Limnings of James VI and I and the Jacobean World in Alba Amicorum

Limnings of James VI and I and the Jacobean World in Alba Amicorum

By Sophie Ninetta Rhodes

Abstract

Limning is an art form traditionally associated with early modern portrait miniature painting. However, the term was used contemporaneously to describe a more extensive range of watercolour-based art forms, including botanical illustrations, heraldry, and landscapes. One type of limning can be found in the alba amicorum (meaning “friendship albums” or “books of friends”) of travellers to London in the early seventeenth century. This article explores the German soldier Michael van Meer’s album, which contains an extensive array of unusual and vivid limnings that capture aspects of the Jacobean court and include likenesses of James VI and I and Anna of Denmark. After considering the technical and theoretical relationship between alba limnings produced in London and other forms of limning, it then demonstrates how the limned illustrations of Jacobean London shed light on the dissemination of royal and courtly images and, in their depictions of James and Anna in public settings, project a sense of royal visibility and accessibility. Viewed as limnings, these alba illustrations reveal how English visual culture intersected with the northern European album amicorum tradition.

Introduction

The term “limning” derives from the Latin luminare, meaning “to illuminate”, and was historically associated with manuscript illumination: the application of water-soluble paint and gold on vellum or paper. Art historians have usually associated the term exclusively with portrait miniature painting, but sixteenth- and seventeenth-century accounts reveal that the term encompassed a wide array of objects.

The two most significant sources for understanding late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century limning are the herald and musician Edward Norgate’s treatise Miniatura, or, The Art of Limning, initially written in 1627–28 and redrafted in late 1648, and Nicholas Hilliard’s The Art of Limning from around 1600.1 As Norgate explained in the opening paragraph of his manuscript, his text applied not only to portrait miniature painting, for limning was a technique “as well for Picture by the Life, as for Lanscape History Armes Flowers &c.”.2 Norgate was not alone in this interpretation of “limning”. In The Compleat Gentleman, Henry Peacham expanded on the “manifold uses of … limning”, in which he included maps, botanical and biological illustrations, coats of arms, portraits, and more.3 Limning was evidently an art form that encompassed myriad genres.

1Scholarly studies of limning in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century England rarely consider objects apart from miniatures. John White’s watercolours of the Algonquian peoples in Virginia, which depict their customs, flora, fauna, and landscapes, are an exception here; recent scholarship has on occasion aligned these rare watercolours with Elizabethan limning.4 Instead of applying the term exclusively to portrait miniature painting, these studies define limning “as a watercolour art, different from oil, as adjunct to drawing”.5 A contemporaneous genre of limnings, which has never been discussed in relation to other types of limning, is the watercolour illustrations of King James VI and I and of Jacobean London found in various alba amicorum of continental travellers to London. These limnings appear to have been painted directly into traveller’s albums by an artist (or more likely a workshop); on occasion they may have been copied by the owner of the album himself using an artist’s or workshop’s prototype. Very similar limnings are found in various albums, which suggests that there was a market for these objects in London and that one artist or workshop might have been responsible for the different versions. Examples of these linings are occasionally found outside alba amicorum.6 However, given that most of the surviving examples are in these albums, I shall refer to them as “alba limnings”.

4Alba amicorum (meaning “friendship albums” or “books of friends”) emerged in Protestant academic circles in Germany in the 1540s.7 The practice originated with university students asking famous Protestant Reformers and teachers to sign their names in the margins of their Bibles, but it quickly developed into a genre in its own right. Alba amicorum spread to other northern European countries and bridged the confessional divide.8 Using pre-bound blank albums or interweaving blank pages into printed texts or albums of allegorical prints, owners—who soon extended beyond the university sphere—gathered the signatures of friends and notable people they met on their travels.9 Alba soon contained not just signatures but also mottoes and humanist inscriptions, pasted-in prints and watercolour illustrations. Most of the alba that survive today were made by men, and can be viewed in the context of humanist male friendships. Alba often also contain the signatures of monarchs. The albums therefore had an aspirational element, serving as a means of self-fashioning and self-promotion for their owners.10 In recent years, scholars have increasingly turned their attention to alba amicorum, exploring, for example, notions of friendship and networks, their materiality, and the text found within the albums.11

7A particularly important source is the album compiled by the German soldier Michael van Meer, who visited London in 1614–15.12 Described by June Schlueter as being “exceptional for the abundance and opulence of its illustrations”, this album is an often overlooked insight into King James and the Jacobean period.13 As with other alba featuring watercolour illustrations, the pages containing these works are generally unsigned and were probably acquired by their owners to illustrate their travels. Comparisons have been drawn to modern-day collections of postcards.14 James’s reign in England seems to have been a particularly prolific period for the production of this type of watercolour in London. Similar illustrations are preserved in the albums of several other visitors to the city during this period, among them Jacob Fetzer, Frederic de Botnia, Tobias Oelhafen von Schöllenbach, Georg Holzschuher von Neuenbürg, and Giese Raban. De Botnia’s profession remains uncertain, but the other figures were students from German cities, all of whom travelled to London between 1610 and 1625.15

12One of the many questions that has plagued alba amicorum scholars is how to categorise these objects. Sophie Reinders and Jeroen Vandommele suggest that, historically, alba have been used to address subject-specific questions, with the result that the “best bits” of various albums have been highlighted rather than the albums being assessed as a whole.16 One obvious issue with categorising the alba is that they draw from a disparate range of other types of visual culture. The most common entries in these albums are signatures, mottoes, and coats of arms, which link them to emblematic traditions. Music sheets are included on occasion, as well as poetry and text lifted from well-known literary sources. Alba feature pasted-in prints, often hand-coloured, as well as watercolour illustrations. The watercolours themselves are most certainly an untapped visual archive, influenced by various early modern visual traditions including costume books, natural histories, ethnographies, portraits, and prints.

16The watercolours made in London differ stylistically and technically from those produced elsewhere, suggesting that a geographically specific approach to alba amicorum may be fruitful.17 Many in the Van Meer album are intricate and competently executed. The watercolours made in London align closely with the limning tradition that flourished in the city during the period. The alba limnings were likely made in picture shops in the capital by artists who would have been familiar with the work of prominent court limners living nearby, such as Hilliard and Isaac Oliver.18 Situating the alba limnings within the broader tradition of limning in early modern London enables us to reassess these works in light of recent scholarship on portrait miniatures that has highlighted how their technique lent itself to a perceived sense of authenticity.19 Limning, understood as a “direct, unmediated representation of reality”, was an effective and persuasive means of conveying the veracity of what the artist had seen.20 The alba limnings feature numerous representations of James and the Jacobean court, which offer valuable insight into how the monarch’s public image was perceived, mediated, and circulated—especially by foreign observers engaging with the English court.

17Jacobean Limnings as a Genre

Technique

Limning is a technique of drawing in watercolour on vellum or paper. Alba limnings were painted using this technique; beyond this, they share various working methods and technical innovations that are usually considered specific to portrait miniatures. Their small format likewise recalls that of portrait miniatures.21 The watercolours themselves are often detailed, with particular attention paid to costume, settings, and jewellery; this is also a characteristic of portrait miniatures and costume books (see, for example, fig. 1). The ability to render watercolours on such a diminutive scale was the most important skill for limners painting portrait miniatures.

21

The emphasis on costume can be found in the depictions of James in Van Meer’s album. He is consistently shown in state dress; in some versions he wears ermine-trimmed red ceremonial robes and a crown, and holds a sceptre (fig. 2). The ermine has been depicted using tiny arrow shapes to give the illusion of fur, which continues down the edge of James’s robe. Elsewhere, James wears the full Order of the Garter robes (fig. 3). Here he is shown in a soft black hat with a feather, which is again rendered precisely, with thin strands of silver capturing the feather’s lightness.

Facial likenesses in alba limnings are rendered in an abbreviated form, painted with just a few strokes. Yet, while these illustrations lack the presumed attention to facial features found in portrait miniatures, they do not fail to capture individual likenesses. The limnings of James, for example, are immediately recognisable from his slightly sunken eyes and prominent facial hair (figs. 4 and 5). A similar approach was used by John White in his limnings of the New World. White’s figures are all shown with an “individualized” countenance, an evident preoccupation for the artist, yet close inspection reveals that he achieves this using broad strokes rather than minute detail (fig. 6).22 In many portrait miniatures of this period, particularly those by Nicholas Hilliard, an abbreviated or “economical” approach to facial features was clearly fundamental to the limner’s working practice (fig. 7).23 Hilliard was praised for his ability to do just this: John Harington commended the way in which he had produced a recognisable shorthand likeness of Queen Elizabeth I, in which “in white and blacke in foure lines only set downe the feature of the Queenes Majesties countenance, that it was even thereby to bee knowne”.24 Indeed, Norgate, writing on limning in the 1620s, emphasised how the first drawing of the face should be “exact and sure”, with “the lines being truely drawne”, associating authenticity with simplicity in facial features.25

22

This shorthand likeness of James can be seen as a skill in “quickness”, an important quality of portrait miniature painting. In contrast to oil, miniature paintings were completed in a relatively short time. According to Norgate, this process involved three sittings, the first “comonly takes up to two howres”, the second “three or fower howres or more”, and the last “two howres, or three, according to the patience of the sitter, or skill of the Lymner”.26 The implication here is that the more skilful the limner, the faster the process. Hilliard also emphasised the importance of speed, suggesting that the limner should “catch those louely graces wittye smilings, and those stolne glances wch sudainely like lighting passe and another Countenance taketh place”.27 Quickness and an economical approach to the rendering of features were considered to have rhetorical implications for the viewer, narrowing the temporal distance between a real person and those observing their likeness. Real gold and silver were used to embellish many of the alba limnings including, for example, that of Anna of Denmark, where gold and silver are liberally present in the jewellery (fig. 1). This aligns with the portrait miniaturist’s practice, for both Hilliard and Norgate advised the use of real gold and silver. Hilliard wrote that it “so enricheth and innobleth the worke that it seemeth to be the thinge it sefe [self]”.28 Norgate recounted a method of application of gold and silver that he had learnt from “Old Mr Hilliard”.29 In the years 1614–15, when Van Meer was in London compiling his album, gold and silver would have been in high demand by miniaturists. Hilliard’s Unknown Young Man against a Background of Flames (circa 1600) and Isaac Oliver’s A Man Consumed by Flames (fig. 8) both show sitters surrounded by fire that is brought to life with specks of gold. John White’s own application of gold to his limnings of the New World have been viewed as comparable to a contemporary portrait miniaturist’s approach.30 A striking example of White’s use of gold can be seen in A Timucuan Chief of Florida, where the jewelled components of the sitter’s costume have been rendered in real gold (fig. 9). Like the skills of quickness and abbreviation, the use of real gold and silver was thought to have added to the illusionistic veracity of the scene. Gold and silver are used to similar effect in the alba limnings, adorning costumes (particularly in the illustrations of Anna of Denmark) and even adding an illusionistic glimmer to the piles of coins found in a limning of James watching a cockfight (fig. 10).

26

It also appears that the hand responsible for the alba limnings adopted specific techniques used by miniaturists to render jewellery. The Van Meer limning of “Nobles damme d’Engleterre” shows a lady in a pink dress with a scooped neck, a ruff, and a high hat with a feather (fig. 11). The area around her face is damaged, but her necklaces are still discernible (fig. 12). Along with the fashionable black thread necklace found in the portraits of numerous female sitters of the period are the remains of silver. These black thread necklaces are commonly paired with a pearl choker, as seen, for example, in Isaac and Peter Oliver’s miniatures of female sitters from 1610–20, which show them in a distinct fashion probably influenced by the court masque (figs. 13 and 14). In these, the real silver used has tarnished to black. The use of silver to evoke the glimmer of a pearl was an innovation of Hilliard’s, who advised limners to “give the light of your Pearle with silver”. Hence the pearls in his and many later miniaturists’ work now have a dot of tarnished silver remaining.31 The string of silver around the lady’s neck in Van Meer’s album was most likely a shorthand to indicate pearls that had been picked up from portrait miniaturists.

31

Gentility

During the early seventeenth century, writers such as Hilliard sought to associate limning with gentility. The artist claimed that limning was “a kind of gentle painting” and that “none should meddle with limning but gentlemen alone”.32 Coombs associates this aspect of the portrait miniature with White’s watercolours, suggesting that this “gentle” nature was associated broadly with varying types of limning.33 Other types of limning, such as heraldry, were becoming increasingly popular among amateur gentlemen during the period, and portrait miniature painting has been described as the “perfect activity for the English ‘gentleman’ courtier and his wife”.34

32It was this gentlemanly class who also engaged with the album amicorum practice.35 While contributors to albums varied, the practice was particularly popular in learned humanist circles. In 1577, when asked to contribute to Abraham Ortelius’s album, Alexander Grapheus commented that it included the signatures of “so many learned men” and that by inserting his name he would be “cackling like a goose among swans”.36 Despite being of a learned and frequently a courtly class, contributors often provided their own illustrations to the albums, indicating that they saw this type of artistic endeavour as an appropriate gentlemanly activity. Indeed, in England, the early seventeenth century saw an increase in texts suggesting that both drawing and limning were appropriate skills for a gentleman and a part of the education of elite children.37 Not all felt that this was within their capabilities, however. Grapheus explained apologetically that he had been unable to procure an artist to add a “symbol” to his contribution for Ortelius: “I had thought of adding a symbol to my poem; but … there being no painter at hand whom I know … I abandoned my plan”.38 William Camden, in contrast, informed Ortelius that he had added a symbol himself but apologised for not having hired a professional painter to do so.39

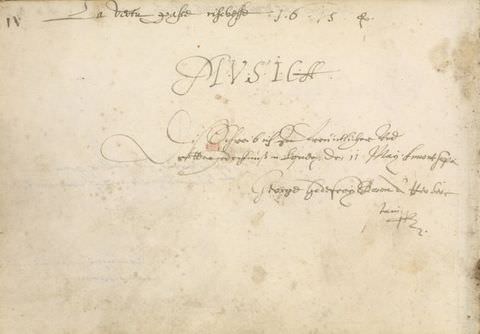

35Many of the signatures Van Meer collected in London came from the aristocratic and learned class and include, to name a few, James; Anna of Denmark; Prince Charles; Thomas Howard, earl of Suffolk, Ludovic Stewart, duke of Lennox; William Herbert, earl of Pembroke; and Philip Herbert, earl of Montgomery. It also contains many abbreviations of conventional expressions that would have been understood among this learned audience. For example, “M.V.S.I.C.A”, meaning “Mea ultima spes in Christo, Amen” (My highest hope is in Christ, amen), is found in Van Meer’s album and many other alba, indicating that alba were a form of communication exclusive to those with an educated background (fig. 15). Such abbreviations were more than pious formulas; they functioned as a kind of coded language legible only to the educated, and thereby reinforced a sense of belonging to an exclusive intellectual community. In this way, alba not only recorded connections but also actively constructed a community defined by shared knowledge and cultural capital. As Jason Harris has argued in his discussion of Ortelius’s album amicorum, these books represented an elite intellectual “circle of friends celebrating itself, of individuals glorying in the prestigious company they keep”.40

40

Hence, in alba creator and viewer overlapped. The audience for limnings was, more generally, also from a gentlemanly or royal circle. Roy Strong points out that “the regal origins of this art form [portrait miniature painting] are central to its understanding” and that “for the first fifty years or so miniatures remained almost exclusively a royal prerogative”.41 Similarly, White’s watercolours were probably destined for courtly circles, perhaps “originally intended to form a presentation album to be given to Queen Elizabeth I, Walter Raleigh or another patron at court”.42 Limning, as it was understood in England, would have been particularly well suited to the continental alba amicorum genre, which was likewise aimed at a learned, gentlemanly audience.

41Authenticity and Certa Testimonia

Both contemporary writers and modern-day scholars have emphasised that limnings, particularly portrait miniatures, were perceived to offer a kind of “unmediated access to reality”.43 Faraday has argued convincingly that it was not just the subject matter but also the very medium of limning—its working methods and materials—that led to contemporary audiences regarding the objects as possessing liveliness: something “living, alive-like or lifelike; forceful or potent; delightful or pleasing”.44 Beyond portrait miniatures, the quality of vivid authenticity was extended to other limnings, such as White’s illustrations, which were similarly presented as truthful records.45

43The claim to authenticity in alba was not just associated with imagery. The alba genre was fundamentally structured around the concept of testimonia—a term connoting both documentary evidence and rhetorical persuasion. As the German Lutheran reformer Philip Melanchthon noted, one of the principal purposes of alba was “ut certa habeant testimonia, quibuscum familiariter vixerint, et qui vera amicitia illis fuerint conjuncti” (that they may have certain testimonies/evidence, with whom they have lived familiarly, and who have been joined to them by true friendship).46 Alba thus functioned as a repository of certa testimonia, reliable evidence of personal relationships and intellectual kinship. In early-modern rhetorical theory, testimonia formed a part of inventio—the process of discovering arguments—and was understood as a form of proof.47 As Richard Serjeantson has argued, testimonia could also be used as a form of elocutio, or style, where its value lay less in first-hand experience and more in its ability to render an account vivid and persuasive, as if the audience had witnessed it themselves.48

46This dual rhetorical function is key to understanding the limnings in alba amicorum. By borrowing the medium and stylistic techniques of portrait miniatures—already embedded with notions of truthfulness—these images were able to persuade their viewers not only of the identities of those depicted but also of the veracity of the scenes, relationships, and experiences they recalled. The limning, then, operated as both a material and a rhetorical device, anchoring the album’s contents in visual testimony.

Other contemporary accounts demonstrate that the albums were perceived as truthful by their viewers. Contributors to Ortelius’s album, for example, viewed it not merely as a commemorative object but also as evidence of his character and affiliations. In 1582 Nicolaus Fabri Vilvordiensis wrote that the album “shows how much you favour the arts and those who cultivate them”, revealing how the album offered an insight not only into Ortelius’s circle but also into the very nature of his intellectual character. Grapheus similarly interpreted the album as a kind of testimony: “finding [your album amicorum] adorned with the symbols of so many learned men, I felt much gratified by your thinking me worthy of being recorded among your celebrated circle of friends”.49

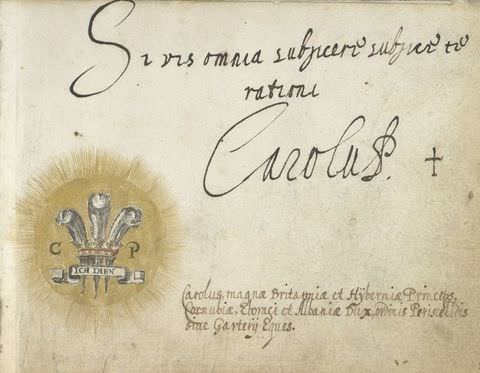

49Textual elements reinforced these albums’ claim to truth. The signatures—the most fundamental element of the album amicorum—acted as authenticating marks. Indeed, signatures were often accompanied by “manu propria” (with one’s own hand) or some variation, reiterating the authenticity of the entry.50 Mel Evans has shown that in Tudor England a signature served “as a means of authentication and authorisation for the contents of a written text”.51 In this light, the signatures of James, Anna of Denmark, and Prince Charles in Van Meer’s album are not just something Van Meer “collected” in isolation (figs. 16–18). As many of the images in the album represent James and the Jacobean court, these signatures can be seen as an authentication of the material. While we will never know if the individuals perused the rest of the album when they signed it, Ortelius’s accounts suggest that looking through an album was part of the performative act of a contributor.

50

The Royal Couple in Michael van Meer’s Album Amicorum

We have seen how both limning as a technique and alba as a genre were related to ideas of authenticity. Turning to Van Meer’s album amicorum and its illustrations of Jacobean London, we can now consider the implications of this on how royalty was depicted. Unlike various other types of limning—notably portrait miniatures—alba limnings were not commissioned by the king or queen. Despite this, they provide valuable information regarding the representation of the royal pair. In particular, given the association between alba and testimonia, with its role of convincing the audience of an eyewitness account, how James and the court were represented should be viewed as a reflection of how they wished to represent themselves to the urban milieu of London.

While monarchs would not have commissioned these limnings themselves, they must have been familiar with them, given their signatures in various alba. If they had been displeased with them, they had the authority to stop their circulation. More than this, James and Anna would have understood that their signatures and accompanying limnings would travel back to the continent. By the time Van Meer acquired their signatures, they were already accustomed to the practice of signing alba, for James’s signature appears in albums dating back to the late 1580s.52 They would also have recognised that such contributions were a means of both dissemination and communication. In the album of the Scotsman Sir Michael Balfour the signatures of James and Anna (fols. 31r and 32v) follow directly after that of Anna’s brother, Christian IV of Denmark (fol. 30v).53 All three are dated 1598, and the order of entries suggests that Christian’s signature was probably procured first. Album signing was therefore more than a perfunctory gesture: it functioned as a form of symbolic communication. Signatures and limnings projected identity and prestige, situated monarchs in international humanist networks, and interacted with those of other contributors, whose entries framed their own.54 The interactive dimension of this practice is underscored in Harris’s discussion of Ortelius’s album, which contributors even circulated among themselves, thereby reinforcing its role as a medium of exchange and communication.55

52The Royal Likeness

The royal likenesses found in alba limnings show a close affinity to the techniques of portrait miniature painting. Portrait miniaturists were known to create standardised likenesses of the monarch that were then reproduced by the artist to fill demand. For Elizabeth I, Hilliard developed the “mask of queenship” and subsequently the “mask of youth”.56 Similarly for James, Hilliard and his workshop devised three likeness types.57 There are similarities in these three miniature types; particularly recognisable features are James’s pale, slightly sunken eyes, his prominent facial hair, and the blue ribbon and Lesser George of the Order of the Garter, which are always around his neck. Likeness types of James also appear in various alba. The first type is best exemplified in Van Meer’s album (fig. 19). In this limning James’s head, shoulders, and costume are very similar to individual figures of James elsewhere (for example, fig. 20; see fig. 4). James, dressed in red ceremonial robes with an ermine lining, wears a crown and holds a sceptre (in some versions, an orb). Around his shoulders is the collar of the Order of the Garter. Another type, which shows James wearing the full Order of the Garter robes and a soft black hat with a feather, is also best exemplified in Van Meer’s album (see fig. 3).

56

If it were not for this image, where the king’s likeness is very similar to the first type, it might not have been obvious that a much more stylised illustration in an anonymous Folger album also depicts James (fig. 21).58 This illustration lacks the sense of movement of those in the Van Meer album, and the artist who created this stylised version was clearly not the one who painted the limnings of the king in the Van Meer album. The similarity of this illustration to others in the anonymous Folger album, which represent various figures from elsewhere in Europe, suggests that the compiler made the illustrations themselves, copying them from prototypes they had found on their travels. It indicates how limnings like these were adapted and disseminated.59

58

Anna also appears in various alba. In the album of Tobias Oelhafen von Schöllenbach, Anna wears a silver and pink dress (the skirt of which is worn over a drum-shaped wheel farthingale) with a low, scooped neckline and a high collar (fig. 22).60 Her blonde hair worn high, covered in jewels and adorned with a pink feather, she stands on a grassy mound—a feature also found in several other limnings in the Van Meer album—and holds a fan. The regularity with which this grassy mound appears in alba limnings suggests it was a repeated compositional tool used by a specific workshop. Anna’s hair, costume, and accessories are her distinguishing features, and her likeness is very close to her portrait painted by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger from the same date (fig. 23). The skirt, in particular, is a consistent feature of Anna’s dress in portraiture. The farthingale shape was a style Anna had worn for nearly two decades. Piero Contarini, the Venetian ambassador, remarked on this recognisable feature of Anna’s dress in 1617: “Her Majesty’s costume was pink and gold with so expansive a farthingale that I do not exaggerate when I saw it was four feet wide at the hips”.61 This style of dress was similar to Elizabeth I’s costume, and would have created a “sartorial consistency” in the early stages of Stuart rule in England.62 Significantly, it also tied Anna to her extended familial networks in Europe, where this style remained the height of fashion into the 1620s.63 Thus her representation balanced continuity with the English Elizabethan reign as well as retained her connections to the continent, an aspect of her self-representation that was evident throughout her life.64

60

Anna’s image in alba limnings was described by Schlueter as “conventional” and “indistinguishable from the generic English noblewoman that also appears in many travellers albums”.65 Indeed, there are similarities between the watercolour of Anna in the Oelhafen album and one captioned “Noble damoysselle van Engel” (Noble Lady from England) in Van Meer’s album (fig. 24). On the recto of the Van Meer sheet is another lady with a similar description, “Nobles damme d’Engleterre” (Noble Lady from England) (see fig. 11). These women are clearly two different people, but the artist responsible for both is likely the same: close details show similar brushstrokes, a sketchy, slightly untidy handling of the ruff, and the same application of gold and silver (figs. 25 and 26). Given the close relationship between the first illustration and that of Anna in the Oelhafen album, it is probable that the former depicts Anna of Denmark and that the hand that later inscribed the illustration with “Noble damoysselle van Engel” was mistaken.66 To later viewers of the album, Anna’s likeness was interpreted less as an individual image and more as typical of English noble fashions, which helps explain why her distinct features became confused with more generic watercolours of English noblewomen.

65

Having established a set of characteristics found frequently in alba limnings of James and Anna, we can identify the pair in further illustrations in Van Meer’s album and others. These include the view of London Bridge with a boat carrying a man in a red robe and an “elegantly dressed woman”;67 a horse-drawn carriage with a flap to open the side window to show a group of figures, with a man in a red robe and a woman with blonde hair and a low, scooped neckline facing us;68 and the pair holding what appears to be a Murano Venetian cup, alongside the figure of Van Meer (figs. 27–29).69 These renditions record supposed sightings of the royal pair in the public sphere, reflecting how they were possibly seen by foreigner observers rather than in the controlled context of their commissioned portraits; their value lies in showing Anna and James moving in public, rather than as static formal portraits. They point to a degree of public visibility and accessibility. Anna’s own engagement with the public was noted: the Spanish ambassador described how, during the 1604 coronation, she was “bending her body this way and that” to acknowledge the crowds, and that she “rose from her chair in the litter three times, with a laughing face and kissing the hands many times”.70

67

James’s likenesses in alba always show him wearing the collar of the Order of the Garter—or, in the case of him watching a cockfight, the blue ribbon and a gold mark representing the Lesser George—which accords with his representation in portrait miniatures. The prominence of the garter has been described by Elizabeth Goldring as a “potent signifier of his Englishness”.71 Indeed, this aspect of his dress is often emphasised. In the depictions of him standing alone (see fig. 4) and in a St. George’s Day procession, his leg is revealed to show the blue garter (fig. 30). The accession of the Scottish King James to the English throne led to a preoccupation with national identity for the monarch, especially following the failure to create the intended political union between Scotland and England. The emphasis of these English elements of the ceremonial attire would have served to assert his authority and claim to English identity. It is evident that James saw Hilliard’s limning practice as intimately connected to the visual representation of his predecessor Elizabeth I and thus as linking him to an English visual identity. Maintaining the patronage of Hilliard was a form of visual continuity that served to legitimise James’s reign and position him as the successor to the English queen. The images of King James in these alba amicorum, carried back to the continent by their owners, emphasised his new English national identity. At the same time, they projected his position as monarch of both England and Scotland, underscoring the idea of a united monarchy—even if the deeper political union he sought remained unrealised.

71

James is usually depicted in ceremonial robes, wearing the insignia or collar of the Order of the Garter, his crown, and other regalia more typical of official state portraiture. These attributes signify distance, hierarchy, and permanence—precisely the opposite of the intimate, ephemeral qualities associated with limning and its claim to quickness and authenticity. The juxtaposition of immediacy in technique with formality in subject matter creates a particular effect on the viewer, allowing them to feel both the proximity of an apparent eyewitness encounter and the distance of royal authority.

By contributing their signatures and mottoes to alba amicorum that also contained limnings of them, James and Anna were indirectly—though perhaps not intentionally—implicated in the dissemination of their images through continental Europe. Anna’s interest in limning has been noted, and her patronage of Isaac Oliver was regarded as part of a broader interest in using European artists to “secure a cosmopolitan mode of representation”.72 James has sometimes been characterised as indifferent to limning, and to portraiture more generally, an erroneous interpretation stemming from Sir Anthony Weldon’s highly critical account of the king.73 The alba limnings provide a more nuanced perspective. They show James actively engaging with European modes of visual communication and aware of his own likeness circulated in this form. This accords with his use of portrait miniatures: while Hilliard’s miniatures of the king have been described as “tedious”, James certainly used them as a means of circulating his likeness across Europe and beyond.74 Limnings made in England travelled as far as the Mughal court during this period; the ambassador Thomas Roe was recorded using a miniature by Isaac Oliver to represent the interests of James VI and I in negotiations with the emperor Jahangir in 1616. It has been argued that Roe used the object to represent not only himself but his country.75 Indeed, the technique of limning was understood contemporaneously to be an “English” one.76

72One of the persistent challenges in interpreting alba limnings lies in the ambiguity of authorship. While stylistic similarities suggest that many illustrations originated from a limited number of artists or workshops in London, others appear to have been copied or adapted by the album owners themselves. This multiplicity of sources complicates assumptions about the intended message or audience. If James or Anna were not directly involved in commissioning these images—as is almost certainly the case—the extent to which they can be said to promote royal authority becomes a question of reception rather than intent. Rather than functioning as monarch-controlled image dissemination, these limnings more likely reflected how courtly power was perceived, repurposed, and circulated by foreign visitors.

Processions and Visual Spectacle

Alba limnings also feature events such as processions, parliamentary sittings, and leisure activities. Large-scale events, particularly those involving temporary structures for royal occasions and processional entries into cities were, of course, published as prints for a wider audience.77 But the notion of capturing the fleeting moment of ephemeral smaller-scale events to convey immediacy was clearly more appropriate to the technique of limning.

77In Van Meer’s album, James is depicted travelling to Parliament with three attendants (see fig. 2); sitting in the House of Lords (fig. 31); participating in the St. George’s Day procession (see fig. 30); crossing the Thames (see fig. 27); and betting money on a cockfight (fig. 32). The descriptions (added in the latter part of the seventeenth century) that accompany these watercolours give specific details of the scenes. Underneath the processional limning, a caption reads “Op deese mannier gincks Coninks Jacobus in Engeland in processies met de ridderen van de Gartierre of Kauffebandt dat noch jaer leyex op St. Jores dach gehaen wordt” (In this manner goes King James of England in procession with the Knights of the Garter each year on St. George’s Day). Above the watercolour of James riding to Parliament with three attendants is the explanation that “Op deese manniere reyde de koninghen van Engelandt in het Parlemendt” (In this manner the king of England rides to Parliament), while the watercolour of James in the House of Lords is accompanied by the caption “Alsoo hout de koning in Englant raet in de vorgadering van het oppoer Parlem” (Thus the king of England holds counsel in the gathering of the upper Parliament).78

78

The term “manner” can be interpreted as referring to a customary practice, but the limnings seem to depict a specific event rather than a generalised activity. The so-called Addled Parliament, the second parliament of James VI and I’s reign, sat between 5 April and 7 June 1614. James travelled to the House of Lords for this parliament accompanied by Ludovic Stewart, second duke of Lennox, Gilbert Talbot, seventh earl of Shrewsbury, and William Stanley, sixth earl of Derby.79 There had not been a parliament since 1604, and another was not called until 1621, so presumably this limning, together with the one of James actually in the House of Lords, depicted very specific events that occurred during Van Meer’s stay in London. That is not to say that Van Meer himself witnessed these events but that the artists working in picture shops to create this type of limning were responding to current events and creating relevant and up-to-date illustrations.

79The limning of the St. George’s Day procession, in which James’s likeness belongs to the second type discussed here (for example, see fig. 4), shows an annual event that Van Meer may well have witnessed. The procession includes thirty figures and is split over two pages, allowing the artist to include a wider range of participants in the procession. This type of processional imagery is often found in a print format. As Lisa Pon explains, they were created in this fashion to “invite the reader/viewer to proceed sequentially, almost as a participant”.80 Indeed, James’s appearance twice in the procession adds to the interactive element of the composition, constructing a continuous narrative.81 Other limnings in the album also demanded viewer participation, most apparently in the example of the carriage with an opening flap door. This type of interaction allows the viewer to engage actively with the illustration, bringing an element of playfulness to the scene.82

80The depiction of James at a cockfight probably also commemorated a specific event (see fig. 32). We know that the king enjoyed this form of entertainment because, in 1617, James ordered that a cockfight take place in Lincoln, and it is recorded that the event “made his Majesty very merry”.83 Indeed, James was “so fond of cock-fighting that he indulged himself by watching it twice a week”.84 The cockpit in Van Meer’s album is likely the Whitehall Cockpit, which Inigo Jones renovated in 1629. It was octagonal and so, while Van Meer’s version is stylised, the eight columns point to the structure of the Whitehall one. Accounts of repairs to the Whitehall cockpit in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries show the extensive use of gold decoration for various cornices and other architectural features.85 These decorative features do not appear in Van Meer’s limning but, interestingly, the artist has made the columns appear almost to shimmer with gold, perhaps as a shorthand reference to the gold decorative elements in the Whitehall cockpit.

83The cockfight illustration reveals a new side to the representation of the monarch. While it is known and well recorded that James enjoyed hunting, and his Declaration of Sports (issued nationally in 1618) is a clear indication of his enthusiasm for sports, this is the only depiction of James participating in such an activity. The king appears informally seated in a chair, possibly with his outer cloak draped over it. His status is clear, however, as he is the only participant at the cockfight seated on a gold-embellished chair (in contrast to a crowded bench) and wearing a feather-adorned hat that contains a speck of gold, perhaps to indicate the Great Feather jewel James wore on a similar hat in a portrait attributed to John de Critz.86

86Cockfighting would certainly have had connotations of courtly prestige. As Heasim Sul points out, James’s Declaration of Sports banned cockfighting and bear-baiting, yet the “court was a great fan of blood sports”. This apparent paradox can be explained by the prestigious associations of blood sports with the “medieval elite whose privileges were based on their fighting arts”. Sul concludes that permitting the commoner to engage in such activities would be “an encroachment of their privilege”.87 This illustration therefore conveys a very specific message about royal and aristocratic privilege, while at the same time offering those who view the album a rare glimpse into elite pastimes normally closed to them. In this sense, the image both asserts exclusivity and simultaneously stages a controlled act of display, allowing outsiders to witness an elite sport without participating in it.

87Eiakintomino in St. James’s Park

Many more limnings in alba amicorum painted in London merit reassessment in light of the broader limning tradition. One worth considering here, which relates to James VI and I’s ambitions, shows a Native American surrounded by various animals in St. James’s Park (fig. 33). The caption above reads “Een jongheling uyt de virginus” (A young man from the Virginias), and below: “diese Indiaense voghelen en beasten, met den jongheling syn Ao: 1615: 1616 In St: James Parck op diertgaren byb Westmunster voor de Stadt London zsien geweest” (These Indian birds and beasts, with the young man, were seen in the year 1615–1616 in St. James’s Park at the Zoological Garden by Westminster in the city of London).88

88

The limning relates to White’s watercolours of the Algonquian peoples, especially in its attention to the costume to denote nationality and ethnicity. The pearl necklace, heightened with silver, worn by the figure draws on limning techniques originating with Hilliard, further placing this illustration in the tradition of limning and of the techniques used to depict the jewellery of Jacobean court sitters.

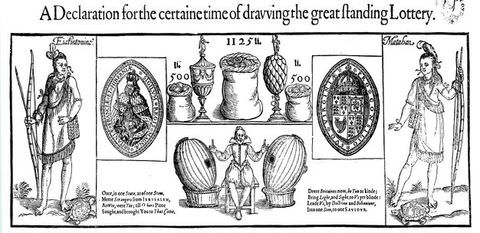

The figure has been identified as Eiakintomino from a surviving Virginia Company lottery broadside, which depicts a comparable individual and another Native American (identified as Matahan), alongside a small portrait of James (fig. 34). The composition, particularly the use of a grassy mound on which the figure stands, closely resembles the aforementioned limnings of James and Anna in the album, suggesting that it originated from the same picture shop or artist’s workshop.89

89

Schlueter discusses this watercolour in a chapter titled “Other Curiosities”, categorised as such because “of their unusualness of subject (to twenty-first century eyes) or the elusiveness of meaning”.90 The depiction of Eiakintomino, however, is neither unusual nor elusive, and should be understood as an expression of colonial authority. The illustration seems typical when it is seen in the context of White’s limnings of the New World and contemporary costume books containing limnings of people of different ethnicities. What distinguishes it is its being part of an album that contained illustrations depicting James, Anna, and the Jacobean court. Indeed, visually it appears to have been executed in the same workshop. The caption states that Eiakintomino and the unusual animals could be seen in St. James’s Park, an area of land James converted from a swamp to a garden for exotic animals at the time of his accession.91 This situates Eiakintomino in a royal and imperial framework. Some of the animals in the park were supplied by the Virginia Company, underscoring the deep connections between the figure’s presence in St. James’s Park and the Crown’s colonial enterprise.

90The placement of Eiakintomino on royal land, where he is exhibited alongside foreign animals and plants, was a powerful public spectacle. Such spectacles converted living bodies into “living theater” and “moving memorabilia”, as Peter C. Mancall observes of a 1550 performance by Brazilian Indigenous peoples for Henri II in Rouen.92 That Eiakintomino was a similarly performative symbol of imperial dominance and Christianising mission is reinforced by the Virginia Company broadside. It includes two short inscriptions portraying the Powhatan men as seekers of Christian enlightenment, pleading for guidance from the English. This constructed narrative of willing conversion bolstered the ideological framework of colonisation.

92Van Meer’s decision to include a limning of Eiakintomino—a medium deeply associated with fidelity and truth—lent the image additional authority. The medium suggested that this was not an allegory or fantasy but a documented reality that Van Meer had witnessed. The caption’s claim that the image was of an actual scene in St. James’s Park further reinforced its perceived authenticity.

This authenticity would have carried particular weight in the limning’s circulation beyond England. Taken back to continental Europe by their owners, limnings like these would have served as a visual testament to the colonial reach and civilising mission of James’s reign, communicating ideas of conquest, control, and conversion to a European audience. Through limning the colonial ambitions of Jacobean England were not only documented but also dignified and made exportable. This image emerges not as an oddity but as a strategic visual articulation of empire that was visible to the monarchs who signed the album and that circulated through elite networks.

Conclusion

Innumerable limnings of the Jacobean court and London can be found in the alba amicorum of travellers to the city during the first quarter of the seventeenth century. This article has situated these illustrations in the broader limning tradition that flourished in early modern London, and expanded the definition of limning beyond portrait miniatures to include a wider range of visual sources. In doing so, it has shown how characteristics typically associated with English limning, including quickness, authenticity, and immediacy, were deployed in these albums.

These limnings were not commissioned by the monarchs themselves but were produced and circulated independently, often by or for foreign travellers who engaged with the English court. Even without direct royal control, these limnings reflect important aspects of how James, Anna, and the Jacobean court were perceived in public and abroad. Their presence in the albums, alongside their royal signatures, suggests a complex and semi-public form of image-making that was not tightly controlled by the Crown but nonetheless reinforced certain visual codes of legitimacy, access, and authority.

In this context, the album amicorum and the limnings form a mutually reinforcing structure: the album insists on its authority through the logic of certa testimonia (documentary proof of contact and connection), while the limning’s quickness and vividness lend it visual immediacy and persuasive power. From the abbreviated likenesses of James that collapse the temporal gap between sitter and image to the representations of public events and ephemeral courtly spectacle, the limnings blur the line between documentation and performance.

The representations in these works of James and Anna, whether in procession, at sporting events, or in ceremonial dress, were thus not official portraits, but nor were they entirely informal. Instead, they reveal one way in which visual representations of royalty were mediated through international networks and constructed from within London’s vibrant image economy. Seen in this light, the alba limnings become crucial sources for understanding how royal identity and Jacobean culture were interpreted, circulated, and received across European social and intellectual circles.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Catriona Murray for our constructive conversations on this topic in its preliminary stages. This research benefited from discussions at the workshop organised in conjunction with this issue, and I would also like to thank the editors of this issue and the journal for organising the workshop. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions in the preparation of this article.

About the author

-

Sophie Ninetta Rhodes completed a collaborative doctoral award between the University of Cambridge and the National Portrait Gallery in 2023. Her doctoral research focused on Peter Oliver and the miniature in Stuart England, and she has published research on cabinet miniature copies in the collection of Charles I. She has held a pre-doctoral fellowship at the Yale Center for British Art and a curatorial placement at the National Portrait Gallery, both funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Footnotes

-

1

Nicholas Hilliard, A Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning by Nicholas Hilliard, Together with a More Compendious Discourse concerning ye Art of Liming by Edward Norgate with a Parallel Modernized Text, ed. R. K. R. Thornton and T. G. S. Cain (Ashington: Mid-Northumberland Arts Group with Carcanet New Press, 1981). Norgate’s Miniatura exists in two versions: the first, compiled around 1627–28, and a revised version dated 1648, which is similar to the first, but with some important developments in artistic taste and miniature practice recorded. Quotations from Norgate are taken from the second version. Both texts existed only in manuscript form and were intended to be circulated to artists, intellectual virtuosos, and gentlemen. Edward Norgate, Miniatura, or, The Art of Limning, ed. Jeffrey M. Muller and Jim Murrell (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 12–20. ↩︎

-

2

Muller and Murrell, Edward Norgate, 58. ↩︎

-

3

Henry Peacham, The Compleat Gentleman (London: London: John Legat for Francis Constable, 1622), 105. ↩︎

-

4

See, in particular, the following articles from European Visions: American Voices, ed. Kim Sloan (British Museum Press, 2009): Katherine Coombs, “‘A Kind of Gentle Painting’: Limning in 16th-Century England”, 77–84; Timea Tallian, “John White’s Materials and Techniques”, 72–76; and Stephanie Pratt, “Truth and Artifice in the Visualization of Native Peoples: From the Time of John White to the Beginning of the 18th Century”, 33–40. More recently, Christina Faraday and Anne-Valérie Dulac have discussed the relationship between White’s watercolours and certain characteristics of portrait miniature painting. Christina J. Faraday, “Lively Limning: Presence in Portrait Miniatures and John White’s Images of the New World”, British Art Studies, 17 (2020), DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-17/cfaraday; Anne-Valérie Dulac, “Fish in Watercolour: John White’s Lively Specimens”, RursuSpicae: Transmission, Réception et Réécriture de Textes, de l’Antiquité au Moyen Âge 4 (2022), DOI:10.4000/rursuspicae.2198. ↩︎

-

5

Coombs, “‘A Kind of Gentle Painting’”, 81–82. ↩︎

-

6

For example, a Miles Coverdale Bible at the British Library (C.45.a.13) contains a limning of James VI and I that is related to versions found in the alba amicorum discussed in this article, for example in fol. 385v of Michael van Meer’s album amicorum, 1614–15, La.III.283, University of Edinburgh Library Heritage Collections. ↩︎

-

7

An important starting point for studying alba amicorum, which also discusses the roots of the practice of creating the albums, is Max Rosenheim, “The Album Amicorum”, Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity 62, no. 1 (1910): 251–308. ↩︎

-

8

For more on the origins of alba amicorum, see Sophie Reinders and Jeroen Vandommele, “Introduction: A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, in “A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, ed. Sophie Reinders and Jeroen Vandommele, special issue, Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022): 3–4, DOI:10.51750/emlc12166. ↩︎

-

9

See, for example, the album owned by Christoph von Teuffenbach, which contains signatures on manuscript sheets interwoven into a copy of Philip Melanchthon’s Loci communes. Christoph von Teuffenbach’s album amicorum, 1548–68, Reformationsgeschichtliche Forschungbibliothek, Wittenberg, SS 3546. ↩︎

-

10

Several articles deal with how alba amicorum were used as a means of self-fashioning by their owners, who employed their collection of prestigious signatures to demonstrate something about themselves. For example, June Schlueter has suggested that the album amicorum of Aernout van Buchell was a means “to construct, to authorize, and to advertise ‘the self’”. June Schlueter, “‘His Best Part Lies Hidden in His Learned Heart’: Aernout van Buchell’s Alba Amicorum”, in “A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, ed. Reinders and Vandommele, Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022): 38, DOI:10.51750/emlc12170. ↩︎

-

11

See Reinders and Vandommele’s “Introduction” to their special issue on alba amicorum for important current historiography on the topic. June Schlueter and Thomas Brochard are the only scholars to have discussed alba amicorum in a British context recently. June Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time (London: British Library, 2011); Thomas Brochard, “Scots and the Netherlands as Seen through Alba Amicorum, 1540s–1720s”, Dutch Crossing 46, no. 1 (2022): 3–26; Thomas Brochard, “Scots and France as Seen through Alba Amicorum, 1540s–1720s”, Revue d’Études Anglophones 19, no. 2 (2022), DOI:10.4000/erea.13289; Thomas Brochard, “Scottish Northerners in Alba Amicorum, c. 1540–c. 1720”, Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 43, no. 2 (2023): 87–111. ↩︎

-

12

Michael van Meer’s album amicorum, 1614–15. For biographical information on Van Meer, see June Schlueter, “Michael van Meer’s Album Amicorum, with Illustrations of London, 1614–15”, Huntington Library Quarterly 69, no. 2 (2006): 301–14. ↩︎

-

13

Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 29. ↩︎

-

14

Margaret F. Rosenthal, “Fashions of Friendship in an Early Modern Illustrated Album Amicorum: British Library, MS Egerton 1191”, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 39, no. 3 (2009): 620. ↩︎

-

15

The locations of these alba amicorum are as follows: Jacob Fetzer, 1610–20 (Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, 231 Blankenburg 8^o^); Frederic de Botnia, 1616–18 (British Library, London, Add MS 16889); Tobias Oelhafen von Schöllenbach, 1623–25 (British Library, Egerton MS 1269); Georg Holzschuher von Neuenbürg (British Library, Egerton MS 1264); Giese [Raban], seventeenth century (Forum Auctions sale, 21 November 2019, Lot 360). ↩︎

-

16

Reinders and Vandommele, “Introduction”, 2–3. Marika Keblusek also addresses this in her contribution to their special issue. Marika Keblusek, “A Paper World: The Album Amicorum as a Collection Space”, in “A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, ed. Reinders and Vandommele, Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022): 14–35, DOI:10.51750/emlc12169. ↩︎

-

17

The idea that text or imagery in alba relates to a specific culture has been argued in relation to the Dutch sonnets by Ad Leerintveld and Jeroen Vandommele, “Instruments of Community: Dutch Sonnets in Alba Amicorum, 1560–1660”, in “A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, ed. Reinders and Vandommele, Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022): 72, DOI:10.51750/emlc12172. They suggest that this was an intentional way of positioning the language as on a par with Latin, thus demonstrating how a language (or, in this case, an art associated with one place) could be disseminated to assert its status. ↩︎

-

18

In her study of the album amicorum of Sigismund Ortel, which includes numerous watercolours of costume and daily life in Italy, Rosenthal suggests that owners of the albums may have “collected the images in public markets or fixed shops, or perhaps from local cartolai [stationers]”. Rosenthal, “Fashions of Friendship in an Early Modern Illustrated Album Amicorum”, 620. A similar practice probably went on in London, where Jane Schlueter has similarly suggested that “picture-shops” were responsible for creating the limnings produced there. Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 23. ↩︎

-

19

See particularly Christina Faraday, “‘It Seemeth to Be the Thing Itsefe’: Directness and Intimacy in Nicholas Hilliard’s Portrait Miniatures”, Études Épistémè: Revue de Littérature et de Civilisation (XVIe–XVIIIe Siècles) 36 (2019), DOI:10.4000/episteme.5292. ↩︎

-

20

Faraday, “‘It Seemeth to Be the Thing Itsefe’”. ↩︎

-

21

The album of the German scholar Giese Raban, for example, which contains numerous signatures and illustrations compiled in London in about 1620, measures only 86 × 110 mm. ↩︎

-

22

Pratt, “Truth and Artifice in the Visualization of Native Peoples”, 34. ↩︎

-

23

This idea is discussed most recently by Faraday, “‘It Seemeth to Be the Thing Itsefe’”, 36. ↩︎

-

24

Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso in English Heroicall Verse, trans. Sir John Harington (London: Richard Field, 1591), 278. ↩︎

-

25

Muller and Murrell, Edward Norgate, 71. ↩︎

-

26

This is according to Norgate’s second version of his treatise. His early version suggests a longer period of time for the second sitting, of around four or five hours, which was amended in copied versions of this early treatise to around five or six hours. Norgate’s attempts to suggest, in his second treatise, that it probably took less time to create a miniature than it actually did highlights the value placed in the limner’s ability to capture a likeness quickly. Muller and Murrell, Edward Norgate, 72–73, 144. ↩︎

-

27

R. K. R. Thornton and T. G. S. Cain, eds., A Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning by Nicholas Hilliard, Together with a More Compendious Discourse concerning ye Art of Liming by Edward Norgate with a Parallel Modernized Text (Ashington: Mid-Northumberland Arts Group with Carcanet New Press, 1981), 76–77. This argument is put forward by Faraday, who associates this passage with the limner’s need to work quickly on the sitter’s facial features. Faraday, “‘It Seemeth to Be the Thing Itsefe’”. ↩︎

-

28

Thornton and Cain, A Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning, 62–64. ↩︎

-

29

Muller and Murrell, Edward Norgate, 80. ↩︎

-

30

Faraday, “Lively Limning”. ↩︎

-

31

Thornton and Cain, A Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning, 98. ↩︎

-

32

Thornton and Cain, A Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning, 43. ↩︎

-

33

Coombs, “‘A Kind of Gentle Painting’”, 77. ↩︎

-

34

Kim Sloan, A Noble Art: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters, c.1600–1800 (London: British Museum Press, 2000), 40–41. ↩︎

-

35

Sir Balthazar Gerbier, a gentleman miniaturist who produced several portrait miniatures, even signed an album amicorum. See Cornelis de Montigny de Glarges’s album amicorum, diplomat, National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague, 75 J 48. ↩︎

-

36

Abraham Ortelius, Abrahami Ortelii (geographi Antverpiensis) et virorum eruditorum ad eundem et ad Jacobum Colium Ortelianum (Abrahami Ortelii sororis filium), ed. Jan Hendrik Hessels (London: Typis Academiae, 1887), 163. Abraham Ortelius’s album amicorum is at Pembroke College, University of Cambridge, MS LC.2.113. ↩︎

-

37

Various texts mention the suitability of limning for gentlemen. An early example is Sir Thomas Elyot’s The Boke Named the Governour (1546). These ideas can be found in much of Peacham’s writings, including The Compleat Gentleman. ↩︎

-

38

Ortelius, Abrahami Ortelii, 164. ↩︎

-

39

Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 22. ↩︎

-

40

Jason Harris, “The Practice of Community: Humanist Friendship during the Dutch Revolt”, Texas Studies in Literature and Language 47, no. 4 (2005): 318. ↩︎

-

41

Roy Strong, Artists of the Tudor Court: The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered 1520–1620 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983), 11. ↩︎

-

42

Jenny Bescoby et al., “New Visions of a New World: The Conservation and Analysis of the John White Watercolours”, British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 1 (2007): 47. ↩︎

-

43

Christina Faraday, Tudor Liveliness: Vivid Art in Post-Reformation England (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2023), 78. ↩︎

-

44

Faraday, Tudor Liveliness, 9. ↩︎

-

45

Faraday, “Lively Limning”. Anne-Valérie Dulac argues that White’s watercolours of fish are “brought to life” through the medium of watercolour, and expands on the lively nature of these limnings. Dulac, “Fish in Watercolour”. See also Dulac, “The Colour of Lustre: Limning by the Life”, Revue Électronique d’Études sur le Monde Anglophone 12, no. 2 (2015), DOI:https://doi.org/10.4000/erea.4402. ↩︎

-

46

Judicium Philippi Melanchthonis de albis amicorum, cited in Robert Keil and Richard Keil, Die deutschen Stammbücher des sechzehnten bis neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (Berlin: E. Erote’sche, 1893), 9. ↩︎

-

47

Faraday, Tudor Liveliness, 100. ↩︎

-

48

R. W. Serjeantson, “Testimony: The Artless Proof”, in Renaissance Figures of Speech, ed. Gavin Alexander, Katrin Ettenhuber, and Sylvia Adamson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 182–83. ↩︎

-

49

Abrahami Ortelii (geographi Antverpiensis) et virorum eruditorum ad eundem et ad Jacobum Colium Ortelianum (Abrahami Ortelii sororis filium), ed. Jan Hendrik Hessels (London: Typis Academiae, 1887), 280, 163, quoted in Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 27. ↩︎

-

50

As noted by Schlueter, “Michael van Meer’s Album Amicorum”, 304. ↩︎

-

51

Mel Evans, Royal Voices: Language and Power in Tudor England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 57. ↩︎

-

52

See Hans Schreitter’s album amicorum, 1589, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart, 888–89, fol. 4. ↩︎

-

53

Album amicorum of Sir Michael Balfour, later Lord Balfour of Burleigh, 1596–1610, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, MS.16000. ↩︎

-

54

Reinders and Vandommele, “Introduction”, 10. The articles in their special issue discuss the international networks of album owners. Reinders and Vandommele, eds., “A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022). ↩︎

-

55

Harris, “The Practice of Community”, 299. ↩︎

-

56

For Hilliard’s development of these likenesses, see Elizabeth Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), 172–76, 212–16. ↩︎

-

57

Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard, 254. ↩︎

-

58

[Royal, military, and court costumes of the time of James I], “probably intended for or extracted from an album amicorum”, Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, ART Vol. c91. ↩︎

-

59

An unusual further use of this illustration type can be found in a Miles Coverdale Bible at the British Library (C.45.a.13). This illustration has not been published. Interestingly, it is accompanied by a view of Windsor Castle. The Van Meer album also contains a view of Windsor Castle (La.III.283, fol. 179r). Given this, it is possible that these limnings were made at a similar date and possibly copied from the type of illustration made for alba. ↩︎

-

60

Tobias Oelhafen von Schöllenbach’s album amicorum, 1623–25, British Library, Egerton MS 1269. ↩︎

-

61

Allen Hinds, Calendar of Papers and Manuscripts Relating, to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy, vol. 15, 1617–1619 (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1909), 80, no. 135. ↩︎

-

62

Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021), 129. ↩︎

-

63

Field, Anna of Denmark, 129. ↩︎

-

64

For more on the importance of Anna’s identity as connected to her family in northern Europe, see Field, Anna of Denmark, ch. 1. ↩︎

-

65

Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 82. ↩︎

-

66

Indeed, Schlueter points out that this later hand made a mistake with the identity of the lord mayor’s wife. Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 66. ↩︎

-

67

Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 46. Schlueter describes the passengers in the boat as “important cargo” but does not suggest they are James and Anna. ↩︎

-

68

Related to this is another sheet from Van Meer’s album (La.III.283, fol. 158v). A version with a flap can also be found in the anonymous Folger album (ART Vol. c91, no. 7a). ↩︎

-

69

Schlueter has identified this couple as Adam Gall von Krackwitz (who has added his entry to Van Meer’s album on this page) and his wife. Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 35–36. It is possible, however, that this couple represents Anna and James. Anna, in particular, has similar hair with a feather, jewels, and dress to how she appears in figures 22 and 24. The couple appear to be holding a Venetian glass cup, and Van Meer stands apart from them. ↩︎

-

70

Janette Dillon, The Language of Space in Court Performance, 1400–1625 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 35; Mark Hutchings and Berta Cano-Echevarría, “The Spanish Ambassador’s Account of James I’s Entry into London, 1604 [with Text]”, Seventeenth Century 33, no. 3 (2018): 267. ↩︎

-

71

Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard, 254. ↩︎

-

72

Field, Anna of Denmark, 12. ↩︎

-

73

Goldring provides a more nuanced assessment of James’s interest in portrait miniatures in Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard, 251. There remains, however, an enduring view of James as a monarch uninterested in the visual arts, stemming from Anthony Weldon’s The Court and Character of King James I: Written and Taken by Sir A: W Being an Eye, and Eare Witnesse (London: R.I., 1650). ↩︎

-

74

Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1998), 52. ↩︎

-

75

Anne-Valérie Dulac, “Miniatures between East and West: The Art(s) of Diplomacy in Thomas Roe’s Embassy”, Études Épistémè: Revue de Littérature et de Civilisation (XVIe–XVIIIe Siècles) 26 (2014), DOI:10.4000/episteme.343. ↩︎

-

76

Norgate claims the limners of “our Nation” are far superior to others in his treatise. Muller and Murrell, Edward Norgate, 58. The ideas that limning was an “English idiom” is further examined in Sophie Rhodes, “Translated into English Lymning: The Cabinet Miniature Copies of Peter Oliver (c1589–1647)”, British Art Journal 24, no. 2 (2023): 9–10. ↩︎

-

77

For example, the elaborate engravings by William Kip for The Arches of Triumph, erected for James VI and I’s arrival in London in 1603, published by Stephen Harrison in 1604 (British Museum, 1880,1113.5776). ↩︎

-

78

The translations here are taken from Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 79–80. ↩︎

-

79

Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 79. ↩︎

-

80

Lisa Pon, A Printed Icon in Early Modern Italy: Forlì’s Madonna of the Fire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 168. ↩︎

-

81

For the use of the same figure twice to present a continuous narrative, see Lew Andrews, Story and Space in Renaissance Art: The Rebirth of Continuous Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998). ↩︎

-

82

Faraday has demonstrated the connection between liveliness and lift-the-flap educational prints in Faraday, Tudor Liveliness, 110–11. Elsewhere, Suzanne Karr Schmidt has described how interactive prints “came alive” in the hands of the viewer. Suzanne Karr Schmidt, Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 14. ↩︎

-

83

George Greaves, Manuscripts of Lincoln Corporation Records, vol. 1 (London: Lincoln Record Society, 1912), 94, https://archive.org/details/manuscriptsoflin00greauoft/page/n5/mode/2up, quoted in Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 50. ↩︎

-

84

Heasim Sul, “The King’s Book of Sports: The Nature of Leisure in Early Modern England”, International Journal of the History of Sport 17, no. 4 (2000): 173. ↩︎

-

85

Payments were made to Matthew Goodricke. John H. Astington, “The Whitehall Cockpit: The Building and the Theater”, English Literary Renaissance 12, no. 3 (1982): 306–7. ↩︎

-

86

Attributed to John de Critz, James VI and I, circa 1606, Dulwich Picture Gallery DPG548. His costume and hat are also very similar. ↩︎

-

87

Sul, “The King’s Book of Sports”, 173. ↩︎

-

88

Schlueter notes that this later comment below the watercolour had been mistakenly written as “1615–1616” rather than “1614–1615”, which would make more sense as Van Meer was in London in 1614–15. Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 135. ↩︎

-

89

Lionel Cust discusses the Jacobean picture shop, referencing how Robert Peake had a picture shop that provided both painted and engraved images. Lionel Cust, “The Fine Arts: I. Painting, Sculpture, and Engraving”, in Shakespeare’s England: An Account of the Life and Manners of His Age, vol. 2 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916), 13. ↩︎

-

90

Schlueter, The Album Amicorum & the London of Shakespeare’s Time, 126. ↩︎

-

91

See Caroline Grigson, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England (Oxford University Press, 2016), 38. ↩︎

-

92

Peter C. Mancall, “‘Collecting Americans’: The Anglo-American Experience from Cabot to NAGPRA”, in Collecting across Cultures: Material Exchanges in the Early Modern Atlantic World, ed. Daniela Bleichmar and Peter C. Mancall (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 195. ↩︎

Bibliography

Alba Amicorum

Sir Michael Balfour, later Lord Balfour of Burleigh. 1596–1610. MS.16000. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Frederic de Botnia. 1616–18. Add MS 16889. British Library, London.

Cornelis de Montigny de Glarges, diplomat. 75 J 48. KB National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague.

Jacob Fetzer. 1610–20. 231 Blankenburg 8^o^. Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

Georg Holzschuher von Neuenbürg. Egerton MS 1264. British Library, London.

Tobias Oelhafen von Schöllenbach. 1623–25. Egerton MS 1269. British Library, London.

Abraham Ortelius. MS LC.2.113. Pembroke College, University of Cambridge.

Giese (Raban), ?scholar and medical doctor, seventeenth century. Forum Auctions sale, 21 November 2019, Lot 360.

[Royal, military, and court costumes of the time of James I], “probably intended for or extracted from an album amicorum”. Early seventeenth century. ART Vol. c91. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC.

Hans Schreitter. 1583–1614. Cod. Hist. 2^o^ 888–89. Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart.

Christoph von Teuffenbach. 1548–68. SS 3546. Reformationsgeschichtliche Forschungbibliothek, Wittenberg.

Michael van Meer. 1613–35. La.III.283. University of Edinburgh Library Heritage Collections.

Printed Sources

Andrews, Lew. Story and Space in Renaissance Art: The Rebirth of Continuous Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Ariosto, Ludovico. Orlando Furioso in English Heroicall Verse. Translated by Sir John Harington. London: Richard Field, 1591.

Astington, John H. “The Whitehall Cockpit: The Building and the Theater”. English Literary Renaissance 12, no. 3 (1982): 301–18.

Bescoby, Jenny, Judith Rayner, Janet Ambers, and Duncan Hook. “New Visions of a New World: The Conservation and Analysis of the John White Watercolours”. British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 1 (2007): 9–22.

Brochard, Thomas. “Scots and France as Seen through Alba Amicorum, 1540s–1720s”. Revue d’Études Anglophones 19, no. 2 (2022). DOI:10.4000/erea.13289.

Brochard, Thomas. “Scots and the Netherlands as Seen through Alba Amicorum, 1540s–1720s”. Dutch Crossing 46, no. 1 (2022): 3–26.

Brochard, Thomas. “Scottish Northerners in Alba Amicorum, c. 1540–c. 1720”. Journal of Scottish Historical Studies 43, no. 2 (2023): 87–111.

Coombs, Katherine. “‘A Kind of Gentle Painting’: Limning in 16th-Century England”. In European Visions: American Voices, edited by Kim Sloan, 77–84. London: British Museum Press, 2009.

Coombs, Katherine. The Portrait Miniature in England. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1998.

Cust, Lionel. “The Fine Arts: I. Painting, Sculpture, and Engraving”. In Shakespeare’s England: An Account of the Life and Manners of His Age. Vol. 2, 1–14. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916.

Dillon, Janette. The Language of Space in Court Performance, 1400–1625. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Dulac, Anne-Valérie. “The Colour of Lustre: Limning by the Life”. Revue Électronique d’Études sur le Monde Anglophone 12, no. 2 (2015). DOI:https://doi.org/10.4000/erea.4402.

Dulac, Anne-Valérie. “Fish in Watercolour: John White’s Lively Specimens”. RursuSpicae: Transmission, Réception et Réécriture de Textes, de l’Antiquité au Moyen Âge 4 (2022). DOI:10.4000/rursuspicae.2198.

Dulac, Anne-Valérie. “Miniatures between East and West: The Art(s) of Diplomacy in Thomas Roe’s Embassy”. Études Épistémè: Revue de Littérature et de Civilisation (XVIe–XVIIIe Siècles) 26 (2014). DOI:10.4000/episteme.343.

Evans, Mel. Royal Voices: Language and Power in Tudor England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Faraday, Christina. “‘It Seemeth to Be the Thing Itsefe’: Directness and Intimacy in Nicholas Hilliard’s Portrait Miniatures”. Études Épistémè: Revue de Littérature et de Civilisation (XVIe–XVIIIe Siècles) 36 (2019). DOI:10.4000/episteme.5292.

Faraday, Christina J. “Lively Limning: Presence in Portrait Miniatures and John White’s Images of the New World”. British Art Studies 17 (2020). DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-17/cfaraday.

Faraday, Christina J. Tudor Liveliness: Vivid Art in Post-Reformation England. London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2023.

Field, Jemma. Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021.

Goldring, Elizabeth. Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019.

Greaves, George. Manuscripts of Lincoln Corporation Records. Vol. 1. London: Lincoln Record Society, 1912. https://archive.org/details/manuscriptsoflin00greauoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

Grigson, Caroline. Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Harris, Jason. “The Practice of Community: Humanist Friendship during the Dutch Revolt”. Texas Studies in Literature and Language 47, no. 4 (2005): 299–325.

Hilliard, Nicholas, and Edward Norgate. A Treatise concerning the Arte of Limning by Nicholas Hilliard, Together with a More Compendious Discourse concerning ye Art of Liming by Edward Norgate with a Parallel Modernized Text. Edited by R. K. R. Thornton and T. G. S. Cain. Ashington: Mid-Northumberland Arts Group with Carcanet New Press, 1981.

Hinds, Alan. Calendar of Papers and Manuscripts Relating, to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy. Vol. 15, 1617–1619. London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1909.

Hutchings, Mark, and Berta Cano-Echevarría. “The Spanish Ambassador’s Account of James I’s Entry into London, 1604 [with Text]”. Seventeenth Century 33, no. 3 (2018): 255–77.

Keblusek, Marika. “A Paper World: The Album Amicorum as a Collection Space”. Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022): 14–35. DOI:https://doi.org/10.51750/emlc12169.

Keil, Robert, and Richard Keil, Die deutschen Stammbücher des sechzehnten bis neunzehnten Jahrhunderts. Berlin: E. Erote’sche, 1893.

Leerintveld, Ad, and Jeroen Vandommele. “Instruments of Community: Dutch Sonnets in Alba Amicorum, 1560–1660”. In “A Renaissance for Alba Amicorum Research”, edited by Sophie Reinders and Jeroen Vandommele, special issue, Early Modern Low Countries 6, no. 1 (2022): 71–102. DOI:https://doi.org/10.51750/emlc12172.