Papering over Division? James VI and I’s Misleading Materialisation of Union

Papering over Division? James VI and I’s Misleading Materialisation of Union

-

Anna Groundwater

-

Catriona Murray

-

Tracey Hill

-

Jane Ohlmeyer

-

David A. H. B. Taylor

-

Clare Jackson

-

Steve Murdoch

-

Cameron Maclean

-

John Peacock

-

Charlie Spragg

Provocation by

-

Anna GroundwaterPrincipal Curator, Renaissance and Early Modern HistoryNational Museums Scotland

In 1603 the Scottish king, James VI, succeeded to Elizabeth I’s thrones of England, Ireland, and Wales, uniting them with the formerly independent Scotland in the Union of the Crowns. James VI and I, as he now was, embodied the dynastic union, for it was made in his person only, in his kingship of all the British Isles. A year later, this reconfiguration of separate kingdoms into a single composite monarchy was celebrated in the creation of a resplendent hat jewel, named in an inventory of 1606 as the “Mirror of Great Britain”.1 Dominating James’s large black plumed hat, the jewel was captured for posterity by John de Critz in 1604 in his portrait of the new “British” king (fig. 1).2 Much like the light reflected from its faceted diamonds and glittering gold setting, the jewel was to “mirror” the glorious realisation of James’s long dreamed-of imperium.

1

More than this, the jewel materialised the unificatory process of the Union of the Crowns in its soldering together of gemstones from different nations, including stones retrieved from Elizabeth I’s jewellery, and a diamond from the Great H jewel given to Mary, Queen of Scots, by her father-in-law, Henri II of France.3 Through the remounting of the Tudor queen’s jewels and their uniting with one owned by her Scottish rival, the Stuart queen, the Mirror reflected the reshaping of Britain. Where the Great H had embodied the “auld” Franco-Scottish alliance, the hat jewel in this new configuration materialised a political realignment away from Catholic France and towards Protestant England, which helped to foster union within Britain. It symbolised James’s dual inheritance and cemented the idea of union.

3However, the unity suggested by the materiality of the jewel’s conjoined parts was misleading. By 1608, James had failed to achieve the fuller political union he had planned, with ongoing structural, political, and religious tensions manifested in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms of the 1640s. The Mirror, a composite object stuck together by James, came unstuck and was broken up and sold off by his son Charles.

This apparent legacy has all too often been read backwards, with the failings of Charles seen as originating in those of his father. Until the later twentieth century, James was judged through uncritical and too literal readings of his own writings, parliamentary records, and personal diaries. Too often, the latter have been English sources, frequently resistant to a union in which James intended Scotland and England to be co-equal. Particularly and lastingly insidious was the poisonous pen portrait attributed to a disaffected English courtier, Sir Anthony Weldon, in The Court and Character of King James, published in 1650 in the aftermath of Charles’s execution. This version of James was embraced by scholars such as David Willson in his influential 1956 biography of James and resonates still in popular literary and theatrical portrayals.4

4More recently, however, there has been greater acknowledgement of the strengths of James’s kingship, particularly in Scotland prior to 1603.5 However, less attention has been given in English and British historiography to the quality and legacy of his kingship in the newly configured “Great Britain” after the Union of the Crowns. A call from his foremost historian Jenny Wormald for a better understanding of the challenges of James’s multiple kingship after 1603 remains unheeded.6

5What I am suggesting here is that material and visual culture offer the potential for reframing the existing historiography of James’s post-1603 reign. Understanding of that period was previously predicated largely on the textual evidence described here. In contrast, the articulation of union in non-textual media offers an alternative lens through which to view James’s political objectives, which takes us beyond the Anglocentric archives. In the contested and negotiated representation of the new Britain in the early 1600s, such visual and material expressions also suggest the resistance James encountered. These tensions have resonated in succeeding centuries. The legacy of James’s disjointed Union of the Crowns is still visible today in the disputed extent of devolved legislative powers in Britain’s constituent parts.

James’s hopeful visual rhetoric of union was unachievable in reality. In 1603 he had one great project: to secure a fuller political union between England and Scotland than that achieved by the regnal union. Institutionally, England and Scotland remained separate. James alone was the nexus of a multiple monarchy in which both divergent and more concordant forces shaped relations between its unequally empowered parts. To bind England and Scotland together for the longer term, he needed the acquiescence of their parliaments and peoples to create a more “Perfect Union”, a union of “Hearts and Minds”.7 Its most ambitious envisaging saw the amalgamation of the parliamentary, judicial, and religious lives of his kingdoms. Problematically for James, these were very different.

7James knew well the efficacy of imagery in embedding the concept of union, and from the start of his English reign pursued a concerted cultural campaign to emblazon heraldic, emblematic, and iconographic motifs for his imperium over the four realms in diverse media, from coinage to banners and from paint to print. The iconography of Britain the brand was supposed to communicate, embody, and affirm what for James had already taken place within his own person. As he said to his first English Parliament in March 1604, the union was “made in my blood … as the head wherein that great Body is vnited”.8

8The materiality of objects that encapsulated and projected union seemed to suggest just that. Their components—from Asian rubies to Scottish gold—had disparate origins, and their creation was influenced by dynastic, political, and religious contexts and inflected by the cultural cross-fertilisation of the European Renaissance with English and Scottish traditions. These constituents brought together materialised unification to convince others of its reality. In an object such as the Mirror of Great Britain, what was implicit in its making was made explicit in its naming.

James was assisted by a long-standing cultural exchange between England and Scotland, a process that was strengthened following Protestant reformations in both countries. Equally for James, this was a Britain created within and by the Stuart dynasty, with its ancient lineage in Scotland and its hereditary claim to the Tudor succession through James’s great-great-grandfather Henry VII, whose name was inscribed on the second triumphal arch of James’s entry to the City of London in 1604, erected by the Italians.9 The Stuart kings themselves underwrote and embodied union and were to remain central to its materialisation. In their own terms, they were synonymous with the nationhood first of Scotland and then of the new Britain.

9

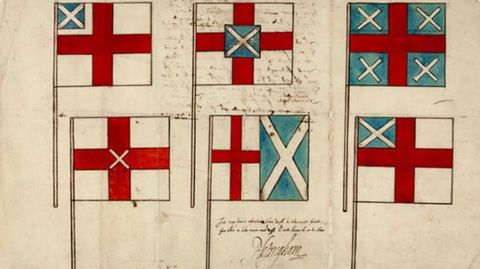

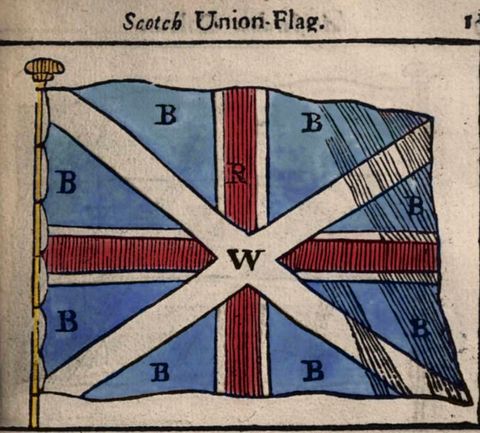

However, unease over the contested representation of the relative status of Britain’s nations is revealed by the iconography of the Union flag designs (fig. 2). The Scottish struggle for recognition of equal status was evident in this portrayal of the new partnership, as was England’s demonstration of its dominance within the union. This power play was also seen in the prioritisation of the Scottish lion rampant over the English three lions in the Scottish version of the Unite coin (fig. 3). In contrast, while the Irish harp was included in the Unite coinage, the failure to include Irish symbolism in the Union flag reflected James’s own physical experience of the union, in which Ireland was entirely absent. James might have seen himself as the father of one people, but representing that unity proved more difficult.

A more cohesive approach, however, was seen in differing versions of a “British” iconography. In particular, the conciliatory prioritisation of Scottish symbolism within Scotto-Britannic representations suggested how fears over parity could be addressed without upsetting the English. James’s first coinages in Ireland depicted the Irish harp alone on the reverse, but no attempt was made to reconfigure an Irish version of the British coat of arms on these coins. Was “coining” a British Ireland, demonstrating even greater tensions there, a step too far? In contrast, the greater integration of Welsh elites into the English Inns of Court and Parliament was materialised by the incorporation of Welsh silver into some English coins.10 The malleability of these expressions of Britain indicated how regnal union could be facilitated by accommodating each realm’s concerns.

10These negotiations point to expressions of soft power aimed both at garnering acceptance of fuller union and at countering resistance. This material evidence was thought to be significant then and remains so for today’s historians and politicians. James sought to envisage union as an already complete process of transformation, but his vision of equal partnership was simply too Scottish in its expectations. Inevitably this was to jar with an English version of Britain in which a distinct Scotland had been erased by the Elizabethan articulation of greater England.11 James’s visual rhetoric of union ultimately did no more than paper over ongoing divisions. A re-examination of the Union of the Crowns through its contested material expression reveals the insuperable challenges he faced.

11Response by

-

Tracey HillProfessor Emerita of Early Modern Literature and CultureBath Spa University

Figuring Britannia in Civic Pageantry

In 1603, to mark the accession of King James VI and I, the Merchant Taylors, one of the Great Twelve livery companies of the City of London, commissioned two new paintings from Thomas Scarlett for their hall on Threadneedle Street. Royal coats of arms were routinely displayed in company halls: on this occasion, though, the Merchant Taylors asked for paintings of St. George and St. Andrew. Scarlett was a very highly regarded painter and one whom they regularly employed, but his work was not well received this time: the company recorded in their accounts that he was given twenty shillings to “take back the picktures of St Georg & St Andrew bicause they were not liked”.12 This passing moment can be seen as an inauspicious start to the new king’s reign, as was—on a much larger scale—the severe outbreak of plague, which forced the postponement by a year of James’s coronation royal entry into London.

12There was another, more significant but equally unsuccessful, representation of the English and Scottish patron saints in James’s early days. Thomas Dekker began his book of the royal entry, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment, with an account of a hastily invented device that “should haue serued at his Majesties first accesse to the Cittie” at the bars at Bishopsgate, as “the first Offering of the Cities loue”. Costumed performers figuring St. George and St. Andrew were to “issue from two seuerall places on horse-backe and in compleate Armour”; they were also to bear “the arms of England and Scotland (as they are now quartered) to testifie their leagued Combination”.13 Dekker does not explain how this “quartering” of the arms of the newly united two kingdoms was to look. One wonders if England took precedence or if the arms resembled any of the Union flags designed in 1604. In any case, it was all wasted effort, for “his Majestie not making his Entrance (according to expectation)”, the whole device was “layd by” and nothing survives of any of it beyond Dekker’s description.14

13After this thwarted preamble, the royal entry proper finally took place on 15 March 1604. Following established tradition, the procession began at the Tower of London, a royal palace, and followed a route along Fenchurch Street, Gracechurch Street, Cornhill, down onto Cheapside, past St. Paul’s, across the Fleet to Fleet Street and Temple Bar, and from thence to Westminster. The king’s journey was punctuated by numerous pageant stations, most of which were highly decorated and elaborately carved arches—known as pegmes—with musicians and actors performing within or beside them. Contemporary images of the various arches were drawn up and published as The Arch’s [sic] of Triumph by the architect Stephen Harrison. Civic celebrations of the accession of a new monarch were mandatory, plague notwithstanding, and the City, its livery companies, and London’s resident “stranger” communities all expended large sums on the festivities. Of the seven arches erected within the City limits, two were set up under the aegis of the strangers: the Italian arch on Gracechurch Street and the Dutch arch on Cornhill. This again was not unusual; for the Dutch in particular, the start of a new reign was an opportunity to request continued protection from the sovereign. What was unusual, though, was James’s own status as a “stranger”, which was implicitly referred to in the putative pageant at Bishopsgate. St. George and St. Andrew, standing as representatives of their respective nations, Dekker writes, had for “a long time lookt upon each other, with countenance rather of meere strangers than of such neare neighbours”.15 The king’s role as London’s guest during the royal entry was therefore double-edged in a way that, for example, Queen Elizabeth’s in 1559 had not been. Indeed, despite James’s efforts to forge a thoroughgoing union, the Scots were still regarded as “strangers” in England into the 1630s.

15

James’s path to the English crown as Elizabeth’s heir and successor rested on their shared ancestry. His legitimacy derived ultimately from Henry VII, and this connection was staged explicitly in the Italian arch in the royal entry. King Henry was shown, in Dekker’s words, “royally seated in his Imperiall Robes”, holding a sceptre that was being presented to James on horseback, underneath the Latin motto “Hic vir, hic est” (fig. 4). In case these two kings were not easily recognisable to onlookers, “Iacobo Regi Magn” and “Henrici VII” were carved into the arch below.16 On the reverse side of the arch (not shown in Harrison’s book), “in most excellent colours [and] Antikely attir’d, stood the 4 kingdoms, England, Scotland, France and Ireland, holding hands together”.17 Wales, not being regarded as a separate kingdom in the early modern period, was tacitly incorporated into “England”.

16Concord and unity were the keynotes of the pageantry staged for James, although the imagery of nationhood it employed could appear strained. The fourth arch of the procession was located at the Great Conduit on Cheapside, the City’s major thoroughfare. It depicted “Felix Arabia”, “under which title”, wrote Harrison, “the whole Island of Britannia was figured”.18 “Arabia Britannia”, an imaginary hybrid, was in itself a strange choice of lead character for the device. Setting aside the further quibble that “Britannia” is only an island if Ireland is excluded, which is unlikely to have been the intention, the “interpretation” of what Dekker called “this dumbe Mysterie” was even more muddled. A chorister from St. Paul’s delivered the oration, in which James was named the “great Monarch of the West”, whose “triple Diadem” was even heavier than “that of [his] grand Grandsire Brute”. Furthermore, unlike the kings of old who bore laurel or gold crowns, James’s “garland” was composed of “the Red-rose and the White / With the rich Flower of Fraunce”—the Tudor rose and the French lily, but no flower of Scotland.19

18Commentators on and propagandists of James’s accession were faced with a conundrum that none could solve: to emphasise the monarch’s legitimacy and erase his Scottishness or to include emblems of Scotland such as St. Andrew and be met with indifference or latent hostility. No wonder the king’s treasured “Great Project” never came to fruition.

Response by

-

Jane OhlmeyerErasmus Smith's Professor of Modern HistoryTrinity College Dublin

Commercialisation, Colonisation, and Civility

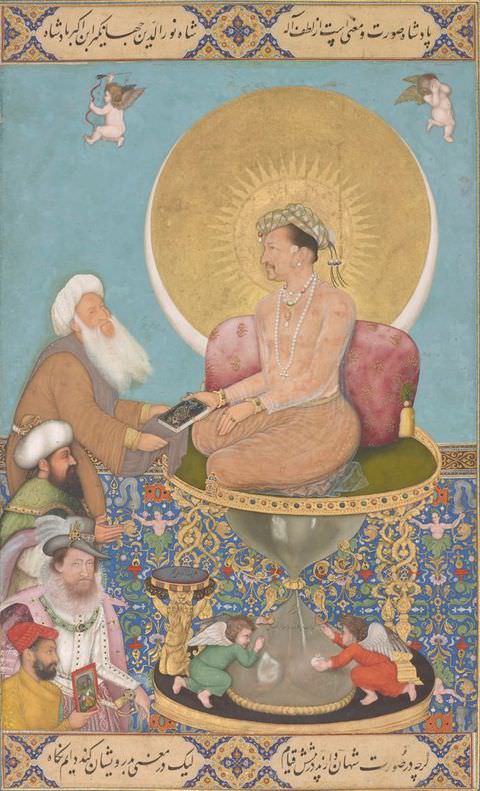

A remarkable Mughal miniature, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings by Bichitr, an artist who worked at Jahangir’s court, shows the emperor granting an audience to four men, who are lined up in order of their importance: first the Sufi mystic, then the Ottoman king, followed by King James VI and I of Great Britain and Ireland, and finally the artist himself (fig. 5). Bichitr based his representation of James on a portrait by the Flemish painter John de Critz that Thomas Roe, the first English ambassador to the Mughal court, had presented to Jahangir in 1615. This gift from Roe has been lost, but presumably it was a copy of De Critz’s 1604 so-called British portrait of James wearing his plumed hat with his famous hat jewel.

The likeness is striking even if Bichitr’s painting is lighter and is embellished with Mughal motifs. James wears his hat jewel, while pearls and other precious stones adorn his hat, cape, and tunic, and the belt that holds his jewel-encrusted sword (fig. 6). James, while dignified, is portrayed as an affluent supplicant rather than as a mighty sovereign with imperial ambitions of his own in Ireland and the Atlantic World. Given how inconsequential James and his remote kingdoms were to the Mughals, it is remarkable that Bichitr painted him at all. Perhaps the artist simply wanted to include some European curiosities—an hourglass, cherubs, along with a Christian king—to underscore the pre-eminence, confidence, and cosmopolitan nature of the Mughal Empire. The result is a powerful reminder of the reality of the world order at the turn of the seventeenth century but also of its interconnectedness as people traversed the globe in search of influence, knowledge, and riches.

While Roe’s diplomatic mission failed to secure trading privileges for the East India Company, which had been established as a corporate body in 1600, Jahangir permitted the company to establish a factory at Surat in 1619. From this modest foothold in Mughal India, the company expanded its influence, and thanks to trade, primarily in spices and later textiles, made fortunes for the Crown and its investors. It was with this profiteering mindset that James approached Ireland, determined to control, to commercialise, to “civilise”, and to colonise.20

20How did his Irish subjects respond to their new king? Literary scholars have shown how the accession of James to the crown of the three kingdoms was initially a source of joy and hope (Mary Stuart, his mother, was, after all, a Catholic).21 Contemporary poets recaptured this sense of optimism. A Donegal poet, Eoghan Ruadh Mac an Bhaird, held James to be Ireland’s legitimate monarch:

21Three crowns—'tis fitting for him—shall be placed on James’s head …

That young Prince so high of mind, James Stewart, shall have Ireland’s wondrous crown—an honour, I know, he well deserves …

The adoption of James as Ireland’s spouse by the Irish learned classes was reflected most vividly in the work of the genealogists, who created an impeccable Irish ancestry for him—as did other scholars. The Annals of the Four Masters, compiled by priests in Louvain, recounted the annals of the kingdom of Ireland, a kingdom ruled over by “the Crown”. With these poems and works of prose, a vocabulary of kingship—including words such as “writ”, “sovereign”, “majesty”, “commonweal”, and “crown”—entered the Irish language for the first time.23

23What then of Britishness? The efforts of James VI and I to create a so-called British state in Ireland fell far short of what he might have wished for. Over time some Protestant colonists described themselves as British. Most, however, touted their Englishness, as did the Catholic Old English of Norman descent, who had served as the Crown’s traditional supporters in Ireland. Only the Gaelic-speaking Catholics regarded themselves as Irish. But James could never fully trust his Catholic subjects, not even the Old English. In their place he consistently ennobled Protestant planters and promoted them to high administrative, judicial, and political office. With the conclusion of James’s only Irish Parliament in 1615, the active phase of his kingship in Ireland, which had begun only in 1606, ended.

During this decade, however, James consolidated the Crown’s position in Ireland. He established a level of political, administrative, and legal control over all elements of Irish society, and especially over the semi-autonomous Irish lords. He did what he could to secure religious conformity and to anglicise the apparently barbarous customs, practices, and culture of the Irish. Finally, official plantation in Ulster and unregulated colonisation across the island allowed him to transform the legal basis on which land was held in Ireland and to settle hundreds of thousands of (mostly Protestant) colonists on the island. These men and women brought with them the English language and English dress, social customs, and agricultural and business practices.

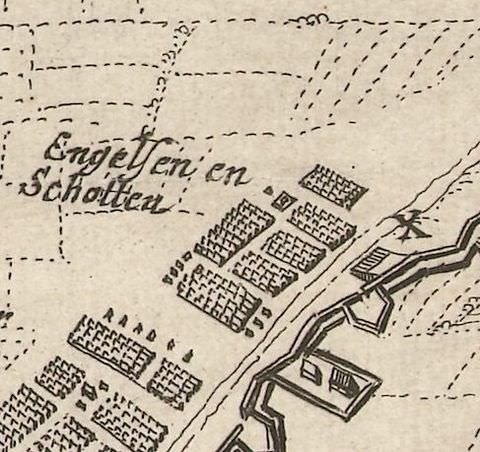

Intense urbanisation and commercialisation became the hallmarks of colonisation. The best example of this was when, after 1610, James obliged the City of London to develop the town of Derry, renamed Londonderry. The London guilds built the formidable walls and St. Columb’s Cathedral, which are extant and shown clearly in a map by Thomas Philips, and colonised the entire county of Londonderry in an effort to bring capital and economic prosperity to what it perceived to be a commercial backwater (fig. 7).24 This initiative occurred under the auspices of the Irish Society, a joint-stock company modelled on the 1600 charter of the East India Company; the membership of the Irish Society overlapped with that of the company for much of the seventeenth century.

24

Interestingly, contemporaries compared the economic exploitation of Ireland with that of India: “Ireland is another India for the English, a more profitable India for them than ever the Indies were to the Spaniards”.25 Later, during the 1670s, Gerald Aungier, who was of Irish planter stock, commercialised and colonised Bombay on behalf of the East India Company, much as his grandparents had colonised Jacobean Ireland. Bombay was the Derry of India, a colonial port founded to secure English interests and profits, and within striking distance of the Mughal Empire.

25Response by

-

David A. H. B. TaylorIndependent art historian, curator, and writer

Reproducing James VI and I as “Monarch of the British Isles”

When we consider how successfully or unsuccessfully James VI and I navigated the branding and realisation of the union, we can look to printed portraits of him after 1603 to understand some of the messaging. In those early years, when Scotland was getting used to the departure of its monarch and England to the arrival of a new, foreign monarch, James’s reproduction in print offered a stage for the representation of nationhood, sovereignty, and the king’s multinational inheritance.

When James succeeded Elizabeth I and his image needed to be better known, there was no established English iconography to draw on, so a Scottish painted portrait of the king was reproduced in printed form, which became one of the first depictions of him produced south of the border (fig. 8). This allowed his physical likeness to be seen by a new and broader audience across society in James’s kingdoms, as well as on the continent, and enabled messages concerning politics, religion and nationality to be spread persuasively and cheaply.

The first image of the new British king, dated 1603, which included his recently inherited titles as king of England and Ireland (in addition to Scotland), was based on a painted portrait of him as king of Scots, by his last official portraitist in Scotland, Adrian Vanson, a Protestant Dutchman. It was then engraved by Pieter de Jode I in 1603, along with a pendant of Anna of Denmark. Vanson travelled to England with the court in 1603, the year the engraving was made, although the print shows James with the tall hat and smaller beard that he stopped wearing before he inherited the English throne. The Latin inscription on the print states, in translation, James was “a king elected with great applause”, reminding the viewer that his succession was a choice and not just a right. This importantly highlights that James had acceded to the throne with his new subjects’ consent, emphasising both the desire for and the legitimacy of his kingship.

The next year Crispijn de Passe the Elder engraved an image of James, copying that by Pieter de Jode and thus after the same Vanson portrait. Below the originally Scottish image of the king the Latin inscription (in translation) reiterates that “he holds three kingdoms, living so happily under the King of the Britons”.26 The inscription on a paired engraving of Anna, also after Vanson, describes her old and new British regnal positions metaphorically as “then the scepter of the Scots, now also the diadem of the English”.27 While emphasising James’s native kingdom and previous life, these prints also reveal the complexities of visualising his sovereignty of the whole of the British Isles.

26

James’s right to rule all of Britain was illustrated through engraved genealogies accompanied by explanatory texts—an easily disseminated platform for sharing rhetorical concepts of the legitimacy of union. One such printed broadside, James I, Monarch of the British Isles, engraved by Nicolaes de Bruyn and published by Jean le Clerc in 1604, again shows the complexities of visualising the union (fig. 9).28 James and Anna are shown full length, crowned and robed, and standing before mountainous landscapes that presumably represent Scotland. A family tree between them, beginning with Henry VII and Elizabeth of York and finishing with Henry, Prince of Wales, has an explanatory text below describing “the genealogy of James VI, King of Scotland, and by what right he came to the Kingdoms of England and Ireland”. Some confusion around titles and countries reveals an Anglocentricity to the production and intended consumption of the image; a roundel describes the future Charles I as Prince of Rothesay, a title he didn’t gain until after his brother’s death, eight years after the broadside was published, and the king’s Latin titles have him as monarch of England and Ireland, with Scotland added above via a caret, as though it were an afterthought.

28Printed images of James and his family that included genealogies reiterated the king’s Scottish heritage and legitimacy within the framework of an English royal bloodline. This was emphasised in 1604 when James, to some extent still an unknown quantity for many of his new subjects, declared that the union was “made in my blood”. Both James’s parents united Scottish and English royal bloodlines, and genealogical engravings straightforwardly explained his pedigree and right to succeed in England.29

29Another image, engraved by Jan Wierix in the first decade of the king’s English reign, mixes ideas of nationhood, religion, and empire. Based on earlier Scottish portraits, it shows James and Anna at full length before another mountainous, presumably Scottish, landscape.30 The design was repeated by a now anonymous engraver soon after, including an inscription calling on James to “protect the faith, so Babylon may now fall” and describing Anna as “dear to the Britons”.31 The idea of linking nationality with the physical landscape allowed London-centric racial-political perceptions of Scotland’s otherness to present an imagined, sparsely populated wilderness, signified by mountains and rocky outcrops.

30Another visual presentation of Britain and imperial kingship, John Speed’s 1611 atlas The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, linked post-1603 James visually with Scotland by including engraved portraits of the king and queen and their sons flanking the only map of Scotland in the volume (despite various maps of England, Ireland, and Wales).32 Ironically, the visual linking of the Stuarts and Scotland contrasts with their portraits’ inscriptions in the engraving, which give preference to their regnal titles in “Great Britain, France and Ireland”, with only the figure of the future Charles I, as duke of York and Albany, referencing his native land. So, while James is described in the text as “inlarger and uniter of the British Empire”, the book ultimately served to emphasise the separate parts of this new empire.

32Therefore engravings that presented James’s multiple kingships visually, ironically, articulated both union and separateness. Within a larger programme of presenting the union, print culture offered a hybridised world that, through the printed reproduction of Scottish portraits, landscapes, and genealogies, reminded English viewers that their monarch was a Scot, at the same time as offering Scottish viewers a sense of the absent James’s presence. As part of the persuasive display of the king’s imperium, this materialising of union for new audiences could at least offer some sort of lasting version of James’s Great Britain.

Response by

-

Clare JacksonHonorary Professor of Early Modern History and Walter Grant Scott Fellow in HistoryTrinity Hall, University of Cambridge

A Tale of Two Treaties

Anna Groundwater has rightly restored historians’ attention to the rich visual and material culture of James VI and I’s court. While the king’s notable hat jewel, known as the “Mirror of Great Britain”, offers a spangling, symbolic endorsement of his vision of a united Britain, mirrors also supplied James with one of his favourite verbal images and featured frequently in his parliamentary speeches, proclamations, published tracts, and private letters. In March 1610, for example, he opened a speech to the Westminster Parliament by offering English peers and members of parliament “a great and a rare present, which is a fair and a crystal mirror … as through the transparentness thereof, you may see the heart of your king”.33 Yet, while mirrors reflect present realities, they also have the capacity to distort and deceive. Accordingly, my own reflection on James’s life and kingship—published earlier this year—was entitled The Mirror of Great Britain to emphasise the multitudinous and shifting dimensions of this most fascinating and complex of monarchs.34

33As Groundwater’s provocation illustrates, James promoted his vision of a united Great Britain via visual and material media, including a new royal title, a redesigned royal coat of arms, a new “Union Jack” flag, and new common coinage introduced into England and Scotland in 1604. Former English “sovereign” coins were renamed “unites”, and bore a Latin legend from the book of Ezekiel that promised “Faciamus eos in gentem unam” (Let us make ourselves into one people), while a text from St. Matthew’s Gospel, “Quae Deux Coniunxit Nemo Separet” (What God has joined together, let no man separate), appeared on silver shillings. Larger silver coins presented British union as Stuart dynastic destiny with the non-scriptural legend “Henricus Rosas Regina Jacobus” (As Henry the roses, so James the kingdoms).35 Descended from the marriage in 1503 of “the thistle and the rose”—his great-grandfather James IV of Scotland and Margaret Tudor—James was now uniting England and Scotland just as his English great-grandfather, Henry VII, had ended the Wars of the Roses by uniting the houses of York and Lancaster in marriage.

35But is Groundwater correct in characterising James’s endorsement of British union a “misleading materialisation”? Certainly, James seemingly assumed that its advantages were so self-evident that they would be universally embraced. He did not, however, accede to Elizabeth I’s throne in 1603 with a precise blueprint for its realisation. Rather, he restricted his role to promoting a royal rhetoric of union, leaving bilateral sets of commissioners, appointed by the English and Scottish parliaments, to work through the detailed practicalities. From his first Westminster parliament, James sought approval only of the appointment of English commissioners, as well as a change in his royal style to “King of Great Britain” from “King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland”; the inclusion of France was pretty redundant by 1603. He left the English commissioners’ remit to peers and members of parliament to decide—they were “to be your own cooks, to dress it as ye list”.36

36Accordingly, in the autumn of 1604, forty English and twenty-eight Scots commissioners met at Westminster and, over six weeks of bilateral negotiations, reached sufficient agreement for their conclusions to be drawn up in the form of an “instrument”, or treaty, between the two parliaments, which was signed by the commissioners on 6 December 1604. The treaty’s recommendations were modest, limited to abolition of mutually hostile laws between England and Scotland, the elimination of certain trade barriers, and the mutual naturalisation of subjects in both countries. For centuries, only one of three original vellum versions of this “instrument” was thought to exist, bereft of its original seals and preserved in the General Register House in Edinburgh. In 1949, however, another copy, preserved at Ham House in Surrey, was transferred to the National Archives, still bearing over sixty red wax English and Scots seals on silk and gold laces (fig. 10).37

37

At Westminster, discussion of this treaty was scheduled for the next parliamentary session, due to open in November 1605. But, in the event, “James’s decision to open the new session in person in order to deliver to Parliament the Instrument of the Union almost cost him his life”—preserved only by the last-minute discovery of Guy Fawkes, and thirty-six barrels of gunpowder, concealed in a cellar beneath the House of Lords.38 In what might be retold as “a tale of two treaties”, it had been another treaty, recently concluded during the summer of 1604—the Anglo-Spanish Treaty of London—that had driven the Gunpowder plotters’ determination to blow up not only James and his two young sons but also the majority of the English political establishment. Signed by James solely in his capacity as king of England, the Treaty of London had radically reoriented English foreign policy and reduced the likelihood of clandestine Spanish support for Catholics in the British Isles. As The Somerset House Conference vividly recorded for posterity, it was also one of the first major peace treaties between warring Protestant and Catholic states in the post-Reformation era (fig. 11).

38

Discovery of the Gunpowder Plot prompted the English Parliament’s immediate prorogation. By the time the other treaty of 1604—the “instrument” of Anglo-Scottish union—was debated at Westminster over the winter of 1606–7, domestic priorities had shifted. More broadly, discussions of Scottish sovereignty had rehabilitated historic claims of English suzerainty over Scotland; calls for freedom of trade had resurrected stereotypes of Scots indigence; ideas of ecclesiastical conformity had reignited fears of Puritan resurgence; and plans for Anglo-Scottish legal union had raised common lawyers’ hackles and deepened divisions between rival common law and equity jurisdictions. Accordingly, by the time James addressed the English Parliament in March 1607, he was dismayed to observe “many crossings, long disputations, strange questions and nothing done”. His initial hopes for unus Rex, unus Grex et una lex—one king, one people, and one law—had failed to gain traction. His confidence had been misplaced; as he later conceded, “I knew my own end, but not others’ fears”.39 That August, the Scottish Parliament adopted the Instrument’s recommendations and passed an “Act anent the union of Scotland and England” that would become effective only when the English Parliament passed parallel legislation. That eventuality did not come to pass, but James’s materialisation of Anglo-Scottish union was not misleading in the sense of being deceptive. It was, rather, a logical desire to convert the advantages of dynastic succession into territorial consolidation and an energetically creative attempt to endow ideas of Britishness with tangible psychological, visual, and material heft.

39Response by

-

Steve MurdochProfessor and Head of DepartmentThe Swedish Defence University

Visualising Britishness

As Anna Groundwater has insightfully reminded us, the public reaction to and reception of the composite monarchy in Britain and Ireland unfolded unevenly across the kingdoms. The hat jewel known as the “Mirror of Great Britain” is undoubtedly one of the better-known embodiments of the very idea of a united Great Britain, but it is far from the only reflection of the idea. It did not take long for the concept of Britain to make its appearance across several spheres, including the written word, and also in physical manifestations of Britishness. As can be seen in the 1607 inscription of the hunting lodge that stands opposite the royal Stuart palace of Falkland, the king could well be described as King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, but he remained the long-reigning Scottish monarch James VI rather than the new-fangled James I—a title that many felt refocused the start of the king’s reign in 1603 away from its actual beginning in 1567 (fig. 12). Alas, to many scholars past and present, this foreshortened reign ignores many aspects of James’s kingship including his frequent outings as a military commander, his diplomatic ties to northern Europe (cemented by personal trips to Norway, Sweden, and Denmark), and his work as a theologian of some repute.

As the Falkland inscription shows us, the concept of Great Britain—regardless of the English Parliament’s rejection of the “Perfect Union” of Scotland and England—was adopted particularly, though not exclusively, by James’s Scottish subjects. Indeed, a new British supra-identity found expression when individuals self-identified using terms such as Scotto-Britannus, Anglo-Britannus, and Cambro-Britannus.40 It is unlikely that this hybridisation of national and supra-national identities is what James had envisioned when he proclaimed himself king of Great Britain, France, and Ireland in October 1604. Nevertheless, adherence to Britishness could also be visualised and presented in several ways, particularly in spheres where the king reserved authority to himself. Specifically, this included the Stuart diplomatic corps, the Royal Navy, and British expeditionary forces abroad. While the diplomatic corps were co-opted into a Stuart institution by virtue of the royal accreditation with which the diplomats visited foreign potentates,41 the Royal Navy and military expeditions embodied Britishness through their adoption and use of versions of the Stuart Union flag (fig. 13).42

40

For the Royal Navy this “flagging” was formalised in a decree in April 1606 and was something of which Charles I became very protective, reserving the Union flag’s use for his “Navy Royall” in 1634.43 Far less well known was the deployment of combined British expeditionary forces soon after the 1606 proclamation. In 1609 a British army was assembled in the Dutch Republic, drawn from regiments of both the Scots-Dutch and the Anglo-Dutch brigades. While these units were regularly billeted together and fought side by side in the Dutch Republic, they were nevertheless discrete national units (fig. 14).44

43

However, both brigades belonged to the Stuart king and could be recalled or deployed elsewhere as he saw fit. It was under the first of these deployments, the dispute over Juliers and Cleves in 1610, that an early integrated British expeditionary army was formed.45 The opening years of the Thirty Years War also saw a marked increase in public declarations of Britishness, both in broadsheets and in mundane activities such as university matriculation.46

45Foreign potentates continued to engage with the separate parliaments and privy councils of Scotland and England throughout the seventeenth century. However, this coincided with the need to deal directly with the Stuart Crown and its insistence on the recognition and use of the term “Britain” when the Crown saw fit. Thus, we find correspondence from the likes of Gustav II Adolf of Sweden asking his ambassador to ensure that no fleet or single ship might be procured from England, Scotland, or Britain, which can best be understood as being supplied by the English or Scottish estates, or the British Crown (fig. 15).47

47

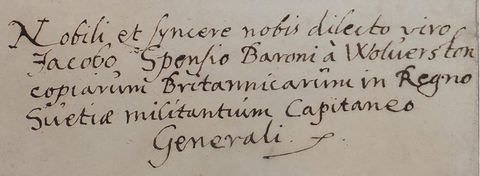

More emphatically, the Swedes formally appointed Sir James Spens of Wormiston “Captain General of the British Forces serving in the Kingdom of Sweden” (fig. 16).48 Spens was the first of three men to hold the title, which became moribund only on the outbreak of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in 1639. But even then, Britishness retained currency among the overseas community. General James King of the Royalist forces, for example, exclaimed to his former military masters in Sweden in 1641: “Briteannia ist mein patria, darin ich geborn sey” (Britain is my fatherland, that is where I was born).49

48

It seems, then, that the concept of Britishness enjoyed more success than scholars of King James usually admit to. Perhaps it is not so surprising that this supra-national identity took greater hold among those individuals bound together in communities beyond the shores of the island itself: diplomats, mariners, and soldiers working with and for their British monarch and fellow Stuart subjects abroad. After all, as many exiles have experienced over time, the further one is from the familiarity of one’s home the greater the affinity one can feel with neighbours of similar outlook. As such, to “visualise Britishness” afforded the Scots, the English, and the Welsh a plausible common identity through which they might more easily cooperate together abroad.

Response by

-

Cameron MacleanDoctoral researcherUniversity of Glasgow

Heraldic Representation

Anna Groundwater’s provocation, through consideration of visual and material culture, highlights both the complexity of representing the Union of the Crowns and Scotland’s repeated attempts to assert its equal status with England. As she writes, this resulted in malleable ‘‘expressions of Britain’’ that catered to ‘‘each realm’s concerns’’. The same pattern can be seen in the development of James VI and I’s royal arms in the years following his accession to the English and Irish thrones.

The royal arms, which were depicted in a wide array of media, including coins, seals, architecture, engravings, and paintings, were a ubiquitous symbol of the king’s authority.50 Representing his kingdoms through heraldry was an immediate concern for James after he assumed his new thrones on 24 March 1603. He had decided on the composition of his royal arms by 13 April 1603 when, while in Newcastle en route to London, he set the designs for his first English coins.51 As exemplified by the gold sovereign, those arms represent the monarch’s three kingdoms and claim to the kingdom of France in a shield divided into quarters (fig. 17). The leopards of England and fleur-de-lis of France appear in the first and fourth quarters, the lion rampant of Scotland in the second, and the harp of Ireland in the third. This heraldic placement—here I will refer to it as the English-style arms—afforded precedence to England and France, and occurred on all of James’s English coins and seals that depicted the royal arms.52

50

It was not until 1605 that a version of the royal arms that gave precedence to Scotland was authorised by the king. These arms—the Scottish-style arms—first appeared on James’s post-union Great Seal of Scotland (fig. 18). The king ordered the creation of this new Scottish Great Seal on 11 February 1605, and the engraver of the Scottish Mint was tasked with making its matrices on 28 March 1605.53 Until they were delivered, the pre-union Great Seal of Scotland, which depicts the Scottish lion rampant alone, remained in use. The heraldic arrangement on the new Great Seal retains the components of the English-style arms, but precedence is granted to Scotland by transposing the position of the Scottish arms with those of England and France. The practice of maintaining separate arms, one for use in Scotland and another for the rest of the British Isles, was a suitable compromise, as the two kingdoms could not be represented equally on a single coat of arms.

53

It is evident that, at least initially, the English-style arms were considered acceptable in Scotland, as they were used before the institution of the new Great Seal. This is reflected on the first Scottish coins to be introduced after James’s English accession. These coins, which are categorised as James’s ninth Scottish coinage, were authorised in November 1604 and entered circulation from February 1605.54 Usage of the English-style arms prior to the creation of the seal is further evidenced by the silver seal case, commissioned by John Graham, earl of Montrose, to house the pre-union Great Seal of Scotland attached to a royal commission of 13 December 1604. This document appointed Montrose as great commissioner of Scotland.55 With the probable intention of representing his benefactor’s recently elevated status and enhancing his own by association, Montrose had the seal case adorned with a version of the royal arms that symbolised James’s role as monarch of multiple kingdoms rather than, as the pre-union Great Seal appended to the commission indicated, king of Scots alone. As the Scottish-style arms had yet to be devised, the English arrangement was depicted. The new Great Seal served as the progeniture of the Scottish-style arms. It was not until after its creation that the arms began to appear in other media, with an early example being the fireplace at Huntly Castle, which dates to 1606.56

54Even after their introduction, it would be a further four years before the Scottish-style arms proliferated more broadly in Scotland. Coins struck at the Scottish Mint continued to depict the English-style arms until 1609. On 10 November of that year, James ordered that the arms be changed on the coins to match ‘‘the same very forme’’ used on the Great Seal.57 The new coins, categorised as James’s tenth Scottish coinage, were duly introduced and continued to be struck until the king’s death in 1625.58 The placement of the arms on Scottish coins, which were minted in large quantities and circulated widely, significantly increased their visibility. Also in 1609, the Scottish-style arms made their first appearance in publications printed in Scotland when they featured in four books.59 One, a collection of poetry by Alexander Gardyne, may contain an ode to these efforts. In a poem titled ‘‘vpon his majesties Armes quartered’’, Gardyne celebrated the primacy of the Scottish arms over those of the other kingdoms when he wrote: ‘‘The Leopards, and Flowres of France they bring / The Harpe, to sport their Lord, thee Lyon King’’.60 These developments reflected a wider motive in Scotland, which was also manifested in disputes over the composition of the Union flag, to ensure that Scottish symbols were not subservient to their English counterparts in representations of the union.61

57The measures to further disseminate the Scottish-style arms had an impact. The practice of maintaining separate arms for use in Scotland was firmly entrenched by the end of James’s reign. Indeed, it has been followed by all of the king’s successors to the present day.62 However, in spite of this long-standing convention, the extended timeline of the arms’ introduction and spread shows that neither their creation nor their endurance was a foregone conclusion. Instead, the delay reveals the complexity of Scotland’s attempts to represent its equal status with England, as, at least initially, use of the English-style arms was deemed acceptable. The compromise of maintaining separate arms also showcases the flexibility of visualisations of the union depending on the kingdom for which they were intended.

62Response by

-

John PeacockVisiting Fellow in EnglishUniversity of Southampton

Inigo Jones and the Jacobean Dual Monarchy

In considering the means by which the Union of the Crowns under James VI and I was symbolised in material terms, it may seem implausible to associate a jewel, however fraught with meaning and charismatically displayed, with the spectacular and diffuse magnitude of the court festivals that were also used to characterise the rule of the first king of “Great Britain”. But the Stuart court masques, inaugurated by James’s consort, Anna of Denmark, and taken up (before death intervened) by their son Prince Henry, proved to be the most pervasive material figurations of the king’s desire for a closer rapprochement between the English and Scottish polities. Although the idea of the masques as substantive instruments of political symbolism was initially disputed, it became established under the leading practitioners of the form, the poet Ben Jonson and the stage designer and producer Inigo Jones. While Jonson, as publisher of the texts, became the spokesman and advocate of the masques as “solid” vehicles of Jacobean ideology, he was (in this early, cooperative phase of their relationship) seconded by Jones in ways that have not received due attention.

Although the Jacobean masque as a genre—and not just a literary genre but what was later to be called a Gesamtkunstwerk—came to be defined by the pronouncements of Jonson, the initial masque of the reign had a text by Samuel Daniel. This was The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses (1604), in which Queen Anna represented Pallas, personifying militant wisdom.63 Its themes, to be reiterated in succeeding masques, were the “blessings” of James’s rule, such as “England and Scotland joined”, symbolised by the goddess Concordia, and the new imperium of the joint monarchies, “mighty Britany”, with the procession of deities headed by Juno “the Goddess of empire and regnorum praesidii” (of protection of kingdoms).64 However, these motifs, taken up and repeated soon after in the masque texts of Jonson, complemented by Jones’s designs, were associated by Daniel with a theory of the masque that Jonson found antipathetic. Here (and he sharpened the point in the text of his later masque Tethys’ Festival65), Daniel expounded a view of the form as (to quote his former title) a “vision”,66 an imaginative spectacle that was wondrous but passing. Shakespeare famously characterises this view by having Prospero describe his masque performed by spirits in The Tempest as an “insubstantial pageant”, a feat of short-lived magic. Scenarios highlighting the queen and her ladies may not have boosted the king’s aim of an enduring political union when allied to a view of the masque as an ephemeral “vision”. For Ben Jonson in collaboration with Inigo Jones this notion was quite inadequate.

63Drummond of Hawthornden reported Jonson as boasting that “next himself only Fletcher and Chapman could make a masque”.67 Although the reference to Fletcher may be a slip for his writing partner, Beaumont, the point here is that a masque is something “made”, a substantive artefact. The early Haddington Masque (1608), celebrating the marriage of an English earl’s daughter to a Scots nobleman, in line with the king’s policy of union, introduces the figure of Vulcan, the archetypal exponent of “great mastery or excellent art”, while his two assistants “beat a time … with their hammers” to the dances of the principal masquers.68 Revealing that these two craftsmen were impersonated by Thomas Giles and Jerome Herne, the court dancing masters who had choreographed or “made” (the word used in the text) the dances to which they beat time, Jonson describes a telling episode that intrinsically represents masque artistry as a process of making, a mode of constructive action that reinforces initiatives in the sphere of diplomacy and politics.69

67His chief collaborator Inigo Jones tended to follow Jonson along this path, as far as we can tell from the incomplete but wide-ranging body of surviving visual documentation that parallels Jonson’s textual corpus. A helpful starting point is Jonson’s manifesto preface to his first published masque text, Hymenaei (1606), where he desiderates “not only … riches, and magnificence in the outward celebration or show … but … the most high and hearty inventions, to furnish the inward parts: (and those grounded upon antiquity, and solid learnings)”.70 Even though this argument was to categorise Jones’s contribution as the “outward” or “bodily part”, Jones in his design practice, not only in architecture but also scenography, was equally devoted to “antiquity”.71 For Jones, the visual legacy of the ancients was mediated by the revival of antiquity progressively expatiated in Renaissance classicism, just as for Jonson, schooled in Latin and Greek, the literature of antiquity on which he drew for the masques was often accessed through modern humanist compilations. The attitudes of both chimed with James’s recourse to classical antiquity in his treatise on the “craft” of kingship, Basilicon Doron: its conclusion, with definitive emphasis, quotes the Virgilian prophecy (Aeneid 6.847–53) of Rome’s mission to exercise its civilising imperium.72

70There are traces in the early masque texts, as published by Jonson, of attempts by Jones to signal that his contribution to glorifying the Jacobean monarchy and its aim of political integration was “grounded upon antiquity”. In Hymenaei, designated by D. J. Gordon the “masque of union”,73 we read that the male masquers’ costume “had part of it, for the fashion, taken from the antique Greek statue, mixed with some modern additions”.74 No drawing of this design survives, although for the later Lords’ Masque (1613) we do have a design for a “Fiery Spirit”, a composite image of two figures of antique sculpture, as recorded in sixteenth-century prints, one of them the Apollo Belvedere.75 Thomas Campion, who wrote this masque, and Daniel in Tethys’ Festival, allow generous space to describe Jones’s work as designer, explicitly using descriptive details that he has supplied.

73The latter of these was presented by the queen to celebrate the investiture of Henry as Prince of Wales and Great Britain (the title significantly augmented), and the enlarged imperium to which he was now recognised as heir evoked Virgilian allusions to the imperial Rome of Augustus; a design by Jones for the headdress of the queen, who represented Tethys, was adapted from a Titianesque print of Livia, Augustus’s consort.76 This was the symbolic milieu in which Jones’s designs, “grounded upon antiquity”, made their contribution to James’s effort to see “nations joined” (a newly charged motif from the year of Henry’s investiture). Another design for Tethys’ Festival, the image of an attendant Naiad, paraphrases an engraved personification of Temperance after Raphael, in a classicising style evocative of antique sculpture.77 There are similar designs for a range of masque figures from the early years of James’s reign that are stylistically akin and are traceable to classicising sources. One, its context now identifiable, is a highly finished design for a lady masquer in pen and ink and watercolour,78 based on an image of Homer’s Circe engraved by Giulio Bonasone after Parmigianino (figs. 19 and 20).79 The adaptation of a late Renaissance classicising figure into a Jacobean masquer, “taken from the antique … with some modern additions”, is contrived with noteworthy graphic and painterly skill, showing at its best Jones’s efforts through his masque designs to enlist the visual vocabulary of classicism in support of the king’s dream of a composite Great British monarchy.

76

Response by

-

Charlie SpraggDoctoral researcher in History of ArtUniversity of Edinburgh

King James VI and I’s “British” Coronation

Advocates of an Anglo-Scottish union often spoke prophetically, particularly before 1603. These writers proclaimed that the two nations were always headed towards the restoration of the (highly mythologised) antique Britain from the era of Roman rule. They had merely been awaiting the birth of a prince who would unite the Scottish and English royal families in his blood. As an infant, King James VI of Scotland was declared the future king of Britons by Scottish writers and, as he matured, he took this to heart.80 James finally secured his long-awaited inheritance of the English throne on 25 March 1603. The crowns of Scotland and England were henceforth to be united. As Anna Groundwater has outlined, James’s mission was to secure a lasting political union between his kingdoms that extended beyond the merely dynastic, forming a single nation under the name of “Britain”. The central event upon the ascension of a monarch was their coronation, which provided a critical indication of the style their reign might take. James’s English coronation was promptly held on 25 July at Westminster Abbey. The event made clear that his was to be a distinctly British monarchy, predestined by the Anglo-Scottish union made manifest in his person.

80A sizeable crowd gathered along the royal procession route from the River Thames to the Abbey, eager to catch a glimpse of their new ruler. James was presented to his audience as the glorious leader of the restored empire of Britain. The sovereign was adorned in a traditional grand velvet robe of imperial red, trimmed with luxurious powdered ermine and finished with gold and pearls. He walked under a canopy of rich cloth of gold finished with silver bells, coloured silks, and gold and silver detailing. Twelve heralds and the king at arms preceded him, each wearing a tabard “displaying the arms of the four kingdoms”, those of England (into which Wales was formally incorporated), Ireland, France, and now Scotland.81 This may have been one of the first uses of James’s integrated royal arms, which, according to Cameron Maclean’s contribution to this feature, had been consolidated by April of that year. Those who accompanied James in the procession bolstered the impression of his imperial authority. Everyone in the royal entourage wore red (aside from the newly made knights of the Order of the Bath). The broader theme of unity was frequently invoked in encomia and pageantry in support of the king and his British vision. Here, the entire procession was chromatically united around James.

81

This overall image of Britannic imperium was immortalised through official commemorative coronation medals, which were presumably distributed to the crowds and guests (fig. 21).82 The king was depicted in the style of a Roman emperor in laureate bust, encircled by the inscription “James I, Caesar Augustus of Britain, Caesar the heir of the Caesars”, and on the reverse “Behold the beacon and safety of the people”. Through image and text, these tokens explicitly established James’s intention to unite his domains as one nation under the name of Great Britain, and their very physicality reinforced his resolve. These medals were an innovative tool; none had been made for the inauguration of any previous English or Scottish monarchs. Gifted to their owners, the medals encouraged a personal connection to the idea of themselves as British as they handled their novel possession, both during the festivities and as time passed.

82The sense of prophetic promise was bolstered in the inauguration ceremony. Following the anointing, James sat on the throne of St. Edward the Confessor to receive the ancient vestural relics of the realm. Within the base of the seat was placed the Stone of Destiny (fig. 22).83 The stone had originally played a central part in the Scottish coronation ceremony, stemming back to the ritual of Dalriada, before it was seized and taken to England in 1296 by Edward I of England during the Wars of Scottish Independence. By 1603, the stone had become an integral part of the English royal regalia. For it to be reunited for the first time in 300 years with a king of Scots was undeniably significant. This ceremony saw the fulfilment of an enduring medieval Scottish oracular verse, most likely written after the stone’s capture, which foretold that Scotland would establish rule wherever it should rest.84 To be the first king of both Scotland and England to use the collective inaugural regalia vindicated James’s claim to be the “Caesar Augustus of Britain”. Cloths of estate—tapestries that hung behind the throne—embroidered with the “Armes of his Ma[jesties] Kingdomes as they are now quartered” called further attention to the gravity of this moment.85

83

However, the presence of the stone at the Abbey could also be considered disadvantageous to James’s promotion of a “perfect” union of equal partners. Edward I had taken the stone forcibly as part of his campaign to impose English influence over the British Isles. Displacing and claiming ownership of the relic was a means of undermining Scottish national sovereignty.86 The stone on which the self-styled British king sat evoked the long history of Anglo-Scottish hostilities and spoke of a moment of Scottish subjugation to English authority. That this could become their reality was of genuine concern for Scots in 1603. Conversely, many English feared the Scottish dominion that its prophetic verses predicted.87

86At his 1603 coronation, King James readily took up the mantle of the foretold British emperor, sumptuously arrayed and accompanied by heralds bearing the arms of all his kingdoms and a unified red retinue. Those who received a commemorative medal for the occasion would keep the new royal persona immortalised. James’s self-identification as a British king was not greeted with enthusiasm when he met with his English Parliament for the first time the following year. The members refused outright to support his request to change the royal title. Nevertheless, under his prerogative, James continued to fashion himself as king of Great Britain.88 The reunion of the Stone of Destiny with a king of Scots for his English inauguration may initially have appeared prophetic of the advent of a great union. Ultimately, anxieties and contentions over the impact this could have on either nation, such as those surrounding the stone, would mark the rest of James’s reign. The overarching fear of an unequal and unhappy partnership between the Scots and the English became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

88About the authors

-

Anna Groundwater is Principal Curator, Renaissance and Early Modern History at National Museums Scotland.

-

Catriona Murray is Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. She is a specialist in the art, objects, and performances of the Tudor and Stuart courts and has published widely on topics from seventeenth-century print culture to nineteenth-century historiography. Her first book, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity (Routledge, 2016), explored the strategic promotion of royal familial imagery as a compelling but ultimately precarious art of political communication. She is currently completing her second book, which considers the Stuart dynasty’s involved relationship with statuary and monuments, analysing how sculpture served to mediate royal authority, public loyalty, and political opposition.

Footnotes

-

1

J. H. Elliott, “A Europe of Composite Monarchies”, Past & Present 137, no. 1 (1992): 48–71, DOI:10.1093/past/137.1.48; John Nicholls, The Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, vol. 2 (London, 1828), 46–47. ↩︎

-

2

Ancient and mythologised understandings of a Britain had existed for hundreds of years, underpinned by the territorial integrity of mainland Britain, but it remained conceptual until the uniting of the thrones of England and Scotland in 1603. The term “King of Great Britain, France, and Ireland” (Magnae Britanniae, Franciae et Hiberniae Rex), which also included historical claims to France, was included on coinage from then on. ↩︎

-

3

Roy Strong, “Three Royal Jewels: The Three Brothers, the Mirror of Great Britain and the Feather”, Burlington Magazine 108 (1966): 350–53. ↩︎

-

4

Recent historical fiction includes compelling books by Jenni Fagan, Hex (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2022), and by Naomi Kelsey, The Burnings (Manchester: HarperNorth, 2024). ↩︎

-

5

Thanks to the work of Jenny Wormald, Stephen Reid, Julian Goodare, Susan Doran, Pauline Croft, Michael Questier, and others and to a current group of adventurous doctoral students. ↩︎

-

6

Jenny Wormald, “King James VI and I: Two Kings or One?”, History 68, no. 223 (1983): 187–209. See also, more recently, Michael Questier, “The Reputation of James VI and I Revisited”, Journal of British Studies 61 (2022): 949–69. ↩︎

-

7

The Jacobean Union: Six Tracts of 1604, ed. Bruce R. Galloway and Brian P. Levack (Edinburgh: Scottish History Society, 1985), ix; Speeches to Parliament, 31 March 1607 and 19 March 1604, in King James VI and I: Political Writings, ed. Johann P. Sommerville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 137, 161–63, 168. ↩︎

-

8

Speech to Parliament, 19 March 1604, in King James VI and I: Political Writings, 135. ↩︎

-

9

“The Italians Pegme”, in Stephen Harrison, Arches of Triumph (London: John Sudbury and George Humble, 1604), British Museum, 1906,0719.11.4. ↩︎

-

10

For the wider conversation, see Nicholas Canny, “Irish, Scottish and Welsh Responses to Centralization, c.1530–c.1640: A Comparative Perspective”, in Uniting the Kingdom? The Making of British History, ed. Alexander Grant and Keith J. Stringer (London: Routledge, 1995), 147–69. ↩︎

-

11

See further Lorna Hutson, England’s Insular Imagining: The Elizabethan Erasure of Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023). ↩︎

-

12

Merchant Taylors’ Company Wardens’ Accounts, 1603–4, London Metropolitan Archives, CLC/L/MD/D/003/MS34048/008, fol. 257r. ↩︎

-

13

Thomas Dekker, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment (London: T[homas] C[reede] for Tho. Man the yonger, 1604), A4v–B1r. ↩︎

-

14

Dekker, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment, B2v. ↩︎

-

15

Dekker, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment, A4v. ↩︎

-

16

Dekker, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment, C2v. ↩︎

-

17

Dekker, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment, C4r–v. ↩︎

-

18

Stephen Harrison, Arch’s of Triumph (London: John Windet, 1604), F1r. ↩︎

-

19

Dekker, The Whole Magnificent Entertainment, F1v. ↩︎

-

20

Jane Ohlmeyer, Making Empire: Ireland, Imperialism and the Early Modern World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 1–67. ↩︎

-

21

Breandán Ó Buachalla, “James Our True King: The Ideology of Irish Royalism in the Seventeenth Century”, in Political Thought in Ireland Since the Seventeenth Century, ed. D. George Boyce, Robert Eccleshall, and Vincent Geoghegan (London: Routledge, 1994), 7–30. ↩︎

-

22

Eoghan Ruadh Mac an Bhaird, quoted in Ó Buachalla, “James Our True King”, 10. ↩︎

-

23

Ó Buachalla, “James Our True King”, 14. ↩︎

-

24

John McGurk, Sir Henry Docwra, 1564–1631: Derry’s Second Founder (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2006). ↩︎

-

25

John Lynch, Cambrensis Eversus, vol. 3, trans. Matthew Kelly (Dublin: Celtic Society, 1851–52), 75. ↩︎

-

26

Daniel Francken, L’oeuvre gravé des van de Passe (Paris: Rapilly, 1881), 679.1. ↩︎

-

27

Crispijn de Passe the Elder, Anne of Denmark, 1604, National Portrait Gallery (NPG D25723), https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw128175/Anne-of-Denmark. ↩︎

-

28

F. W. H. Hollstein, Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engraving and Woodcuts 1450–1700, vol. 4 (Amsterdam: Menno Hertzberger, 1950), 274. ↩︎

-

29

See Arthur M. Hind, Engraving in England in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964), 209.96. ↩︎

-

30

Jan Wierix, Iacobus et Anna, Rex et Regina Angliae, Franciae, Scotiae et Hiberniae, 1603–18, British Museum (BM O,8.168), https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_O-8-168; L. Alvin, Catalogue raisonné del’oeuvre des trois frères Jan, Jérome et Antoine Wierix (Brussels: T. J. I. Arnold, 1866), 1956. ↩︎

-

31

Anonymous, Iacobus et Anna, Rex et Regina Angliae, Franciae, Scotiae et Hiberniae, 1603–16, British Museum (BM 1848,0911.270), https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1848-0911-270. ↩︎

-

32

Jadocus Hondius, in John Speed, The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine (London: John Sudbury and George Humble, 1611), Cambridge University Library, Atlas.2.61.1, https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PR-ATLAS-00002-00061-00001/4. ↩︎

-

33

“Speech to Parliament of 21 March 1610”, in James VI and I: Political Writings, ed. Johann P. Sommerville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 179. ↩︎

-

34

Clare Jackson, The Mirror of Great Britain: A Life of James VI & I (London: Penguin Books, 2025). ↩︎

-

35

See B. J. Cook, “‘Stampt with Your Own Image’: The Numismatic Dimension of Two Stuart Successions”, in Stuart Succession Literature: Moments and Transformations, ed. Paulina Kewes and Andrew McRae (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 303–18. ↩︎

-

36

Journal of the House of Commons, vol. 1, 1547–1629 (London, 1802), 193 (21 April 1604), British History Online, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/commons-jrnl/vol1/p193 (quotation modernised). ↩︎

-

37

“One of the three counterparts of the proposed treaty of union of England and Scotland, signed and sealed by the English and Scots parliamentary commissioners”, 6 December 1604, The National Archives, Kew, PRO 30/49/1. ↩︎

-

38

Andrew Thrush, “The Jacobean Union Revisited, 1603–1607”, in James VI and I: Kingship, Government and Religion, ed. Alexander Courtney and Michael Questier (Abingdon: Routledge, 2025), 85. ↩︎

-

39

“Speech to Parliament of 31 March 1607”, in James VI and I: Political Writings, ed. Sommerville, 160. ↩︎

-

40

Steve Murdoch, “Anglo-Scottish Culture Clash: Scottish Identities and Britishness, c.1520–1750”, Cycnos 25, no. 2 (2008): 254–58. More detail on Cambro-Britannus is given in Philip Schwyzer, “The Age of the Cambro-Britons: Hyphenated British Identities in the Seventeenth Century”, Seventeenth Century 33, no. 4 (2018), 427–39. Irish hyphenated identities tended to consist more of Irish plus another ethnic or regional origin such as Anglo-Hibernus, not least because Ireland, despite being a Stuart realm, is a separate island from Britain. ↩︎

-

41

Steve Murdoch, “Scottish Ambassadors and British Diplomacy”, in Scotland and the Thirty Years’ War, 1618–1648, ed. Steve Murdoch (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 27–50. ↩︎

-

42

John Beaumont, The Present State of the Universe (London: Benj. Motte, 1704), Union flag, image table 3; Scottish Union flag, image table 17. ↩︎

-

43

By the King. A Proclamation Appointing the Flags, as well for Our Nauie Royall, as for the Ships of Our Subiects of South and North Britaine (London: Robert Barker, 1634). ↩︎

-

44

For the full image of Hulst see https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/object/Beleg-van-Hulst-1645–39f6f31b86f2732973ddafdfd8d7a8e0. ↩︎

-

45

Steve Murdoch, “James VI and the Formation of a British Military Identity”, in Fighting for Identity: Scottish Military Experiences, 1550–1900, ed. Steve Murdoch and Andrew Mackillop (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 13–14; A. Th. Van Deursen, ed., Resolutiën der Staten-Generaal, nieuw reeks, 1610–1679, eerste deel, 1610–1612 (The Hague: Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis, 1971), 167, no. 919 (3 July 1610), https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/retroapp/service_statengeneraal/1/images/staten-generaalnr-1-gs135_0167.jpg. ↩︎

-

46

Murdoch, “Anglo-Scottish Culture Clash”, 254. See also the broadsheet, Anon., A Most True Relation of the Late Proceedings in Bohemia, Germany and Hungaria, Dated the 1 and 10 and 13 of July This Present Yeere 1620 (Dort: W. Jones, 1620), 10. ↩︎

-

47

Gustav II Adolf to Sir James Spens, Kopparberg, 21/31March 1627, Riksarkivet, Stockholm, Diplomatica Anglica, I/2/4 (1606–1629), fol. 44. ↩︎

-

48

Letter from Duke Johan of Östergötland to Sir James Spens, Vadstena, 13 September 1611, Riksarkivet, Stockholm, Diplomatica Anglica, 1/5, unfoliated. ↩︎

-

49

Murdoch, “James VI and the Formation of a British Military Identity”, 5. The quote is taken from Letter from Lt. General James King to Axel Oxenstierna, circa July 1641, Riksarkivet, Stockholm, Oxenstiernska samlingen, E.636, James King (Lord Eythin), unfoliated. ↩︎

-

50

Charles John Burnett, ‘‘The Officers of Arms and Heraldic Art under King James Sixth & First 1567–1625’’ (MLitt thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1991). Burnett’s thesis includes an extensive catalogue of depictions of the Scottish royal arms from the reign of James VI and I. ↩︎

-

51

William Henry Black, A Descriptive, Analytical, and Critical Catalogue of the Manuscripts Bequeathed unto the University of Oxford by Elias Ashmole, Esq., M.D., F.R.S., Windsor Herald, Also of Some Additional MSS. Contributed by Kingsley, Lhuyd, Borlase, and Others (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1845), 1453; King James VI and I to the English Privy Council, 13 April 1603, Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Ashmole 1729, fol. 78r. ↩︎

-

52

This term has been adopted for ease of reference. It is admittedly a misnomer, as the arms’ usage was not confined to England. ↩︎

-

53

David Masson, ed., The Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 7, A.D. 1604–1607 (Edinburgh: HM General Register House, 1885), 27, 464–65. ↩︎

-

54

R. W. Cochran-Patrick, Records of the Coinage of Scotland: From the Earliest Period to the Union, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1876), 210–15, 217, 277–84; J. D. Bateson, Coinage in Scotland (London: Spink & Son, 1997), 124. ↩︎

-

55

Ian Finlay, ‘‘The Silver Seal-Case of the Earl of Montrose’’, Burlington Magazine 101, no. 680 (1959): 404–7. ↩︎

-

56

Thomas Innes, ‘‘Heraldic Decoration on the Castles of Huntly and Balvenie’’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 69 (1935): 392–94. ↩︎

-

57

David Masson, ed., The Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 8, A.D. 1607–1610 (Edinburgh: HM General Register House, 1887), 605–6. ↩︎

-

58

Bateson, Coinage in Scotland, 125. ↩︎

-

59

‘‘Scottish books 1505–1700 (Aldis updated)—1601–1691’’, National Library of Scotland, https://www.nls.uk/catalogues/scottish-books-1505-1700/main2/#a1601. All seventeenth-century publications are henceforth referenced by their Aldis numbers. Of the eighty-nine extant printed works published in Scotland between 1603 and 1609, all but eight (Aldis nos. 364.5, 370.5, 372, 373, *376.1, 388, 394.6, 404.5) have been consulted. The four books published in 1609 that feature the Scottish-style royal arms are Aldis nos. 409, 411, 416, and 417. ↩︎

-

60

Aldis no. 411, unpaginated. ↩︎

-

61

Bruce Galloway, The Union of England and Scotland, 1603–1608 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1986), 82–83. ↩︎

-

62

William M’Millan, Scottish Symbols Royal National & Ecclesiastical: Their History and Heraldic Significance (Paisley: Alexander Gardner, 1916), 154–59; Charles J. Burnett and Mark D. Dennis, Scotland’s Heraldic Heritage: The Lion Rejoicing (Edinburgh: Stationery Office, 1997), 55, 57. ↩︎

-

63

Samuel Daniel, The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, ed. Joan Rees, in A Book of Masques in Honour of Allardyce Nicoll (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 17–42. ↩︎

-

64

Daniel, The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, 27, line 87; 32, line 259; 26, lines 25–26. ↩︎

-

65

Stephen Orgel and Roy Strong, Inigo Jones: The Theatre of the Stuart Court, 2 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 1.190–201, 196, lines 369–71. ↩︎

-

66

Daniel, The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, 28, line 126: “these apparitions and shows are but as imaginations and dreams”. ↩︎

-

67

Informations to William Drummond of Hawthornden, in The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson, eds. David M. Bevington, Martin Butler, and Ian Donaldson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 5:351–91, 362, line 38. ↩︎

-

68

The Cambridge Jonson, 3:275n16. ↩︎

-

69

The Cambridge Jonson, 3:270, lines 282–84. ↩︎

-

70

The Cambridge Jonson, 3:667, lines 9–12. ↩︎

-

71

The Masque of Blackness, in The Cambridge Jonson, 2:515, lines 56–57. ↩︎

-

72

King James VI, Basilicon Doron (London, 1881), 159 (facsimile of edition published Edinburgh, 1599). ↩︎

-

73

D. J. Gordon, The Renaissance Imagination, ed. Stephen Orgel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 157–84; “Hymenaei: Ben Jonson’s Masque of Union”. ↩︎

-

74

The Cambridge Jonson, 2:686, lines 522–23. ↩︎

-

75

John Peacock, The Stage Designs of Inigo Jones: The European Context (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 128–29. ↩︎

-

76

Peacock, The Stage Designs of Inigo Jones, 294–95. ↩︎

-

77

Peacock, The Stage Designs of Inigo Jones, 126. ↩︎

-

78

Orgel and Strong, Inigo Jones, 1.203, fig. 59; Roy Strong, Festival Designs by Inigo Jones (London: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1967–68), fig. 3. ↩︎

-

79