Chesapeake, as if preparing to leap from the pediment into the masque.

30

In The Maske of Flowers’ antimasque, two temples sat on opposite ends of the stage, one dedicated to Silenus and the other to Kawasha. Kawasha appeared “borne upon two Indians shoulders attired like Floridians”.34 The two “Floridians”, probably based on depictions of the Timucua people, may have involved feathered garments and bodily adornments made of copper or gold alloys, and suggests the ongoing interests of Jacobean colonial promoters in the North American Southwest. In 1609 the geographer Richard Hakluyt had published a promotional tract called Virginia Richly Valued, which described Florida and the gold, silver, and copper mines that might be found in the borderlands of the south. Hakluyt also reported how Thomas Hariot, “a man of much judgement in these causes”, knew of a “rich mine of copper or gold”, “a great melting of red mettall just west of the former colonie of Roanoke”.35

34Although he was known to appear in the spiritual sites of Algonquian homelands as a guardian of the dead, Kawasha’s presence in the Banqueting House equated him with London’s unruly “Roaring boyes” and metropolitan drinking cultures:

36Kawasha comes in majestie,

Was never such a God as he,

He is come from a farre Countrey,

To make our Noses a chimney.36

Silenus and Kawasha leaping around with an oversized tobacco pipe were “contending for superiority”, locked in a battle to assert their intoxicated sovereignty over others. In the end, Kawasha neither vanquished wine nor retreated in defeat. Tobacco was simply a part of sociability at Whitehall, sharing the stage with vines and ancient temples, whether the king liked it or not.

The presence of a Roanoke “idol” and feathered Timucuans were manifestations of English imperial fantasy, serving to bring select aspects of Indigenous cultures into conversation with courtly ideas about nature, civility, and political authority. In The Maske of Flowers, the antimasque was set against the refinement of the main action, where fruitful and ordered gardens were the cultivated antithesis to the “pagan” chaos that had preceded it. The poet and composer Thomas Campion’s contribution to Robert Kerr and Frances Howard’s 1614 nuptials, also a banqueting house masque, involved a “confused” dance by personifications of the four parts of the world: Europe “in the habit of an Empresse”; Asia “in a Persian Ladies habit”; Africa “like a Queene of the Moores”; and “America in a skin coate of the colour of the juyce of Mulberies, on her head large round brims of many coloured feathers”. America appeared as the lesser monarch among the four, possessing only “a small Crowne”.37

37Both The Maske of Flowers and Campion’s untitled marriage masque involved costumes that imparted ideas of racial difference through skin colour, whether through layers of dyed textiles “of Olive-coloured stuff, made close to the skinne” (Kawasha) or “in a skine coate of the colour of the juyce of Mulberies” (America).38 At the season before, in 1613, dozens of feathered “Virginians” came to pay homage to the king in The Memorable Masque, their racial difference similarly marked by “vizerds of olive collour”.39 Scholars have studied extensively the significance of Anna of Denmark darkening her skin to play a “daughter of Niger” in The Masque of Blackness (1605). Such elaborate visual performances served to render black or dark skin as a discernible racial category while simultaneously reinforcing associations of whiteness with purity, or even, in the case of the royal family, quasi-divinity.40 Unlike in The Masque of Blackness or the later Gypsies Metamorphosed (1621), the “Virginians” and “Floridians” were not compelled to transform their allegiances to the English aristocracy by changing their skin colour. Their own powers and sovereignties were set against the civility of other Jacobean dancers, partly for comic effect. There was no sign of the Indigenous capacity or desire to resist English authority, even while this was manifest in the first phase of the Anglo-Powhatan wars in the Chesapeake (1609–14).

38In 1617 Jones and Jonson designed and scripted The Vision of Delight and may have been among those who witnessed the diplomatic reception of the Algonquians who were at court for the occasion. “The Virginia woman Poca-huntas”, John Chamberlain wrote in a letter to the ambassador Dudley Carleton on 18 January 1617, “with her father counsaillor hath ben with the King and graciously used, and both she and her assistant well placed at the maske”.41 In addition to Matoaka, widely known to the English as Pocahontas (a name given to her by her father, Wahunsenaca), Chamberlain referred to her father’s “counsaillor”, Uttamatomakkin (Tomocomo to the English). Uttamatomakkin was a powerful shaman and trusted adviser of the paramount chief. While the Mattaponi oral history of Matoaka’s life discusses how some Powhatan spiritual authorities who crossed the Atlantic adopted different clothes or hairstyles to conceal their identity, Uttamatomakkin operated openly as a shaman, even among the English.42

41E.M. Rose has cautioned against putting too much emphasis on Matoaka’s reception at court, arguing for the Virginia Company’s equally, if not more, important proselytising agenda, which involved efforts to put the Algonquian woman in conversation with merchants, clerics, and members of parliament “in the sphere of religion”.43 If so, her court appearance at the masque was all the more significant, given the banqueting house’s important role in diplomatic affairs. Nonetheless, a great deal of the finer details of protocol and social exchange are lost to time. Chamberlain’s brief reference acknowledges that the king “graciously” accepted Matoaka into the banqueting house, and even that she was “well placed”. Unfortunately, few other details survive to indicate where the Algonquian guests were seated in the hall; how they were treated; what they wore; what honours or gifts they received; or where they had dined beforehand, as was customary before attending the performance and banqueting course. Uttamatomakkin would later complain about a dishonourable reception, unbefitting a dignitary: “your King gave me nothing”.44

43Matoaka’s reception into courtly society had been a concern for the colonist and soldier John Smith in his letter to Anna of Denmark from 1616, when he asked the queen to welcome her and insisted that Matoaka’s status as the daughter of a werowance counted for more than her humble marriage to the planter John Rolfe.45 The portrait engraving made of her during this time acknowledges her status as the daughter of a “king”, and in doing so recognises a Powhatan political territory: Matoaka is recorded as the daughter of the “Emperor of Attanaoughkomouck”, or Tsenacommacah, dressed in fashionable court attire (fig. 5). At the same time, as Karen Robertson has argued, the masque’s “vision of delight” was ultimately a colonial one. While earlier Jacobean masques often moved from “a brutish natural order to the civilities of court”, The Vision of Delight began with a city scene, where “civilization emanates from the urban centre to subsume the whole world”.46 It opened with a “[s]treet in perspective of faire building discovered”, providing the backdrop for the roamings of Delight, Harmony, Grace, Revel, Wonder, and other goddesses.47

45

Through its dreams and “ayrie formes”, the king’s sovereign power began with the grace of the city and its classical architecture, and ended with the glories of cultivation and verdant order. The king was celebrated, in essence, as a patron of plantation, where nature “Do all confesse him; but most These / Who call him lord of the foure Seas”.48 Observing the masque, Matoaka might have witnessed what was, in Robertson’s words, more “a ritual enactment of the processes of power than animated and authorised English settlements on Powhatan land”.49 Though Smith reported that she was well received, the masque did not provoke “ceremonial reshuffling to acknowledge, however tentatively, [Pocahontas’s] presence”.50 The English, after all, had held Matoaka captive in 1613. And, as Smith himself put it, her reception at court was important so that “this Kingdome may rightly have a Kingdome by her meanes”.51 In her public appearances at the masque, as in Simon van de Passe’s portrait, Matoaka remained on display but was unable to speak freely in her own voice, as the Monacan poet Karenne Wood put it.52

48The first banqueting house burned down two years after Matoaka and Uttamatomakkin had watched courtiers celebrate James as commander of “the foure Seas”. The Banqueting House that replaced it emerged as James and his pro-Spanish councillors were in the midst of lengthy contentious negotiations to secure a marriage alliance between Prince Charles and the Infanta Maria Anna, Philip III of Spain’s daughter. The king’s decision to build such a grand structure may well have been a strategic manoeuvre intended to enhance England’s position during these negotiations and provide a powerful setting for diplomatic conversations. For foreign ambassadors, including the ambassadors extraordinary who arrived to negotiate particular and time-sensitive matters of state, the Banqueting House provided the space for their official reception and leave-taking.53

53If part of James’s motivation for building on this unprecedented scale of princely magnificence was to help secure the Spanish match, it was also a strategy to advance English colonialism. An alliance with Spain would profoundly impact English aspirations in the Atlantic, potentially securing “a modus vivendi within the vast Spanish empire agreeable to British commercial interests”.54 But English colonial projects were more diverse and encompassing than that, involving territorial control as well as trade. When he was not overseeing the construction of the Banqueting House, Arundel was busy getting the Amazon Company off the ground.55 By 1620, on Thursdays at two o’clock, courtiers assembled in Arundel’s mansion on the Strand to investigate the possibilities of cultivating yams and cinnamon in South America.56 Arundel hoped that the region would yield “many rich Commodities” from sugar cane to nutmeg, but also “Mines, and Minneralls of sundrye sortes”, in a project endorsed by “many of the nobilitye, and Gentry of this Kingdome”.57 The Spanish ambassador Count Gondomar’s tireless opposition to these projects, however, posed a serious challenge to English aspirations in the Amazon basin.

54Access to the Americas through “Priviledges and Immunities to the English” secured through Prince Charles’s marriage to the Infanta, as one pamphlet explained, would mean that “they shall not digge and delve [in the Indies] as in a barren, desolate, and unfruitfull Quarrie, for nothing but Stones and Rubbidge; But out of most Precious Gold and Silver Mines they shall gather Gold and Silver”.58 The Spanish-English Rose, printed around the time of the Banqueting House’s completion, pitched the English rose and the Spanish pomegranate as emblems of a new Atlantic alliance, just as Alexander the Great, “the Conqueror of the World”, did “Erect his Votive-Altars in the farthest lymits of the Indies, Or that Invincible Hercules his two Pillars”.59 The language of classical monuments, quarries, and conquests suggested a holy alliance created by love and friendship, but understood through an iconography that was often recreated on the masquing stage: triumphal arches, columns, globes, and golden sceptres.

58These projects could have been discussed and furthered in another Banqueting House space: James’s drinking den. The undercroft was turned into a grotto in 1623, when Isaac de Caus, the garden architect and engineer, was charged with “makeing a Rocke in the vaulte under the banquetting house” and furnishing it with “Rocke stuffe, [and] shells”. The following year, de Caus made “an addition of Shellwoorke to the outsyde of the Rocke under the Banquettinge house”.60 Surrounded by a shell grotto that might have reminded its visitors of both Italian garden architecture and the water-themed masques performed on the floor above, the cellar allowed James to host drinking parties in a fantastical and intimate setting.61 The private conversations in this milieu cannot be recovered, but a few of Jonson’s poems of the time, including his dedicatory poem written to bless James’s new cellar, suggests that the Atlantic and European diplomacy were topics of conversation. James came to the cellar to display his liberality and for distraction from his cares, but there was also talk of his conciliarist policies in the midst of the Thirty Years War and of hopes that “with his royall shipping … / Charles brings home the Ladie”.62 In the poem that appears before his dedication to the cellar, Jonson professes no interest in court politics. He cares little for royal matches or those “States Ships sent for belike to meet / Some hopes of Spaine in their West-Indian Fleet”, but he cannot establish his singular commitment to literary pursuits without acknowledging the rumours and whispers of West Indian fleets and Spanish princesses that were part of the most private conversations at the Banqueting House.63

60Through the Arch: Banqueting House Remembered

In 1625 Bacon published an essay titled “Of Masques and Triumphs”, where he declares that such spectacles are “a Thing of great State”, their pleasures lying chiefly in dance, song, costume, scenery, and the glorious “Chariots, wherein the Challengers make their Entry”.64 As Bacon suggests, masques were closely related to classical triumphs, comprising part of the spectacles of elite life, often alluding to the pomp that surrounded victorious emperors returning to Rome with their spoils.65 Arches were widely used in Jacobean masques, as when feathered America processed across the hall towards the stage and throne, through “the lower end of the Hall … [with] an Arch Tryumphall, passing beautifull, which enclosed the whole Workes”.66 Surviving sketches by Jones of temporary arches show how these structures provided a material framework through which revellers entered the domain of the masque (fig. 6). In the choreography of the masque, Daye writes, dancers “passed through the arch from the idealised fantastic world of the scene into the real world of the dancing space and auditorium, just as a monarch passed through a triumphal arch idealising facets of good government into the realities of governance posed by his reign”.67

64

Some colonial writers who travelled to the Americas carried memories of masques and revels with them, as if they too had passed from the arches of the banqueting house stage onto a new scene. John Smith was a soldier who was often critical of what he considered to be the idleness and luxuriousness of elite colonists in the Chesapeake. He accused them of profligacy and incessant complaining about the loss of their “English Cities”, “faire houses”, and “accustomed dainties”.68 At the same time, Smith had written to Anna of Denmark about Matoaka in 1616 and perhaps acted as an intermediary between the Indigenous woman and the court. “Divers Courtiers and others, my acquaintances, hath gone with mee to see her”, he reported, “both publikely at the maskes and otherwise”.69

68Reflecting on his experiences in Tsenacommacah, Smith contrasted the violent wartime “triumphes” that Wahunsenaca made into Werowocomoco, an important spiritual and political site in the Powhatan Confederacy, to the dances and performances that Algonquians staged to entertain the English. He recalled an entertainment from 1608, where Matoaka and some thirty other young Algonquian women emerged from the forest to perform a dance, “onely covered behind and before with a few greene leaves, their bodies all painted”. Smith called the event a “Virginia maske”. His description of horned headpieces and the elements of song and dance mapped courtly choreographies onto the ostensible wilderness of Algonquian homelands. The performers carried props (“severall devices”) such as bows, arrows, and swords, just as goddesses and cupids did in the Banqueting House. The latter might be painted with clouds and stars, but here Smith could look straight up into the heavens.

Smith’s description was intended to be humorous. If it was a masque, it was a topsy-turvy one, full of “hellish shouts and cryes, singing and dauncing with most excellent ill varietie”.70 The occasion offered the inverse, as Elisa Oh writes, of “European court-dance codes in which rigid bodily discipline and geometric formations represented orderly Christian virtues”.71 At the same time, Smith exhibited a sense of the order and practices of masques, with its “severall devices”, and singing and dancing lasting “neare an hour”.72 The event was followed by a torchlit feast. Perhaps most importantly, the masque and ensuing banquet were part of a prolonged power play marked by other diplomatic exchanges and gift giving the following day, conducted on Wahunsenaca’s terms despite English attempts to interpret the events as a relinquishing of Indigenous sovereignty. In framing the events through the masque and its accompanying festivities, Smith both invoked the conventions of court civility and primed his readers to interpret the events in Werowocomoco as high affairs of state.

70By the time Smith published his chronicle of English colonial efforts in 1624, court interests, fuelled by merchants with extensive connections to Atlantic trade and colonial projecting, were expanding into the Caribbean. Anna of Denmark’s queenly successor, Henrietta Maria, supported the cause of a number of puritan elites, including Henry Rich, earl of Holland, who sought to combat Spanish ascendancy in the Caribbean Sea in the late 1620s and early 1630s. The impact of court aesthetics was visible in the writings of travellers to these spaces too. When the colonist Henry Colt travelled to Barbados in the early 1630s, he was preoccupied with the need to construct a “societye” that would replicate life back home. When he arrived, he found an atmosphere of “dayly & violent stormes” that seemed to parallel the “fyery spiritts” of the gentlemen who had arrived on the island to colonise it. Colt knew that building secure physical foundations was key to plantation. The landscape, lacking “Industry”, was all “bushes, & long grasse, all thinges carryinge the face of a desolate & disorderly shew”.73 Houses were difficult to build because palmetto leaves were hard to source. Supplies had to be transported half a mile up a hill, and planters lacked the necessary tools. In the heat of July 1631, Colt recorded his efforts to build cabins and transport goods from shore to plantation. He was chagrined to find his glassware broken in transit. Most depressing of all, “9 great glasse bottles broke of the best Canary wine of England, a losse irrecoverable & lamentable in such a season of sadnesse & misery”. One night Colt dreamed that his friends in England had died.74

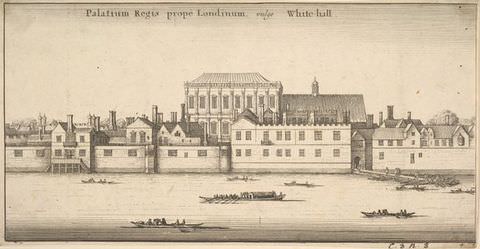

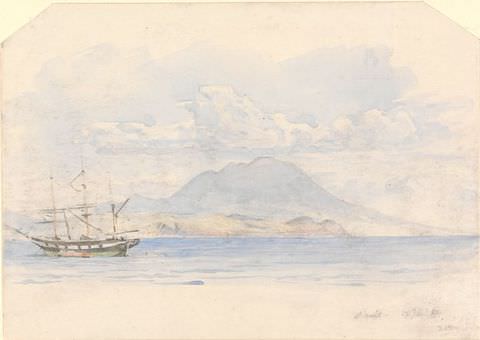

73During that summer, Colt sailed to the volcanic island of Nevis in the Lesser Antilles. When he saw Nevis appear before him, he described its “3. or .4. hills, butt one high above the rest appearinge farr off, like the banquettinge house att Whitehall over the other buyldinges” (figs. 7 and 8).75 For a moment, Colt was not in the Caribbean but near the Thames, aware of the Banqueting House’s predominance in Whitehall. By comparing the craters of Nevis Peak to the Banqueting House, Colt brought the political magnificence and the legibility of the latter to bear on the tropical landscape and to preside over his ideas about building and civility. Colt was in the Caribbean to establish an English presence but also to find “societye”. He grieved the loss of glasses and wine bottles, which offered a connection to the leisurely pursuits and masculine friendships enjoyed by gentlemen at home. Had the islands been “seated in any part of Europe”, Colt admitted, he would be fighting off “the princes of Europe [who] by force or covetousnesse would not take [them] from me”.76

75

Some fifteen years later, the royalist sugar planter Richard Ligon travelled to Barbados. By 1645, an estimated 5,680 enslaved people were working on its plantations, predominantly Africans and people with African heritage but also Arawaks and Kalinago (Carib), as well as white labourers, many of them political prisoners from the civil wars.77 Ligon’s account demonstrated his awareness of the role of enslaved people in sugar production, as well as the dangers and caprices of a society ruled by wealthy landowners who feared social unrest at all levels of society.78 Like Colt, he viewed the mountainous Leeward Islands as “large buildings”, and Barbados’s plantations as pleasingly tiered along the coast, “like severall stories in stately buildings, which afforded us a large proportion of delight”.79

77Colt’s and Ligon’s texts offer examples of how their memory of the court, and of early Stuart articulations of imperial sovereignty through masques and architecture, shaped their views of the Atlantic landscapes and societies they moved through. On his way to Barbados, Ligon stopped in St. Jago (Santiago), where he was enraptured by the governor Padre Vagado’s “black mistresse”, whom he described as possessing “far greater majesty, and gracefulness, then I have seen Queen Anne, descend from the Chaire of State … at a Maske in the Banquetting House”.80 The comparison seems eccentric at first, even subversive: Anna of Denmark is evoked, descending from the throne, to demonstrate the grace of an unnamed woman “of the greatest beautie and majestie”, wearing silk, ribbons, and pearls, her head adorned with a roll of green taffeta.81 But perhaps Jacobean masques had quite literally set the stage for interpreting colonial encounters in this way. Anna of Denmark, after all, had painted her skin black for The Masque of Blackness, and she and her ladies frequently appeared in sea-green silks and sky-blue mantles in their roles as nymphs and sea-goddesses in Tethys Festival (1610) and elsewhere. A surviving portrait miniature by Isaac Oliver from 1610, depicting the queen in classical antique profile, masquing costume, and swathes of pearls, captures such fashions (fig. 9). Such representations of masquing women, with their fair beauty and fantastical costumes, may have been on Ligon’s mind when he likened the African woman’s teeth to “rowes of pearls, so clean, white, Orient, and well shaped, as Neptunes Court was never pav’d with such as these”.82

80

Despite differences in Smith’s, Colt’s, and Ligon’s social backgrounds, masques and banqueting houses provided a recognisable point of reference for their audiences back home. Their readers were women and men who were familiar with the aesthetics and significance of masques and the confections that accompanied them. His “rude military hand”, Smith professed to Frances Stewart, duchess of Richmond and Lennox, cut rough “Paper Ornaments”, but he had been “a reall Actor”, thrust into the field of conquest like Caesar, on the hunt for “chests of Sugar” and “Boats [loaded] of Sugar, Marmelade, [and] Suckets”.83 These writers used the Banqueting House and the memory of its performances not only to demonstrate their own refined sensibilities, but also to show the difficulties of enacting princely models of civility so far from the court. For Colt, the Banqueting House was a landmark. But if it was a stand-in for Whitehall, it was an elusive one, appearing and vanishing before him, reminding him that he was far from home—palaces “melted into air”, an “insubstantial pageant faded”, as Shakespeare’s Prospero would declare, interrupting his own colonial masque.84

83Conclusion: Naumkeag Marble and Smoky Rooms

In 1625 the Scottish planter David Thomson wrote a letter to Arundel from Massachusetts, enquiring as to whether the earl had received the “graye marble I found in this countrie neere to Naemkeek [Naumkeag]”. He had also seen “a Tobacco pype of a transparent stone lykest in my simple judgem[en]t to pure whyte Alabaster”: “I enquyred the Salvage that had it, where he had it, he told me at Poconoakit, and that there was much of that sort”.85 It seems likely that Thomson provided details about possible sources of marble and alabaster because of his patron’s interests in building and collecting. For years, Arundel had served on the committee for James’s new Banqueting House. He had seen the prodigious operations that brought stone from the Isle of Portland to create the decorative features of its grand facade. But, even as the emulation and innovation of classical styles changed the topography of London, materials from the Americas were also finding their way in.

85Aristocratic interests in monumental building extended across the Atlantic. James’s willingness to break with Tudor architecture styles, and the classical precepts that underpinned the Banqueting House’s facade, may have played a role in how colonists visually expressed English imperial authority in colonial spaces such as Virginia and Bermuda, whose Italianate State House was built in 1620.86 In the 1630s and 1640s, estate houses in the Chesapeake and Barbados brought banqueting houses and classical-style architecture to English plantations, offering some of the “largest, most complicated man-made structures” in the British Atlantic.87

86Just as important as its facade was the function of its interior. Within the banqueting houses, Anglo-Spanish competition in the Atlantic, Algonquian politics, and social concerns about tobacco became part of Stuart court culture. Rather than pitching James’s perceived lack of artistic patronage against Anna of Denmark’s, the legacy of the banqueting houses shows how the eclectic cultural world of the court, with its masques, imperial imagery, and new architectural styles, contributed to subjects’ colonial aspirations and associations with empire. Imperial fantasies were brought to life through distinct spaces and the dance, music, and sugared banquets they contained. Triumphant sea gods and feathered personifications of America played a role in how the Jacobean elite, busy planning and financing colonial ventures, viewed their own place in the project of expansion. When James commissioned a portrait of himself in his most regal attire, with the Banqueting House behind him, he was establishing himself as a magnificent architectural patron, but he may also have been relating his authority to the negotiations and alliances that happened in its interior.

From his denunciation of smoking in A Counterblaste to Tobacco, James had always been concerned with protecting the purity of the commonwealth from what he viewed as the dangerously intoxicating influence of Indigenous practices.88 Evidence survives of the king ordering tobacco houses near his residences and procession routes to be demolished, including two brick houses near the court at Theobalds in 1618, and several near the west gate of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1620.89 But, even as James sought to eradicate the plant and the social spaces that grew up around it, tobacco and other matter from the Americas permeated Whitehall, bringing materials extracted from Indigenous homelands into the glittering, smoky atmosphere of the masque. In The Fortunate Isles and Their Union (1625), the last masque acted for James before his death, medieval English poets and a melancholy student shared the stage with a cohort of sea gods. The masque’s dazzling centrepiece was a floating, mobile island, prompting songs about Neptune’s power and “his Fleete, ready to goe or come, / Or fetch the riches of the Ocean home”, where “both at Sea, and Land, our powers increase”.90 These goods included “the greener Emerald”, a precious stone excavated almost exclusively from the Muzo and Muisca territories of what is now Colombia (fig. 10). Emeralds appeared on courtiers’ bodies in pendants, earrings, necklaces, and watches—in the case below, completely encircling the royal court of arms in its distinctive blue-green flash (fig. 11). In the world of the masque, the way the airy spirit Johphiel introduced one Old English character to this new modern age was to allude to the colonial world beyond the pillars of the stage: “we can mix him with moderne Vapors, / The Child of Tobacco, his pipes, and his papers”.91

88

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editors of the “Reframing King James VI and I” special issue, Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray, for their direction and support. My thinking around the piece was much enhanced by the conversations and questions offered by fellow participants at the associated Paul Mellon Centre workshop on 29 July 2024. I am immensely grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the British Art Studies editorial team for their guidance, encouragement, and feedback.

About the author

-

Lauren Working is Lecturer in Early Modern Literature at the University of York. Her research focuses on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literary sociability, material culture, and colonialism. Her publications include The Making of an Imperial Polity: Civility and America in the Jacobean Metropolis (Cambridge University Press, 2020), the co-authored Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England (Amsterdam University Press, 2021), and articles on intoxicants, Counter-Reformation women and architectural patronage, the Inns of Court, and the colonial gaze in a cavalier poem about Madagascar. Her new introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Shakespeare’s The Tempest was published in 2024.

Footnotes

-

1

Martin Butler, The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Barbara Ravelhofer, The Early Stuart Masque: Dance, Costume, and Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Clare McManus, Women on the Renaissance Stage: Anna of Denmarkand Female Masquing in the Stuart Court (1590–1619) (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002); John H. Astington, “The Jacobean Banqueting House as a Performance Space”, in Performances at Court in the Age of Shakespeare, ed. Sophie Chiari and John Mucciolo (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 203–20. ↩︎

-

2

Marcus Whiffen, An Introduction to Elizabethan and Jacobean Architecture (London: Art and Technics, 1952), 44, quoted in Per Palme, Triumph of Peace: A Study of the Whitehall Banqueting House (London: Thames & Hudson, 1957), xv. ↩︎

-

3

Simon Thurley, Whitehall Palace: An Architectural History of the Royal Apartments, 1240–1690 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 82. ↩︎

-

4

Anne Daye, “The Banqueting House, Whitehall: A Site Specific to Dance”, Historical Dance 4 (2004): 3–22. ↩︎

-

5

John Harris, “Inigo Jones and the Prince’s Lodging at Newmarket”, Architectural History 2 (1959): 26–40; John Charlton, The Banqueting House Whitehall (London: HMSO, 1964); John Harris, Stephen Orgel, and Roy Strong, The King’s Arcadia: Inigo Jones and the Stuart Court (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1973). ↩︎

-

6

Charlton, The Banqueting House, 7. ↩︎

-

7

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 115. ↩︎

-

8

Charlton, The Banqueting House, 11. ↩︎

-

9

Charlton, The Banqueting House, 11–12. See also McManus, Women on the Renaissance Stage. ↩︎

-

10

The Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 2, ed. N. E. McClure (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939), 202, quoted in Palme, Triumph of Peace, 1–2. ↩︎

-

11

Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 5; “Abstract of the King’s Speech in the Banqueting Chamber”, 21 March 1610, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, SP 14/53, fol. 43; John Chamberlain to Dudley Carleton, 14 April 1614, TNA, SP 14/77, fol. 9. ↩︎

-

12

Arthur Wilson, The History of Great Britain, Being the Life and Reign of King James the First (London: Richard Lownds, 1653), 104, quoted in Jean MacIntyre, “Buckingham the Masquer”, Renaissance and Reformation 22 (1998): 60. ↩︎

-

13

Gregory Martin, Rubens in London: Art and Diplomacy (London: Harvey Miller, 2011), 30. ↩︎

-

14

Christy Anderson, Inigo Jones and the Classical Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 151. ↩︎

-

15

Anderson, Inigo Jones and the Classical Tradition, 153. ↩︎

-

16

Anderson, Inigo Jones and the Classical Tradition, 130. ↩︎

-

17

Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 6. Aaron White has related Jones’s use of whiteness to convey civility in architecture to race making in masques. Aaron White, “‘To Blanch an Aethiop’: Inigo Jones, Queen Anna, and the Staging of Whiteness”, in Early Modern Architecture and Whiteness: Power by Design, ed. Dijana Omeragić Apostolski and Aaron White (New York: Routledge, 2025), 75–96. ↩︎

-

18

Inigo Jones, Roman Sketchbook [circa 1614], fol. 76v, Chatsworth House, quoted in Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 10. ↩︎

-

19

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 35. ↩︎

-

20

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 21. On the possible influence of James’s Scottish heritage on his first banqueting house, see Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 11. ↩︎

-

21

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 3. ↩︎

-

22

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 3. See also Jemma Field, “‘Orderinge Things accordinge to His Majesties Comaundment’: The Funeral of the Stuart Queen Consort Anna of Denmark”, Women’s History Review 30 (2021): 835–55. ↩︎

-

23

John Chamberlain to Dudley Carleton, August 1619, in Letters, 2:260, quoted in Palme, Triumph of Peace, 26. ↩︎

-

24

Samuel Purchas, The Kings Towre (London: W. Stansby, 1622), 55, 58–59. ↩︎

-

25

Purchas, The Kings Towre, 66–67. ↩︎

-

26

William Alexander, An Encouragement to Colonies (London: W. Stansby, 1624), “Epistle Dedicatorie”. ↩︎

-

27

Ben Jonson, “An Epistle Answering to One that Asked to Be Sealed of the Tribe of BEN”, in The Workes of Benjamin Jonson (London: J. Beale, J. Dawson, B. Alsop, and T. Fawcet for R. Meighen [and T. Walkley], 1641), 218. ↩︎

-

28

Jane Rickard, Writing the Monarch in Jacobean England: Jonson, Donne, Shakespeare and the Works of King James (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 49–50. ↩︎

-

29

John Coperario, The Maske of Flowers (London: N.O. for Robert Wilson, 1614), C2v. ↩︎

-

30

On the impact of colonialism on the inhabitants of Dawnland, see Siobhan Senier, ed., Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014). ↩︎

-

31

Thomas Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (Frankfurt: J. Wecheli, 1590), 63. ↩︎

-

32

“Ther Idol Kiwasa”, in Hariot, A Briefe and True Report, n.p. ↩︎

-

33

William Strachey, The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia Expressing the Cosmographie and Comodities of the Country [circa 1612?], British Library, Sloane MS 1622, fol. 2. ↩︎

-

34

The Maske of Flowers, B3r. ↩︎

-

35

Richard Hakluyt, Virginia Richly Valued (London: F. Kyngston for M. Lownes, 1609), A2v. ↩︎

-

36

The Maske of Flowers, B4r. ↩︎

-

37

Thomas Campion, The Description of a Maske: Presented in the Banqueting Roome at Whitehall (London: E.A. for Laurence Li’sle, 1614), Br. ↩︎

-

38

Campion, The Description of a Maske, B2r. ↩︎

-

39

Karen Kupperman, Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000), 58–59; George Chapman, The Memorable Maske (London, G. Eld for G. Norton, 1613). ↩︎

-

40

Kim Hall, Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995); Noémie Ndiaye, Scripts of Blackness: Early Modern Performance Culture and the Making of Race (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022); “Blackamoor”, in Nandini Das et al., Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), 40–50; Tracey Hill, Pageantry and Power: A Cultural History of the Early Modern Lord Mayor’s Show, 1585–1639 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011); Sujata Iyengar, Shades of Difference: Mythologies of Skin Color in Early Modern England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005). See also Mia Bagneris, “Painting the Queen Black”, British Art Studies 29 (2025), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/mbagneris. ↩︎

-

41

John Chamberlain to Dudley Carleton, 18 January 1617, The National Archives, SP 14/90/25, fol. 56, quoted in Karen Robertson, “Pocahontas at the Masque”, Signs 21 (1996): 552. ↩︎

-

42

Linwood “Little Bear” Custalow and Angela “Silver Star” Daniel, The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History (Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2007), 75. On Matoaka’s different names and personas, see Kathryn N. Gray and Amy M.E. Morris, eds., Matoaka, Pocahontas, Rebecca: Her Atlantic Identities and Afterlives (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2024). Although “Pocahontas” is used by many Indigenous scholars and writers, others prefer “Matoaka” or use the names for different aspects of her life story. This article uses Matoaka in part to centre her presence in the Banqueting House beyond the colonial fantasies that became wrapped up in the English use of the name “Pocahontas” during this visit, but also because it is the sole Indigenous name that appears on the courtly portrait discussed here. ↩︎

-

43

E.M. Rose, “Pocahontas’ Trip to England: The View from London, 1616–1617”, in Matoaka, Pocahontas, Rebecca, ed. Gray and Morris, 118. ↩︎

-

44

John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (London: J. Dawson and J. Haviland for M. Sparkes, 1624), 123. ↩︎

-

45

Smith, Generall Historie, 121–23. ↩︎

-

46

Robertson, “Pocahontas at the Masque”, 553. ↩︎

-

47

Jonson, The Vision of Delight, in The Workes of Benjamin Jonson, 18. ↩︎

-

48

Jonson, The Vision of Delight, 21. ↩︎

-

49

Robertson, “Pocahontas at the Masque”, 553. ↩︎

-

50

Robertson, “Pocahontas at the Masque”, 552. ↩︎

-

51

Smith, Generall Historie, 122. ↩︎

-

52

Karenne Wood, in Kathryn N. Gray and Amy M.E. Morris, “Introduction”, in Matoaka, Pocahontas, Rebecca, ed. Gray and Morris, 8. ↩︎

-

53

Martin, Rubens in London, 30. ↩︎

-

54

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 12. ↩︎

-

55

Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 10. ↩︎

-

56

Joyce Lorimer, ed., English and Irish Settlement on the River Amazon, 1560-1646 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1989), 181, 192–98. ↩︎

-

57

Lorimer, English and Irish Settlement, 193. ↩︎

-

58

Michael du Val, Rosa Hispani-Anglica [The Spanish-English Rose] (London: London: Eliot’s Court Press, 1622), 27. ↩︎

-

59

Du Val, Rosa Hispani-Anglica, 80. ↩︎

-

60

Palme, Triumph of Peace, 66. ↩︎

-

61

Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 5. ↩︎

-

62

Ben Jonson, “The Dedication of the Kings New Cellar. To Bacchus”, in The Workes of Benjamin Jonson, 220. ↩︎

-

63

“An Epistle answering to one that asked to be Sealed of the Tribe of BEN”, in The Workes of Benjamin Jonson, 218. ↩︎

-

64

Francis Bacon, “Of Masques and Triumphs”, in The Essayes or Counsels, Civil and Morall, of Francis Lo[rd] Verulam (London: J. Haviland, 1625), 223–26. ↩︎

-

65

See “Triumph”, n., 1.a., in Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/triumph_n?tab=meaning_and_use#17614749. ↩︎

-

66

Campion, The Description of a Maske, A2v. ↩︎

-

67

Daye, “The Banqueting House”, 16. ↩︎

-

68

Smith, The Generall Historie, 39. ↩︎

-

69

Smith, The Generall Historie, 123. ↩︎

-

70

Smith, The Generall Historie, 67. ↩︎

-

71

Elisa Oh, “Advance and Retreat: Reading English Colonial Choreographies of Pocahontas”, in Travel and Travail: Early Modern Women, English Drama, and the Wider World, ed. Patricia Akhimie and Bernadette Andrea (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 124. ↩︎

-

72

Oh, “Advance and Retreat”, 124. ↩︎

-

73

Henry Colt, “The Voyage of Henry Colt”, in Colonising Expeditions to the West Indies and Guiana, 1623–1667, ed. Vincent T. Harlow (London: Hakluyt Society, 1925), 66–67. ↩︎

-

74

Colt, “Voyage”, 90–91, 82. ↩︎

-

75

Colt, “Voyage”, 84. ↩︎

-

76

Colt, “Voyage”, 69. ↩︎

-

77

Susan Scott Parrish, “Richard Ligon and the Atlantic Science of Commonwealths”, William and Mary Quarterly 67 (2010): 225. ↩︎

-

78

Parrish, “Richard Ligon and the Atlantic Science of Commonwealths”, 226–27. ↩︎

-

79

Richard Ligon, A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados (London: H. Moseley, 1657), 21. ↩︎

-

80

Ligon, A True and Exact History, 13. ↩︎

-

81

Ligon, A True and Exact History, 13. ↩︎

-

82

Ligon, A True and Exact History, 13. ↩︎

-

83

Smith, The Generall Historie, unpaginated and 224. ↩︎

-

84

William Shakespeare, The Tempest, 4.1.155. ↩︎

-

85

David Thomson to the Earl of Arundel, 1 July 1625, in The Life, Correspondence, and Collections of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, ed. Mary F.S. Hervey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 502. ↩︎

-

86

Brent Fortenberry and Jenna Carlson, “Fare for Empire: Commensal Events in Colonial Bermuda”, International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 19 (2015): 574. ↩︎

-

87

Cary Carson, “Banqueting Houses and the ‘Need for Society’ among Slave-Owning Planters in the Chesapeake Colonies”, William & Mary Quarterly 70 (2013): 727; Robert Tavernor, Palladio and Palladianism (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991). ↩︎

-

88

James I, A Counterblaste to Tobacco (London: R. Barker, 1604), C4v, Cr. ↩︎

-

89

John Wolley to William Trumbull, 24 September 1618, in G. Dyfnallt Owen and Sonia P. Anderson, ed., Report on the Manuscripts of the Most Honourable the Marquess of Downshire, vol. 6 (London: HMSO, 1995), 521; “A letter to the Lord Bishop of London and the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedrall Church of St Paule”, 23 March 1620, TNA, PC 2/30. ↩︎

-

90

The Fortunate Isles and Their Union, in The Workes of Benjamin Jonson, 143, 117. ↩︎

-

91

The Fortunate Isles and Their Union, 137. ↩︎

Bibliography

“Abstract of the King’s Speech in the Banqueting Chamber”. 21 March 1610. The National Archives, Kew, SP 14/53.

Alexander, William. An Encouragement to Colonies. London: W. Stansby, 1624.

Anderson, Christy. Inigo Jones and the Classical Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Astington, John H. “The Jacobean Banqueting House as a Performance Space”. In Performances at Court in the Age of Shakespeare, edited by Sophie Chiari and John Mucciolo, 203–20. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Bacon, Francis. The Essayes or Counsels, Civil and Morall, of Francis Lo[rd] Verulam. London: J. Haviland, 1625.

Butler, Martin. The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Campion, Thomas. The Description of a Maske: Presented in the Banqueting Roome at Whitehall. London: E.A. for Laurence Li’sle, 1614.

Carson, Cary. “Banqueting Houses and the ‘Need for Society’ among Slave-Owning Planters in the Chesapeake Colonies”. William & Mary Quarterly 70 (2013): 725–80. DOI:10.5309/willmaryquar.70.4.0725.

Chamberlain, John, to Dudley Carleton. 14 April 1614. The National Archives, Kew, SP 14/77.

Chamberlain, John. The Letters of John Chamberlain. Vol. 2. Edited by N.E. McClure. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939.

Chapman, George. The Memorable Maske. London: G. Eld, for G. Norton, 1613.

Charlton, John. The Banqueting House Whitehall. London: HMSO, 1964.

Colt, Henry. “The Voyage of Henry Colt”. In Colonising Expeditions to the West Indies and Guiana, 1623–1667, edited by Vincent T. Harlow, 54–102. London: Hakluyt Society, 1925.

Coperario, John. The Maske of Flowers. London: N.O. for Robert Wilson, 1614.

Custalow, Linwood “Little Bear”, and Angela “Silver Star” Daniel. The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2007.

Das, Nandini, Joāo Melo, Haig Smith, and Lauren Working. Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

Daye, Anne. “The Banqueting House, Whitehall: A Site Specific to Dance”. Historical Dance 4 (2004): 3–22.

du Val, Michael. Rosa Hispani-Anglica. London: Eliot’s Court Press, 1622.

Field, Jemma. Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Field, Jemma. “‘Orderinge Things accordinge to His Majesties Comaundment’: The Funeral of the Stuart Queen Consort Anna of Denmark”. Women’s History Review 30 (2021): 835–55. DOI:10.1080/09612025.2020.1827730.

Fortenberry, Brent, and Jenna Carlson. “Fare for Empire: Commensal Events in Colonial Bermuda”. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 19 (2015): 568–600. DOI:10.1007/s10761-015-0299-0.

Gray, Kathryn N., and Amy M.E. Morris. “Introduction”. In Matoaka, Pocahontas, Rebecca: Her Atlantic Identities and Afterlives, edited by Kathryn N. Gray and Amy M.E. Morris, 1–18. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2024.

Gray, Kathryn N., and Amy M.E. Morris. Matoaka, Pocahontas, Rebecca: Her Atlantic Identities and Afterlives. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2024.

Hakluyt, Richard. Virginia Richly Valued. London: F. Kyngston for M. Lownes, 1609.

Hall, Kim. Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Hariot, Thomas. A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia. Frankfurt: J. Wecheli, 1590.

Harlow, Vincent T., ed. Coloniszing Expeditions to the West Indies and Guiana, 1623–1667. London: Hakluyt Society, 1925.

Harris, John. “Inigo Jones and the Prince’s Lodging at Newmarket”. Architectural History 2 (1959): 26–40. DOI:10.2307/1568218.

Harris, John, Stephen Orgel, and Roy Strong. The King’s Arcadia: Inigo Jones and the Stuart Court. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1973.

Hill, Tracey. Pageantry and Power: A Cultural History of the Early Modern Lord Mayor’s Show, 1585–1639. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011.

Howard, Thomas. The Life, Correspondence, and Collections of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel. Edited by Mary F.S. Hervey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Iyengar, Sujata. Shades of Difference: Mythologies of Skin Color in Early Modern England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

James I. A Counterblaste to Tobacco. London: R. Barker, 1604.

Jones, Inigo. Roman Sketchbook. [Circa 1614.] Chatsworth House.

Jonson, Ben. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. London: J. Beale, J. Dawson, B. Alsop, and T. Fawcet for R. Meighen [and T. Walkley], 1641.

Kupperman, Karen. Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

“A Letter to the Lord Bishop of London and the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedrall Church of St Paule”. 23 March 1620. The National Archives, Kew, PC 2/30.

Ligon, Richard. A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbados. London: H. Moseley, 1657.

Lorimer, Joyce, ed. English and Irish Settlement of the River Amazon. London: Hakluyt Society, 1989.

MacIntyre, Jean. “Buckingham the Masquer”. Renaissance and Reformation 22 (1998): 59–81. DOI:10.33137/rr.v34i3.10817.

Mann, Emily. “Two Islands, Many Forts: Ireland and Bermuda in 1624”. In Ireland, Slavery, and the Caribbean: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Finola O’Kane and Ciaran O’Neill, 215–39. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022. DOI:10.7765/9781526151001.00023.

Martin, Gregory. Rubens in London: Art and Diplomacy. London: Harvey Miller, 2011.

McManus, Clare. Women on the Renaissance Stage: Anna of Denmark and Female Masquing in the Stuart Court (1590–1619). Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.

Ndiaye, Noémie. Scripts of Blackness: Early Modern Performance Culture and the Making of Race. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022.

Oh, Elisa. “Advance and Retreat: Reading English Colonial Choreographies of Pocahontas”. In Travel and Travail: Early Modern Women, English Drama, and the Wider World, edited by Patricia Akhimie and Bernadette Andrea, 139–57. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

Owen, G. Dyfnallt, and Sonia P. Anderson, eds. Report of the Manuscripts of the Most Honourable the Marquess of Cownshire. Vol. 6. London: HMSO, 1995.

Palme, Per. Triumph of Peace: A Study of the Whitehall Banqueting House. London: Thames & Hudson, 1957.

Parrish, Susan Scott. “Richard Ligon and the Atlantic Science of Commonwealths”. William and Mary Quarterly 67 (2010): 209–48. DOI:10.5309/willmaryquar.67.2.209.

Purchas, Samuel. The Kings Towre. London: W. Stansby, 1622.

Ravelhofer, Barbara. The Early Stuart Masque: Dance, Costume, and Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Rickard, Jane. Writing the Monarch in Jacobean England: Jonson, Donne, Shakespeare and the Works of King James. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Robertson, Karen. “Pocahontas at the Masque”. Signs 21 (1996): 551–83. DOI:10.1086/495098.

Rose, E.M. “Pocahontas’ Trip to England: The View from London, 1616–1617”. In Matoaka, Pocahontas, Rebecca: Her Atlantic Identities and Afterlives, edited by Kathryn N. Gray and Amy M.E. Morris, 115–50. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2024.

Senier, Siobhan, ed. Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Smith, John. The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles. London: J. Dawson and J. Haviland for M. Sparkes, 1624.

Strachey, William. The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia Expressing the Cosmographie and Comodities of the Country. [Circa 1612?] British Library, Sloane MS 1622.

Tavernor, Robert. Palladio and Palladianism. London: Thames & Hudson, 1991.

Thurley, Simon. Whitehall Palace: An Architectural History of the Royal Apartments, 1240–1690. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999.

Whiffen, Marcus. An Introduction to Elizabethan and Jacobean Architecture. London: Art and Technics, 1952.

White, Aaron. “‘To Blanch an Aethiop’: Inigo Jones, Queen Anna, and the Staging of Whiteness”. In Early Modern Architecture and Whiteness: Power by Design, edited by Dijana Omeragić Apostolski and Aaron White, 75–96. New York: Routledge, 2025.

Wilson, Arthur. The History of Great Britain, Being the Life and Reign of King James the First. London: Richard Lownds, 1653.

Working, Lauren. The Making of an Imperial Polity: Civility and America in the Jacobean Metropolis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/lworking |

| Cite as | Working, Lauren. “James VI and I’s Banqueting Houses: A Transatlantic Perspective.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/lworking. |