Distant Relations

Distant Relations: The Palatine Family, Propaganda, and Print in Early Stuart Britain

By Catriona Murray

Abstract

The marriage of Elizabeth Stuart to Frederick V, Elector Palatine, in February 1613, offered a lavish counter-attraction to the solemn mourning that had accompanied the death of her brother, Henry, Prince of Wales, just a few months before. Amid dynastic rupture, the match fortuitously shifted the focus from its recent loss onto the future of the line. Indeed, following the birth of Prince Frederick Henry in 1614, and for the next sixteen years until the birth of a healthy son to King Charles I and his consort, Queen Henrietta Maria, the ever-growing Palatine brood represented the next stage in the Stuart succession. Separated by distance from their potential subjects, it was important that the electoral couple continued to cultivate ties with the British people and, as their family grew, a familiarity with the prospective royal line was encouraged. A steady stream of printed images was enlisted in this campaign, designed to introduce the public back home to the Palatine family. Tracing the development of their visual portrayal in line with the shifting fortunes of the royal couple and their children, this article explores how these representations sought to naturalise a foreign royal family while forging cross-European dynastic loyalties. Images of Elizabeth’s family, whether portrayed as a lineal standby or even as an alternative, could endorse, or indeed complicate, dynastic rhetorics. As I shall argue, the affective bonds encouraged in word and image actually risked splitting Stuart allegiances.

Introduction

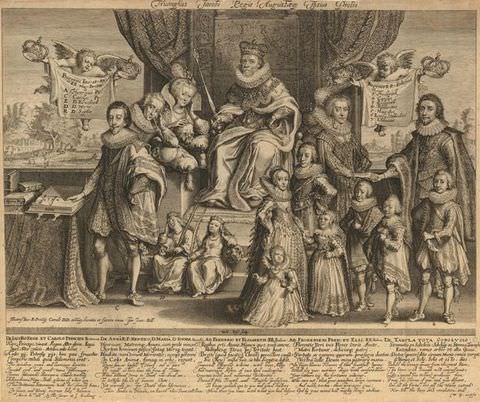

Willem van de Passe’s engraving The Triumph of King James and His August Progeny, published in 1624, emphatically proclaims the national strength and stability afforded by the king’s peaceful rule (fig. 1).1 James, the founder of the new English royal line, sits elevated and enthroned, surrounded by two generations of his family. To the monarch’s right, his son Prince Charles stands in the foreground, his hand resting upon the King James Bible with his father’s compiled Workes positioned just behind. He is designated heir not only to the crown but also to the royal word.2 Gathered around the prince are his mother, Queen Anna, and his siblings, Prince Henry Frederick and the little Princesses Sophia and Mary, all of whom are represented despite their predeceasing the date of the engraving. Each of them holds a skull, their heads propped against their hands in a gesture signifying melancholy and death. The daughters grasp palm fronds, symbols of victory over mortality. Significantly, balancing this rather morbid grouping are James’s daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband, Frederick V, the exiled Elector Palatine and king of Bohemia, accompanied by their large and expanding brood of offspring. A line of symmetry runs down the engraving separating the two alternative branches originating from the royal stem of King James. Whereas Charles is portrayed as upholding the king’s legacy of prudent policy, Elizabeth is shown supporting his cultivated persona of royal progenitor. It is through her that Stuart images of family and fruitfulness are extended and the security of the line is ensured. This print is therefore a statement of constancy and progression. Despite family tensions, the dynasty is presented as a single unified entity, composed of all its members—living, deceased, and separated by distance. Here are the flourishing Stuarts of Great Britain but, at this point at least, it is the foreign branch of the family who represents the next stage in the royal succession.

1

James VI and I framed his monarchical prerogative in lineal terms, locating his power in the royal line that preceded him and, significantly, that proceeding from him.3 His patriarchal authority rested in the production of male heirs, stabilising and securing the succession. The king’s own children therefore promoted his fatherly authority, and images of them and of their own offspring reinforced his ideological construction of kingship.4 Accordingly, this article examines the dynastic and political significance of James’s Palatine descendants, early Stuart Britain’s second royal family. Crucially, following the birth of King James’s first grandson, Prince Frederick Henry, in 1614, and for the next sixteen years, until the birth of a healthy son to King Charles I and his consort, Queen Henrietta Maria, the multiplying Palatine progeny represented the next generation of the Stuart line. More than that, they also served an important propagandistic role, bolstering political languages of family. Following the death of Henry, James’s elder son and heir, in 1612, Elizabeth’s forthcoming marriage assumed additional weight. Not only did it offer a lavish counter-attraction to the solemn mourning, shifting focus onto the future of the dynasty, but the newly-weds also became champions for the staunchly Protestant circles disappointed by the prince’s loss.5 It was important that this popular pair, once resident at Frederick’s court in Heidelberg, continued to cultivate ties with the British people and, as their family grew, encourage familiarity with the prospective royal line. A steady stream of printed images was enlisted in this campaign to introduce the public back home to the Palatine offspring. Through these depictions, distance was mitigated and audiences brought closer to their potential rulers. Jaroslav Miller has shown how cultural representations of Frederick and Elizabeth promoted both distinct nationalist sentiments and pan-European Protestant hopes.6 My discussion here assesses a further layer of entreaty, centring on the familial and the domestic. By materialising the international network of connections between Protestant princely courts in intimate terms, these prints evidence the reciprocal exchange and adaptation of dynastic imagery between Britain and the continent. Reflecting on Charles I’s imagery, Kevin Sharpe has observed that, throughout the personal rule, the promotion of the king’s family helped to foster affective connections between ruler and subject.7 Elsewhere, I have argued that this publicisation of domestic affairs originated with James, who promoted his family to forge emotional bonds with the public.8 Images of the Palatine family drew on and developed these early Stuart representational conventions well before Anthony Van Dyck revolutionised the depiction of royal domesticity. Tracing the development of the Palatine family’s portrayal according to the shifting fortunes of the couple, from their marriage to the death of King James, I shall explore how these representations sought to naturalise a foreign royal family, forging cross-European dynastic loyalties. Images of Elizabeth’s family, portrayed as lineal standby or perhaps even as an alternative, might endorse, or indeed complicate, dynastic rhetorics. As we shall see, the affective bonds encouraged by word and image actually risked straining family ties and public allegiances.

3Broken Lines: Dynastic Rupture and Repair

For James, the marriage of his daughter to one of the most prestigious secular princes of the Holy Roman Empire, and the head of the Protestant Union, represented a strategic move. Balancing a prospective Catholic match for his son and heir, Henry, the union was designed to calm religious tensions at home and abroad.9 Frederick had arrived at an English court alive with preparations for marital festivities and celebrations in mid-October 1612. All of that was to change towards the end of October, when it became clear that Prince Henry was seriously ill. On 9 November, three days after the prince’s death, Frederick accompanied his betrothed and the diminutive new heir, Prince Charles, to a consolatory meeting with the king.10 The elector’s attempts to offer support and solace appear to have impressed James, who then decided to take him to Royston, where the king chose to recuperate.11 This act of royal favour did not go unnoted and, as the mourning proceeded, Frederick played a prominent role. Although Prince Charles acted as principal mourner at Henry’s funeral, Frederick assumed the next place of precedence, with his high-ranking attendants also participating.12 Shortly after, on 18 December, the elector was invested as knight of the Order of the Garter, a symbolic link to the chivalric Prince Henry, which was strengthened further by the bestowal of the deceased prince’s diamond Lesser George and ribbon.13 During the Christmas day service in the chapel at Whitehall, Frederick was prayed for among the king’s children.14 This public assimilation of Frederick into the Stuart family unit was extended through the printed word. In Robert Allyne’s Funerall Elegies upon the Most Lamentable and Untimely Death of the Thrice Illustrious Prince Henry, a poetic lament was dedicated to each of Henry’s bereft family members, concluding with a verse directed at the elector himself. Designating the young Stuart siblings as “three great lights”, it reflects on the tragic dimming of “the greatest light that grac’d our day”.15 In Frederick, however, the author sees a new light; his proposed match offers a hopeful restoration of, and even a surrogate for, what has been lost:

916Yet doe great Prince for what thou mean’st to do,

Is but t’ingraft another with the two,

That three (though sundred) yet may no lesse shine,

O’re all the bounds betwixt the Thames and Rhine.16

Similarly, Edward Chetwynd’s sermon Votiuæ Lachrymæ is dedicated to Charles, Elizabeth, and Frederick together. Chetwynd entreats that “you would always set before your eies the Princely patterne of vertue and pietie, so happily expressed in the example of that blessed Soule, whom the world was no longer worthy to enjoy”.17

17With the marriage revels underway, these efforts to incorporate Frederick into the familial fold continued. It would appear that surprisingly few printed images were produced to celebrate the nuptials—the representational focus, at this point at least, was firmly centred on courtly spectacle and performance. Of the prints that were created, however, Renold Elstrack’s fine full-length engraving of the princely pair, pictorially integrates Frederick with the British royal dynasty. It was one of a series of three large engravings of Stuart couples executed by Elstrack, depicting Mary, Queen of Scots, and her husband, Henry, Lord Darnley; James VI and I and his queen, Anna of Denmark; and the newly-weds (fig. 2).18 Likely issued in close succession, these images together conveyed visual messages of dynastic stability and continuity. By depicting three royal generations, the series underlined the durability of both Stuart ancestry and posterity, subtly pointing to processes of recovery and succession against a backdrop of loss. These messages are reinforced by compositional similarities between the prints. In particular, the figures of Frederick and Elizabeth, presented as miniature models of the regal couple, correspond closely to those of James and his consort, with their placement, gestures, dress, and accessories deriving from those of their elders (fig. 3). Assuming a posture akin to his father-in-law’s, Frederick too sports a cape, ornate ruff, feathered hat, and Lesser George (by implication, that which had belonged to Prince Henry), while his wife, like her mother, is depicted slightly in the foreground, is arrayed in jewels, wears an elaborate farthingale skirt, and holds a prayer book and fan. These prints set an abiding process in motion, whereby the new electoral couple were incorporated into Stuart familial iconography. Frederick’s image was adopted and adapted to articulate reassuring messages of dynastic resilience and renewal.

18

First Impressions: An Infant’s Dual Inheritance

Of course, the early modern princely match was rarely an end in itself. Children validated their parents’ alliance, ensuring lineal and political stability. From the outset, the focus had been on the fruits of this union. In Great Brittaines Generall Joyes, a poem celebrating the Palatine marriage, for example, Anthony Nixon entreated that God

Rather controversially, the verses acknowledge the dynastic significance of the couple’s potential issue for both the Palatinate and Britain. Indeed, Elizabeth and her future family offered a reassuring reserve spot in the line of succession and, with concerns over the health of James’s new heir, the twelve-year-old Prince Charles, it was not unthinkable that she would one day succeed to her father’s throne. Certainly, following Henry’s demise, there was some resistance to the Palatine match and to the princess’s departure abroad for that very reason.20

20Elizabeth was actually pregnant before she left England and, while news slowly filtered back home that the new electress “wants not the concurrence of all such tokens and probabilities as are usually observed in women in that state”, the expectant mother herself declined to discuss her condition.21 She dismissed approaches on the matter and did not appear to take precautions. Despite this, in early December 1613, a skilful English midwife, Mrs Mercer, reputed to have “an excellent good report, both for skill, carriage and religion”, was sent to Heidelberg to attend Elizabeth’s delivery.22 Unfortunately, she arrived too late—for on 2 January 1614 the elector’s chief physician, Christian Rumph, delivered Prince Frederick Henry of the Palatinate. Having underplayed her condition, Elizabeth was quick to realise the implications of this birth, writing to Charlotte Brabantina, duchess of La Trémoille and Thouars: “God grant that the son, which this bounty has given me, may one day, by this grace, bring all happiness which I desire to all his relations”.23 The German statesman Count Albert of Solms was more emphatic in his celebratory letter to Sir Thomas Lake, remarking: “I rejoice to see this young and beautiful plant in which Germany and Great Britain have participated (the one for the conception the other for the birth). One doubts which of the two should be called the true homeland”.24 Certainly, bells and bonfires greeted reports of the prince’s birth in his mother’s native country.25 What is more, when Parliament met in April, King James’s opening speech revived his preferred patriarchal imagery, referencing his new status as grandsire:

2126Since the last p[arlia]ment, I have had for my sinnes and the peoples, taken away one and the first branch thereof. But as the Lord gave me the afflictions of Job so he hath given me the patience & the reward; an other for him, a grand-child in his place … I maye saye the Lord hath taken and hath given.26

Perhaps most significantly, one of the few achievements of this ineffectual sitting, later dubbed the Addled Parliament, was the passing of a bill proclaiming Elizabeth and her children by Frederick or “otherwise” next in line to the crown after her father and brother. As George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury, reported, it also made orders “for the naturalizing of the Count Palatine himselfe, and his children by that lady, throughout all generations, so they are now capable of any good fortune or preferment here”.27

27

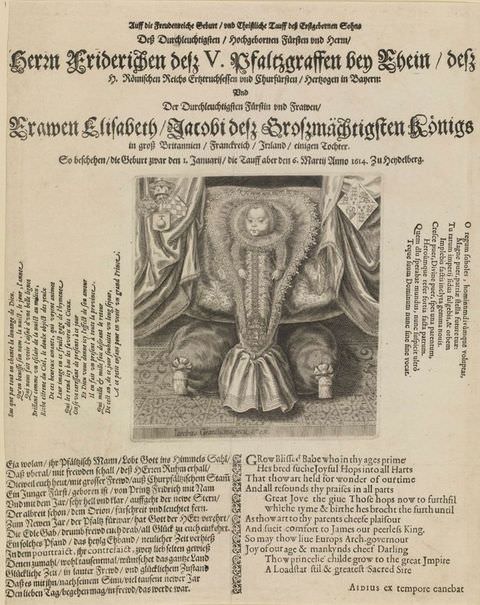

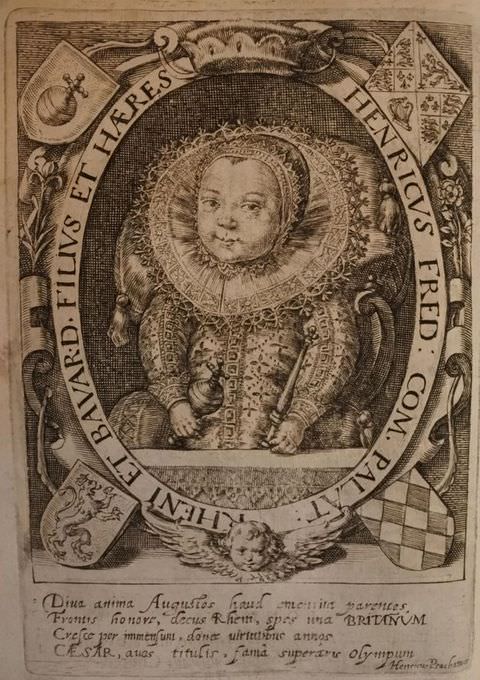

This process of naturalisation was pictorially extended in a remarkable engraving, probably the first executed of the new Palatine prince (fig. 4). Produced in Heidelberg by Jacques Granthomme, it illustrates a broadside celebrating the delivery of the elector’s firstborn son.28 The pan-European implications of this birth are demonstrated by the accompanying verses in German, French, Latin, and English. Presented between the heraldic escutcheons of his father and mother, the cherubic newborn addresses the viewer with a singularly precocious gaze. He is wrapped in jewel-encrusted swaddling bands, accessorised with elaborate lacework cap, ruffs, and cuffs. The decorative cover or long stay that encloses the infant is similar to the ornate whisks worn by adults and it is likely no coincidence that it resembles a heart. Frederick Henry is therefore presented as a shining gem, the bounty of his parents’ love. Propped on two cushions and framed by drapes on either side, the prince is also placed within an arrangement suggesting a child-appropriate throne and cloth of estate. These grand aspirations are echoed in the rather bombastic English verse that plays on contemporary predictions that the Palatine dynasty will one day be raised to the status of Holy Roman Emperors.29 In triumphantly prophetic terms echoing those that were applied to his uncle, the author foresees that this princely babe will dominate Europe:

28

Regal expectations were extended and accentuated in an adaptation of this image, produced as the frontispiece for Henry Peacham’s celebratory text Prince Henrie Revived, written in Utrecht but published in London the following year (fig. 5). The author frames his literary undertaking, dedicated to Elizabeth, as fulfilling a debt for her patronage, for “tak[ing] notice of me, and my labours”.31 Invoking the newborn’s deceased uncle, Peacham’s rather long-winded poem, cast the young prince as a “Phoenix” and “A new borne Henry”.32 Drawing attention to the infant’s international Protestant descent, the verses also presented his birth as a unifying moment:

3133Now Germanie, and Brittaine, shall be one,

In League, in Lawes, in Loue, Religion:

Twixt Dane, and English, English and the Scot,

Olde grudges (see) for euer are forgot.33

The accompanying engraving depicts him within a roundel, which is topped with the electoral cap and decorated with the heraldic insignia of his mother and father. He is now presented holding an orb-shaped rattle and a sceptre, with the Latin verses below proclaiming him “One hope of the Britons”. Frederick Henry’s first appearance in print is an appealing image of a bonnie babe, designed to promote familiarity with the latest addition to the Palatine and Stuart lines. More than that, however, in the original and copy, word and image combine to proclaim prodigious hopes, exploiting connections with the deceased Prince Henry while also hinting at a regal destiny. Elizabeth’s family was again used to heal the rift caused by the Stuarts’s recent loss, presented both as a source of regeneration and as the inheritors of the former Prince of Wales’s political and religious legacy. This publicity campaign, however, was not without its representational tensions, as it implicitly undermined the positions of Elizabeth’s relatives back home. To put forward the young Palatine prince as a potential British king was to tacitly acknowledge anxieties over Prince Charles’s health and the Stuart succession.34 Moreover, the advertisement of the Palatine match and its fruits threatened to destabilise James’s foreign policy. As the king pursued the next step in his conciliatory strategy to balance his daughter’s marriage, opposition was gathering at home. From the outset, Elizabeth’s union had been presented as a counter to Spanish Habsburg dominance.35 To those disillusioned by James’s increasing accommodation with Spain and a proposed alliance between Charles and the infanta Maria Anna, her robustly Protestant family represented an alternative focus for loyalty.36 Thus the promotion of the electoral couple and their children required careful navigation, offering opportunities both to support and to undercut dynastic programmes and propaganda.

34Royal Reproductions: Adapting the Palatine Prince

Just under four years later, Frederick Henry was provided with a sibling, when a second son, Charles Louis, was born in December 1617. Over the next few years, the Palatine nursery saw regular additions, with a daughter, Elizabeth, born in 1618 and two more sons, Rupert and Maurice, by early 1621. As her family grew, the electress sent a series of painted images home to the English court. Just three months after Frederick Henry’s birth, the Venetian ambassador reported that the king “has been much pleased with a portrait of the baby prince”.37 Five years later, in 1619, Elizabeth took advantage of a visit from Sir Henry Wotton, recalled from his Venetian embassy by the king, to send her father “the portraits of Your Majesty’s three little black babies”.38 The term “black babies” refers to the dark heads of hair with which all of her children were born. The transmission of paintings from Heidelberg to London presented opportunities for the Stuarts to control and adjust the broader messaging around the Palatine family. It seems likely that, around 1616, another full-length portrait of Frederick Henry was sent to his grandfather (fig. 6). It shows the princely toddler arrayed in elaborate lacework, his skirts and leading bands embroidered with gold fleur-de-lys and olive sprigs, echoed in the green and mauve embroidered furnishings and drapes. A lace cap sits on his angelic head, its crown embellished with feathers and a jewelled badge in the form of a shield, from which lances, arrows, and banners protrude. He wears a diamond chain over his shoulder, a large drop pearl extending from its monogram pendant that pointedly reverses his initials to read HF, recalling his Stuart uncle. The prince is shown at play, lighting a tiny gold toy cannon with his right hand. The portrait, an essay in gaudy ostentation, presents the toddler as treasured and precious. Balancing pacific and martial imagery, it also pictorially hints at the moderation that James himself had advocated to his own son in his princely treatise, Basilikon Doron: “as I have counselled you to be slow in taking on a warre, so advise I you to be slowe in peace-making”.39 In a flattering gesture, the composition therefore subtly presented the young prince as an inheritor of his grandfather’s pragmatic policy, while also connecting him to Prince Henry through his jewelled monogram.

37

An English engraving after the painting, however, omits these subtleties, neutralising any bellicose undertones. Francis Delaram’s adaptation simplifies sartorial details, obscures jewelled imagery, and pares back the prince’s surroundings, focusing instead on Frederick Henry’s sweet countenance (fig. 7). Its enduring appeal is demonstrated by a later Dutch copy, engraved by Claes Jansz. Visscher in the early 1620s.40 Most significantly, the composition replaces the miniature artillery with a tennis racquet and ball. Traditionally a sport of kings, tennis was considered a noble pastime that promoted an active body and good health.41 Again, James had advocated it to his heir as a “faire and pleasa[n]t” sport.42 Accordingly, the engraving reassuringly portrays Frederick Henry as hale and hearty without the potentially knotty martial assertions of the painted original. By doing this, it also distances the prince from his uncle’s increasingly idealised memory, which by now was not unproblematic for James.43 Early commemorative texts had begun to amplify Prince Henry’s militant Protestantism, presenting him as an exemplary prince whose values stood in contrast to those of the king.44 The rather clumsy verse that accompanies Delaram’s image follows its visual prompt, encouraging the reader to see a shining future in the prince’s features:

40Child-hood nere with majestie

agreed but in this Face and Eye

Shewing he shall, to raise his race

Be Greate and Gratious like his Face.

Less emphatic in tone than the verses that had greeted his birth, the lines predict a prudent path of moderation that will grow to distinguish his royal house. Likely executed with the assent of the court, Delaram’s image presents the Palatine prince in careful terms, aligning his image with Stuart representational concerns. It disassociates him from Prince Henry and cautiously celebrates the shoring up of Stuart stock, while avoiding references to an explicitly English inheritance. The royal infant’s portrayal has been made to conform to his grandfather’s dynastic programme.

Providential Proofs: Depicting Disaster and Destiny

As the Palatine family continued to grow, the political situation in the Holy Roman Empire approached crisis point. Following the deposition of Catholic Habsburg emperor, Ferdinand II, as king of Bohemia in 1618, Frederick had been elected to and had accepted the Bohemian throne in his place.45 In November 1619 Frederick and Elizabeth were crowned in Prague. The six-year-old Frederick Henry had accompanied his parents to their new capital and, in September 1620, progressed in great state through Bohemia and the Palatinate to Leeuwarden in the Netherlands.46 The journey was an opportunity to present Bohemia’s new heir to his subjects and, at the same time, to ensure that he was removed from the increasingly desperate state of affairs in the kingdom. Assuming a rebel crown was a risky business, and in August an imperial Habsburg army had marched into the Lower Palatinate. By October the Catholic League was advancing on Prague, and, on 8 November, Frederick’s troops were crushed at the Battle of White Mountain.47 With their new kingdom lost and their hereditary dominions soon to be confiscated as well, the Palatine exiles arrived at The Hague in the spring of 1621.48 Despite their ignominious flight, however, Frederick and Elizabeth, having forfeited all for the true faith, now became genuine Protestant champions. They assumed martyrlike status, with prayers, poems, and pamphlets praising their sacrifice. In 1620, for example, the Protestant polemicist Thomas Scott preached that their suffering had been inflicted by “Sathan and his associates”, employing familial imagery and comparing their trials to those of their biblical progenitor Job.49 The same year, the poet John Taylor addressed the English and Scots forces raised for the campaign in Bohemia, asserting that they fought “For God, for Natures, and for Nations lawes”. Taylor also highlighted the dynastic proximity of their cause:

45Elizabeth too exploited familial terms in her requests for aid, framing the hoped-for support from James as a demonstration of his “fatherly affection”.51 In the early years of their exile, the promise of further military reinforcements offered the chance of restitution.52 Newsbooks greeted these boons with optimistic predictions that “ther is great hope of recovery, & turning of fortunes wheele”.53 In this context, the displaced Palatine family was presented as a single front united in affliction, embodying strength in adversity and a sense of providential destiny.

51

Executed in this vein, Willem van de Passe’s engraving was to become a defining representation of the Palatine family (fig. 8). Published in 1621 by Thomas Jenner, it featured on both English and Dutch broadsides.54 It was also repeatedly appropriated and adapted throughout the 1620s, with new diminutive figures added to the composition as Elizabeth and Frederick’s fruitful marriage continued to produce more children.55 Here, the royal offspring take centre stage, flanked on either side by their parents, who wear the crowns of their lost territories. According to de Passe’s inscription, the family were drawn from life, indicating official approval of this image. It is possible that the engraver passed through The Hague on his way from Utrecht to London, where he established his workshop. The Palatine offspring though, were now dispersed between The Hague, Brandenberg, and Berlin. The print’s projection of family unity is, therefore, a fabrication. Befitting their status as dynastic props, the four sons are identified in the captions below, while the female child at her mother’s side is merely designated as “a daughter”. A battle rages in the distance, and behind Frederick’s figure can be discerned a city skyline, probably intended to be read as Prague’s. The royal family are illuminated by the holy rays of God in the form of a sun, inscribed with the tetragrammaton. Below, the angel of the Lord wields his sword, while the accompanying text, from the Book of Psalms, extends the Hebraic analogy: “His Enemies will I clothe with shame. But upon himselfe shall his crowne florish”.56 Exploiting more biblical parallels, Frederick is presented as a second King David, who has fought in God’s name and will eventually be restored to his own Jerusalem. Accordingly, both Frederick and his descendants will be supported on their thrones and afforded heavenly protection, while their adversaries will be confounded. Certainly, for those in any doubt about the righteousness of their cause, the verses below point to the visible proof of God’s approbation, the “princely progenie”:

54Thus Frederick and Elizabeth’s posterity are portrayed as a godsend, the instruments of future redress. Like the chosen people of Israel, the wandering royal children will eventually prevail against their oppressors and regain their estates. In this print, reassuring messages of lineal continuity have become declarations of divine sanction. Yet again, however, the portrayal of the Palatine family had the potential to undermine their Stuart kin. James had never hidden his disapproval of his son-in-law’s acceptance of the Bohemian throne, issuing orders that forbade public rejoicings and prayers for the new king and queen.58 Following their exile, Elizabeth’s father had favoured a diplomatic course in his efforts to intervene for the return of the Palatinate, although never entirely ruling out military action.59 His subjects, though, were becoming increasingly vocal in calling for troops to be sent to protect continental Protestant interests.60 James was, after all, the designated Defender of the Faith. Instead, as the situation worsened, the king affronted Protestant sentiment and refused to walk away from negotiations for the proposed match with Habsburg Spain.61 His actions provoked a marked cooling of relations between sovereign and subjects.62 Images of his grandchildren, therefore, represented an inferred criticism of royal policy, tugging on public heartstrings and hinting at a call to arms. They also insinuated a lack of religious conviction in the monarch, compared to his resolute relatives. In the absence of shared approaches and objectives, Britain’s royal family appeared divided.

58Misprints: Realigning Regal Policy

In the years leading to James’s death, as Prince Charles assumed a greater public and political role, Stuart foreign policy began to shift. The prince’s incognito journey to Spain in 1623, to personally collect his bride, had failed dismally. The subsequent break-up of marriage negotiations was greeted with acute relief by many in Britain and, for some—including Charles himself—the abandonment of an Anglo-Spanish alliance was viewed as the advent of Anglo-Spanish conflict.63 This growing consensus offered hope to the exiled Palatine brood, and those who argued for war once again invoked familial bonds to justify the use of force. Thomas Scott, now writing from the continent, asserted that the Habsburgs had forcefully dispossessed “the innocent infants[,] the grandchildren of the king of England”, and demanded: “is there not then just cause that the Father should by warre vindicate the honour of his Son?”64 When Parliament met in February 1624, James opened by seeking the advice of its members on the stalled Spanish treaties. The response was belligerent: the houses granted a huge subsidy on condition that negotiations with Spain ceased and in support of the anticipated anti-Habsburg conflict.65 Nevertheless, while the king promised that the aid would be devoted to securing the Palatinate by military intervention, he was not explicit about the terms of any martial action and he never actually broke diplomatic relations.66 Under heavy pressure, James continued to appreciate that peace was still in the best interests of his kingdoms. When a force was finally sent to the continent under the command of Ernst, count of Mansfeld, the mission was severely hampered by French non-cooperation and the king’s insistence that the army was not to advance on Spanish territories or soldiers. The troops, eventually reduced by disease and desertion, never saw combat.67 It was in this climate of unsettled impasse that James died on 27 March 1625.

63Among the commemorative verses and images that marked his demise was Majesties Sacred Monument, a broadside authored by Abraham Darcie that features an engraving by Robert Vaughan that unites Stuart father, son, and daughter pictorially (fig. 9). Adorned with a laurel crown and arrayed in royal robes, James reclines within a towering monument, gazing out at the viewer, his head resting in his hand—an animated effigy. The regalia sits before him, flanked by a lion and unicorn. Alastair Bellany has observed that the soaring pyramidal structure above replicates Inigo Jones’s catafalque for the king, the dome of which was decorated with female personifications of the royal virtues.68 However, a more direct source for the monument’s columned canopy, positioned just above the tomb chest, has been overlooked. The coffered arch, pillars, and heraldic devices all derive from the tomb of Elizabeth I, which had been engraved as part of Henry Holland’s portrait series Herωologia Anglica in 1620 (fig. 10). While this visual quotation may have been practical, it was also significant. The Elizabethan revival, which can be traced back to a few years after the queen’s death, glorified her memory and portrayed her reign as a golden age for the Protestant cause.69 To depict the deceased monarch within his predecessor’s funereal iconography is to subtly recast his legacy. It also exploits long-standing associations between Elizabeth Stuart and the Virgin Queen, cultivated by the younger Elizabeth as an expression of her own militant Protestantism.70 This revision of Jacobean pacifism is extended by the connected accessories of father and son. James’s left hand grips a scabbard, inscribed with a line from Virgil’s Aeneid, “et parcere subiectis” (to spare the conquered). His successor, Charles, positioned on the left, wearing a crown and his own royal robes, holds the unsheathed sword bearing the answering phrase, “debellare superbos” (to subdue the proud). The new king is therefore shown acting on his father’s intentions, with his bellicose foreign policy figured as a natural progression.71 Darcie’s verse confirms this impression: “Se then you Saints a brave Succeeding Son / Perfecting what a father left undoone”. On the other side of the monument, Elizabeth sits grieving, surrounded by her children. Her own accessory, a handkerchief, lends a chivalric undertone to her image and recalls the favours bestowed on knights before combat. Accordingly, the text asserts that her brother has undertaken to be her saviour, her husband being conspicuously absent. Charles vows: “Ile See thee once more as thou erst hast been / (As th’art anointed) reinvested Queene”.72 Overhead in the heavens, and surrounded by a starry throng of recently deceased nobility, the souls of James and his queen, Anna, look on approvingly. Thus, in this final dynastic image, the Stuarts are represented sharing a common purpose. Charles is pictured fulfilling his domestic duty and sibling obligation. James’s own outlook, however, has been obscured, recast in line with his son’s policy of military engagement. His aims have been extended beyond the recovery of the Palatinate to the restoration of the Bohemian throne. The late king’s preferred familial imagery, if not wholly subverted, has been co-opted and remodelled according to his children’s interests. We see a dynasty outwardly united but concealing significant internal tensions.

68

Conclusion

As familial relations merged with international relations, the promotion of Britain’s second royal family was to prove contentious. From the outset, the Palatine match had been employed to support familial imagery, with the elector promptly assimilated into the Stuart fold. The dynastic disruption caused by Prince Henry’s death was met with reassuring representations of marital union that stressed lineal stability and progression. This process of pictorial naturalisation was advanced with the birth of a prince. The infant Frederick Henry was figured as the next stage in the Palatine and Stuart successions, a rising star who would adopt the political mantle of his deceased uncle. Yet the young prince’s inherited image posed problems for his Stuart grandfather. The great hopes invested in Frederick Henry threatened to overshadow those of the actual heir, Prince Charles, while the growing Protestant emphasis in portrayals of the Palatine family undermined James’s conciliatory foreign policy. The Stuart court responded by attempting to moderate and control divisive dynastic messages but met with limited success and the promotion of the Palatine couple and their children gained new momentum. Elizabeth and Frederick assumed heroic status following the loss of their new Bohemian territories, the confiscation of their hereditary Palatinate lands, and their escape into exile. They were celebrated as committed champions of the true faith and their growing family promoted as a sign of their rectitude. King James’s contrasting inaction and lack of fatherly care were implicitly criticised, and his continuing pursuit of a marriage alliance with Spain decried as a betrayal of familial bonds. Following the death of the king, the divergent images were realigned. Depictions of the Stuart dynasty fashioned an uneasy coalition by repositioning James in agreement with his children’s call to arms. James therefore suffered the consequences of his own success when it came to promoting domestic ties and dynastic bonds. The popularity of his daughter’s marriage, and its promulgation in print, had put family relations under pressure.

Conflicting and conflicted loyalties emerged during the next reign too. In the early years of Charles’s government, as David Cressy has shown, some dared wish the king’s sister onto his throne.73 Public sympathy for the Stuarts ran deep when personal tragedy struck in 1629. The premature death by drowning in the Haarlemmermeer of Frederick Henry, at just fifteen years of age, was mourned by the Palatine family’s supporters across Protestant Europe. Accordingly, Daniel Souterius’s Dakrua Basilika, or Princely Tears, ruminated on the prince’s demise in English, French, Dutch, and Latin.74 The Dutch clergyman’s pious consolation concluded with an awkward elegy that recalled those that had commemorated Prince Henry some sixteen years earlier. Souterius focused on the intense loss that “hath pearced in my brest” and that was only compounded by considering “what he in time / Might have attaind unto / in greatnes”.75 Similarly, the author of another elegy, published in London, portrayed the princes as a pair of stars, dimmed too soon but now shining brightly in heaven.76 Like his uncle, Frederick Henry was now connected with lost promise and vanquished hopes. Dynastic rupture was exacerbated by a communal sense of grief, and public relations with this foreign royal family had come to assume a degree of intimacy and investment. Even after the birth of the future Charles II in 1630, and the relegation of Elizabeth and her heirs from immediate succession, attachments and loyalties lingered. In 1644, as the Civil War raged, rumours circulated that Parliament hoped to make Elizabeth’s eldest surviving son, Charles Louis, a pretender king. Gerolamo Agostino, the Venetian ambassador, speculated: “the English contemplate setting up this prince in a position of dependency rather than of command … feeling sure that the people will consent easily, since the blood royal is not shut out”.77 While these reports amounted to nothing, they refer to the enduring bonds between the British public and the Palatine line. Indeed, when the Stuart dynasty eventually expired with the death of Queen Anne in 1714, it was Elizabeth’s Protestant descendants who acceded to the throne, after fifty-four Catholic heirs with stronger hereditary claims had been excluded. Propagandists for King George I and the Hanoverian succession frequently evoked his grandmother’s struggles and a familiar sense of divine deliverance. For example, Nathanael Harding’s sermon observed that the new monarch was “descended from the excellent Queen of Bohemia, who was (with her Royal Husband) so great and patient a Sufferer for the Protestant Religion”.78 Their forbearance had at last been rewarded, for “as a Kingdom was lost for Fidelity to the true Religion, so the Grandson of her who lost it, is because of his Religion, rewarded with far more considerable Dominions”.79 A new foreign dynasty was made more palatable by underlining its popular pedigree, in an echo of the providential messaging propounded during the Palatine couple’s early years of exile. Thus the promotion of Elizabeth’s lineage had long-lasting implications. Far from being collateral relatives or distant relations, the case of the Palatine family demonstrates the closely connected, often overlapping, impacts of family dynamics, dynastic politics, and affairs of state in early modern Europe.

73Acknowledgements

I would like to dedicate this article to the memory of my father, Dr. Peter John Murray, who passed away in October 2024. His encouragement and support were instrumental in my first and lasting engagement with Stuart family politics. It has not been lost on me that writing about a historical father–daughter relationship has assumed a special resonance, as my own relationship takes a new turn.

About the author

-

Catriona Murray is Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. She is a specialist in the art, objects, and performances of the Tudor and Stuart courts and has published widely on topics from seventeenth-century print culture to nineteenth-century historiography. Her first book, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity (Routledge, 2016), explored the strategic promotion of royal familial imagery as a compelling but ultimately precarious art of political communication. She is currently completing her second book, which considers the Stuart dynasty’s involved relationship with statuary and monuments, analysing how sculpture served to mediate royal authority, public loyalty, and political opposition.

Footnotes

-

1

Catriona Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity (London: Routledge, 2017), 109. ↩︎

-

2

Jonathan Goldberg, “Fatherly Authority: The Politics of Stuart Family Images”, in Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe, ed. Margaret W. Ferguson, Maureen Quilligan, and Nancy J. Vickers (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 12. ↩︎

-

3

Goldberg, “Fatherly Authority”, 4. ↩︎

-

4

Kevin Sharpe, Image Wars: Promoting Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660 (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 100; Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics, 4. ↩︎

-

5

Graham Parry, The Golden Age Restor’d: The Culture of the Stuart Court, 1603–42 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1981), 95–97; Thomas Pert, The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War: Experiences of Exile in Early Modern Europe 1632–1648 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 24. ↩︎

-

6

Jaroslav Miller, “Between Nationalism and European Pan-Protestantism: Palatine Propaganda in Jacobean England and the Holy Roman Empire”, in The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, ed. Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013), 62. See also Jaroslav Miller, “The Henrician Legend Revived: The Palatine Couple and Its Public Image in Early Stuart England”, European Review of History 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2004): 305–31. ↩︎

-

7

Sharpe, Image Wars, 276. ↩︎

-

8

Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics, 4, 17, 34, passim; Catriona Murray, “James VI and I and the Pageantry of Fatherhood”, in Art and Court of King James VI and I, ed. Kate Anderson (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025), 29–39. ↩︎

-

9

Nadine Akkerman, “Semper Eadem: Elizabeth Stuart and the Legacy of Queen Elizabeth I”, in The Palatine Wedding of 1613, 146–47; Malcolm Smuts, “The Making of Rex Pacificus: James VI and I and the Problem of Peace in an Age of Religious War”, in Royal Subjects: Essays on the Writings of King James VI and I, ed. Daniel Fischlin and Mark Fortier (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2002), 379; Pert, The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War, 23. ↩︎

-

10

Thomas Birch, The Court and Times of James the First (London: Henry Colburn, 1848), 205. ↩︎

-

11

The Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 2, ed. Norman Egbert McClure (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939), 391. ↩︎

-

12

The Funerals of the High and Might Prince Henry, Prince of Wales (London: John Budge, 1613), sigs. C1r–C1v. ↩︎

-

13

Carola Oman, The Winter Queen: Elizabeth of Bohemia (London: Phoenix Press, 2000), 69. ↩︎

-

14

Oman, The Winter Queen, 74. ↩︎

-

15

Robert Allyne, Funerall Elegies upon the Most Lamentable and Untimely Death of the Thrice Illustrious Prince Henry (London: John Budge, 1613), sig. B4r. ↩︎

-

16

Allyne, Funerall Elegies, sig. B4r. ↩︎

-

17

Edward Chetwynd, Votiuæ Lachrymæ: A Vow of Teares, for the Loss of Prince Henry (London: William Welby, 1612), sig. AA2v (emphasis original). ↩︎

-

18

Anthony Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 1603–1689 (London: British Museum, 1998), 46. See also Renold Elstrack, Mary, Queen of Scots, and Henry, Lord Darnley, circa 1613, engraving, 27.5 × 23.3 cm, British Museum, London, 1884,0412.16. ↩︎

-

19

Anthony Nixon, Great Brittaines Generall Joyes (London: Henry Robertson, 1613), sig. B2r. ↩︎

-

20

Oman, The Winter Queen, 67; Nadine Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 70. ↩︎

-

21

Letter from Thomas Lorkin to Sir Thomas Puckering, 8 July 1613, quoted in John Nichols, The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, vol. 2 (New York: AMS Press, 1828), 671. See also Oman, The Winter Queen, 125; Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, 101. ↩︎

-

22

Letter from Thomas Howard, Earl of Suffolk, to Sir Thomas Lake, 8 December 1613, quoted in Oman, The Winter Queen, 130. The emphasis on Mrs. Mercer’s integrity and faith reflects masculine anxieties over the intimate authority of midwives. See David Cressy, Birth, Marriage, and Death: Ritual, Religion and the Life Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 62. ↩︎

-

23

The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, vol. 1, ed. Nadine Akkerman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 134. ↩︎

-

24

Albert, Count of Solms, to Sir Thomas Lake, 6 January 1614, The National Archives, London, SP81/13, fol. 8r. ↩︎

-

25

Oman, The Winter Queen, 133. ↩︎

-

26

“Flowers of Grace: Or the Speache of our Souveraign Lord King James 5th April in 1614. At the session of Parliament then Begunne”, Cotton MS Titus C VII, fol. 122r, British Library, London. ↩︎

-

27

Archbishop Abbot to Sir Dudley Carleton, 21 April 1614, SP14/77, fol. 16r, The National Archives, London. Before James’s own accession, there had been debates over his alien status and the legality of his inheriting the crown as English property. Parliament was dissolved at the beginning of June so that the bill was never granted royal assent. ↩︎

-

28

Aidius, Auff die Freudenreiche Geburt vnd Christliche Tauff deß Erstgebornen Sohns Deß Durchleuchtigsten Hochgebornen Fürsten vnd Herrn Herrn Friderichen deß V. Pfaltzgraffen bey Rhein (Heidelberg, 1614), single sheet. ↩︎

-

29

Miller, “Between Nationalism and European Pan-Protestantism”, 69. ↩︎

-

30

Aidius, Auff die Freudenreiche Geburt vnd Christliche Tauff deß Erstgebornen Sohns. ↩︎

-

31

Henry Peacham, Prince Henrie Revived (London: W. Stansby, 1615), sig. A2r. ↩︎

-

32

Peacham, Prince Henrie Revived, sigs. B1r, B2r. ↩︎

-

33

Peacham, Prince Henrie Revived, sig. B3r–v. ↩︎

-

34

Concerns over Charles’s constitution in childhood continued into his adolescence. In his autobiography, Sir Simonds d’Ewes recalled that, following the death of Henry, Prince of Wales, his younger brother was “so young and sickly, as the thought of their enjoying him did nothing at all [to] alienate or mollify the people’s mourning”. James Orchard Halliwell, The Autobiography and Correspondence of Sir Simonds d’Ewes, vol. 1 (London: Richard Bentley, 1845), 49. Four years later, after his creation as Prince of Wales, Charles’s health was still causing disquiet. William Beecher reported that the courtiers were “whispering that they discover in him, somewhat a weak and crasie disposition”. William Beecher to Sir Dudley Carleton, 9 November 1616, The National Archives, London, SP14/89, fol. 41r. ↩︎

-

35

Calvin F. Senning, Spain, Rumor, and Anti-Catholicism in Mid-Jacobean England: The Palatine Match, Cleves and the Armada Scares of 1613 and 1614 (New York: Routledge, 2019), 133–39. ↩︎

-

36

By mid-1614, James was pursuing informal negotiations for a marriage alliance with Spain. Alistair Bellany, The Politics of Court Scandal in Early Modern England: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603–1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 63–65. ↩︎

-

37

Calen**dar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in the Other Libraries of Northern Italy, vol. 13, 1613–1615 (London: Mackie for His Majesty’s Stationery Office), 107. ↩︎

-

38

The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, 197–98. The portrait is almost certainly that held by the Royal Collection and attributed to the German School, Frederick Henry, Charles Louis and Elizabeth: Children of Frederick V and Elizabeth of Bohemia, 1619, oil on canvas, 135.3 × 140 cm, RCIN 404329. ↩︎

-

39

James VI and I, Basilikon Doron (Edinburgh: Robert Waldegrave, 1599), 71. ↩︎

-

40

See Claues Jansz. Visscher, Frederick Henry, First-Born Son of Frederick V, Count Palatine of the Rhine and King of Bohemia, circa 1621, engraving, Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Germany, P-Slg AB 3.1325. ↩︎

-

41

Gervase Markam, Countrey Contentments (London: R. Jackson, 1615), 109. ↩︎

-

42

James VI and I, Basilikon Doron, 121. ↩︎

-

43

Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics, 83–84. ↩︎

-

44

Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics, 146. ↩︎

-

45

Pert, The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War, 25. ↩︎

-

46

Akkerman, Elizabeth Stuart, 143–44. See also the printed account of the prince’s progress, A Journall of the Voyage of the Young Prince Fredericke Henry, Prince of Bohemia, Taken in the Sixt Yeare of his Age, from Prague in Bohemia to Luerden in Friesland (London: Nathaniel Butter and Nicholas Bourne, 1623). ↩︎

-

47

Pert, The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War, 28. ↩︎

-

48

Pert, The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War, 31. ↩︎

-

49

Thomas Scott, The Projector. Teaching a Direct, Sure and Ready Way to Restore the Decayes of Church and State (London, 1623), 39. ↩︎

-

50

John Taylor, An English-mans Love to Bohemia (London: George Eld, 1620), 2. ↩︎

-

51

The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, 307. ↩︎

-

52

Ronald G. Asch, “1618–1629”, in The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years’ War, ed. Olaf Asbach and Peter Schröder (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), 132. ↩︎

-

53

Good Newes for the King of Bohemia? (London, 1622), 5. See also More Newes from the Palatinate; and More Comforte to Every True Christian that Either Fauoureth the Cause of Religion, or Wisheth Well to the King of Bohemia’s Proceedings (London, 1622), 10. ↩︎

-

54

Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 63–65. ↩︎

-

55

See for example, the engraving after Willem van de Passe with additions, The Family of Frederick and Elizabeth, King and Queen of Bohemia, circa 1622, engraving, British Museum, London, 1891,0414.163; Claes Jansz. Visscher, The Family of Frederick and Elizabeth, King and Queen of Bohemia, circa 1626, engraving, British Museum, London, G,6. 129; After Willem van de Passe with additions, The Family of Frederick and Elizabeth, King and Queen of Bohemia, circa 1628, engraving, British Museum, London, 1848,0911.297. A woodcut after the engraving was also registered with the Stationers’ Company on 20 September 1621. Griffiths, The Print in Stuart Britain, 65. ↩︎

-

56

Psalm 132:18. ↩︎

-

57

The True and Lively Pourtraiture of the Most Illustrious Prince Fredericke, by the Grace of God, King of Bohemia, Count Palatine of the Rhine etc. (London: Thomas Jenner, 1621), single sheet. ↩︎

-

58

W.B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 303; Oman, The Winter Queen, 187. ↩︎

-

59

Patterson, King James VI and I, 306. ↩︎

-

60

Cyndia Susan Clegg, Press Censorship in Jacobean England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 161–62. ↩︎

-

61

Smuts, “The Making of Rex Pacificus”, 382. ↩︎

-

62

Thomas Cogswell, “England and the Spanish Match”, in Conflict in Early Stuart England: Studies in Religion and Politics, 1603–1642, ed. Richard Cust and Anne Hughes (London: Longman: 1989), 115. ↩︎

-

63

Cogswell, “England and the Spanish Match”, 127. ↩︎

-

64

Thomas Scott, Certaine Reasons and Arguments of Policie, Why the King of England Should Hereafter Give Over all Further Treatie, and Enter into Warre with the Spaniard (London, 1624), sigs. B2r, B4v. ↩︎

-

65

Patterson, King James VI and I, 347. ↩︎

-

66

Patterson, King James VI and I, 352. ↩︎

-

67

Patterson, King James VI and I, 355; Pert, The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War, 38. ↩︎

-

68

Alastair Bellany, “Writing the King’s Death: The Case of James I”, in Stuart Succession Literature: Moments and Transformations, ed. Paulina Kewes and Andrew McRae (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 54. ↩︎

-

69

Julia M. Walker, “Bones of Contention: Posthumous Images of Elizabeth and Stuart Politics”, in Dissing Elizabeth: Negative Representations of Gloriana, ed. Julia M. Walker (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), 257; Akkerman, “Semper Eadem”, 151. ↩︎

-

70

Akkerman, “Semper Eadem”, 160. ↩︎

-

71

Bellany, “Writing the King’s Death”, 55. ↩︎

-

72

Abraham Darcie, Majesties Sacred Monument (London: George Humble, 1625), single sheet. ↩︎

-

73

David Cressy, Dangerous Talk: Scandalous, Seditious and Treasonable Speech in Pre-Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 164–65. ↩︎

-

74

Daniel Souterius, Dakrua Basilika, That Is the Princely Teares of Elisabetha, Queen of Bohemia: Over the Death of Her Eldest Sonne, Fridericus Henricus (Haarlem: Harman Cranepoel, 1629). ↩︎

-

75

Souterius, Dakrua Basilika, sigs. C2v–C3v. ↩︎

-

76

R. Abbey, An Elegie upon the Most Deplorable Death of Prince Henry (London: Richard Roystore, 1629), single sheet. ↩︎

-

77

Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in the Other Libraries of Northern Italy, Vol. 27, 1643–1647 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1926), 130. ↩︎

-

78

Nathanael Harding, The Peoples Part in Blessing Their King (London: John Clark, 1715), 26. ↩︎

-

79

Harding, The Peoples Part in Blessing Their King, 26–27. See also Joseph Acres, Glad Tidings to Great Britain (London: John Clark, 1715); Thomas Simmons, The King’s Safety, The Church’s Triumph (London: E. Matthews and J. Harrison, 1715). ↩︎

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Abbey, R. An Elegie upon the Most Deplorable Death of Prince Henry. London: Richard Roystore, 1629.

Acres, Joseph. Glad Tidings to Great Britain. London: John Clark, 1715.

Aidius. Auff die Freudenreiche Geburt vnd Christliche Tauff deß Erstgebornen Sohns Deß Durchleuchtigsten Hochgebornen Fürsten vnd Herrn Herrn Friderichen deß V. Pfaltzgraffen bey Rhein. Heidelberg, 1614.

Allyne, Robert. Funerall Elegies upon the Most Lamentable and Untimely Death of the Thrice Illustrious Prince Henry. London: John Budge, 1613.

British Library, London. Cotton MS Titus C VII. “Flowers of Grace: Or the Speache of our Souveraign Lord King James 5th April in 1614. At the session of Parliament then Begunne”.

Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in the Other Libraries of Northern Italy. Vol. 13, 1613–1615. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1907.

Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in the Other Libraries of Northern Italy. Vol. 27, 1643–1647. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1926.

Chamberlain, John. The Letters of John Chamberlain. Vol. 2. Edited by Norman Egbert McClure. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939.

Chetwynd, Edward. Votiuæ Lachrymæ: A Vow of Teares, for the Loss of Prince Henry. London: William Welby, 1612.

Darcie, Abraham. Majesties Sacred Monument. London: George Humble, 1625.

The Funerals of the High and Might Prince Henry, Prince of Wales. London: John Budge, 1613.

Good Newes for the King of Bohemia?. London, 1622.

Harding, Nathanael. The Peoples Part in Blessing Their King. London: John Clark, 1715.

James VI and I. Basilikon Doron. Edinburgh: Robert Waldegrave, 1599.

A Journall of the Voyage of the Young Prince Fredericke Henry, Prince of Bohemia, Taken in the Sixt Yeare of His Age, from Prague in Bohemia to Luerden in Friesland. London: Nathaniel Butter and Nicholas Bourne, 1623.

Markam, Gervase. Countrey Contentments. London: R. Jackson, 1615.

More Newes from the Palatinate; and More Comforte to Every True Christian that Either Fauoureth the Cause of Religion, or Wisheth Well to the King of Bohemia’s Proceedings. London, 1622.

The National Archives, London. State Papers Domestic, James I. 1614, SP14/77; 1616, SP14/89.

The National Archives, London. State Papers Foreign, German States, James I. 1614, SP81/13.

Nichols, John. The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First. Vol. 2. New York: AMS Press, 1828.

Nixon, Anthony. Great Brittaines Generall Joyes. London: Henry Robertson, 1613.

Peacham, Henry. Prince Henrie Revived. London: W. Stansby, 1615.

Scott, Thomas. Certaine Reasons and Arguments of Policie, Why the King of England Should Hereafter Give Over All Further Treatie, and Enter into Warre with the Spaniard. London, 1624.

Scott, Thomas. The Projector. Teaching a Direct, Sure and Ready Way to Restore the Decayes of Church and State. London, 1623.

Simmons, Thomas. The King’s Safety, the Church’s Triumph. London: E. Matthews and J. Harrison, 1715.

Souterius, Daniel. Dakrua Basilika, That Is the Princely Teares of Elisabetha, Queen of Bohemia: Over the Death of Her Eldest Sonne, Fridericus Henricus. Haarlem: Harman Cranepoel, 1629.

Stuart, Elizabeth. The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia. Vol. 1. Edited by Nadine Akkerman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Taylor, John. An English-mans Love to Bohemia. London: George Eld, 1620.

The True and Lively Pourtraiture of the Most Illustrious Prince Fredericke, by the Grace of God, King of Bohemia, Count Palatine of the Rhine etc. London: Thomas Jenner, 1621.

Secondary Sources

Akkerman, Nadine. Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Akkerman, Nadine. “Semper Eadem: Elizabeth Stuart and the Legacy of Queen Elizabeth I”. In The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, edited by Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade, 145–68. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013.

Asch, Ronald G. “1618–1629”. In The Ashgate Research Companion to the Thirty Years’ War, edited by Olaf Asbach and Peter Schröder, 127–37. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

Bellany, Alistair. The Politics of Court Scandal in Early Modern England: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603–1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Bellany, Alastair. “Writing the King’s Death: The Case of James I”. In Stuart Succession Literature: Moments and Transformations, edited by Paulina Kewes and Andrew McRae, 38–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Birch, Thomas. The Court and Times of James the First. London: Henry Colburn, 1848.

Clegg, Cyndia Susan Press Censorship in Jacobean England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Cogswell, Thomas. “England and the Spanish Match”. In Conflict in Early Stuart England: Studies in Religion and Politics, 1603–1642, edited by Richard Cust and Ann Hughes, 107–33. London: Longman, 1989.

Cressy, David. Birth, Marriage, and Death: Ritual, Religion and the Life Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Cressy, David. Dangerous Talk: Scandalous, Seditious and Treasonable Speech in Pre-Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Goldberg, Jonathan. “Fatherly Authority: The Politics of Stuart Family Images”. In Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe, edited by Margaret W. Ferguson, Maureen Quilligan, and Nancy J. Vickers, 3–32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Griffiths, Antony. The Print in Stuart Britain, 1603–1689. London: British Museum, 1998.

Halliwell, James Orchard. The Autobiography and Correspondence of Sir Simonds d’Ewes. Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley, 1845.

Miller, Jaroslav. “Between Nationalism and European Pan-Protestantism: Palatine Propaganda in Jacobean England and the Holy Roman Empire”. In The Palatine Wedding of 1613: Protestant Alliance and Court Festival, edited by Sara Smart and Mara R. Wade, 61–81*.* Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2013.

Miller, Jaroslav. “The Henrician Legend Revived: The Palatine Couple and Its Public Image in Early Stuart England”. European Review of History 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2004): 305–31.

Murray, Catriona. Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity. London: Routledge, 2017.

Murray, Catriona. “James VI and I and the Pageantry of Fatherhood”. In Art & Court of King James VI and I, edited by Kate Anderson, 29–39. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025.

Oman, Carola. The Winter Queen: Elizabeth of Bohemia. London: Phoenix Press, 2000.

Parry, Graham. The Golden Age Restor’d: The Culture of the Stuart Court, 1603–42. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1981.

Patterson, W.B. King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Pert, Thomas. The Palatine Family and the Thirty Years’ War: Experiences of Exile in Early Modern Europe 1632–1648. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Senning, Calvin F. Spain, Rumor, and Anti-Catholicism in Mid-Jacobean England: The Palatine Match, Cleves and the Armada Scares of 1612–1613 and 1614. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Sharpe, Kevin. Image Wars: Promoting Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Smuts, Malcolm. “The Making of Rex Pacificus: James VI and I and the Problem of Peace in an Age of Religious War”. In Royal Subjects: Essays on the Writings of King James VI and I, edited by Daniel Fischlin and Mark Fortier, 371–87. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2002.

Walker, Julia M. “Bones of Contention: Posthumous Images of Elizabeth and Stuart Politics”. In Dissing Elizabeth: Negative Representations of Gloriana, edited by Julia M. Walker, 252–76. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/cmurray |

| Cite as | Murray, Catriona. “Distant Relations: The Palatine Family, Propaganda, and Print in Early Stuart Britain.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/cmurray. |