Prince Henry’s Feast

Prince Henry’s Feast: Anglo-Dutch Relations and European Politics in Early 1610

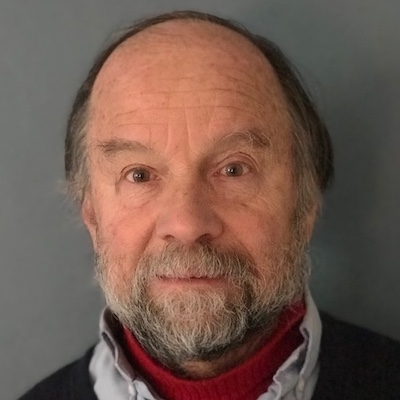

By R. Malcolm Smuts

Abstract

This article presents and analyzes a recently discovered description by the Dutch ambassador Noel de Caron of a feast following a chivalric court entertainment and foot combat in January 1610, known today as Prince Henry’s Barriers. In doing so it seeks to complicate understanding of how this entertainment and the events connected with it conveyed political messages. Previous studies have interpreted the printed text of the entertainment as reflecting opposition between James VI and I’s pacific policies and the staunchly Protestant warlike image projected by his son. By contrast, Caron’s letter allows us to view Henry’s entertainment from the perspective of a contemporary ambassador directly involved in negotiations involving James’s European policies. It highlights the importance of spatial codes and gestures used to signal James’s attitudes toward foreign states, while revealing how he collaborated with Henry to honor the Dutch Republic and to express support for it and disapproval of Spain. The letter therefore helps situate the Barriers in its immediate diplomatic and political context in early 1610, following the conclusion of a truce suspending hostilities between Spain and the Netherlands, and the eruption of a crisis in the Rhineland that threatened to ignite a new European war. The article argues that the political significance of court culture consisted not only in the broadcasting of royal propaganda to the public through visual imagery and theatrical spectacle, but also in how cultural objects and codes shaped relationships within the court, including those with foreign diplomats.

Prince Henry’s Combat Entertainment

Sometime around Christmas 1609, the fifteen-year-old Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, issued a challenge to all comers to fight with him and his companions on foot before a barrier, with lances, pikes, and swords.1 For the next several weeks the court occupied itself preparing “the hall and the equipage for the Prince’s combat”, while Henry practiced his martial skills, wounding a companion as he did so.2 The combat duly took place on 6 January, preceded by an entertainment with speeches by Ben Jonson and scenery by Inigo Jones, in which King Arthur, Merlin, and the Lady of the Lake celebrated the revival of British chivalry. Dressed in crimson velvet adorned with gold lace, and supported by six companions, the young prince fought so strenuously against multiple challengers that by evening he could barely stand.3 The next day the combatants “came all in their liveries very gallantly mounted and in good order from St. James to Whitehall to invite the king and queen to a banquet and a play, which the prince had prepared for their majesties”.4 In all, Henry’s foot combat and associated events cost the exchequer at least £2,986 and the banquet an additional £673.5 These were very substantial sums comparable to the annual income of many peers, although only a fraction of the stupendous cost of the period’s greatest public ceremonies, such as Princess Elizabeth’s wedding in 1613.6

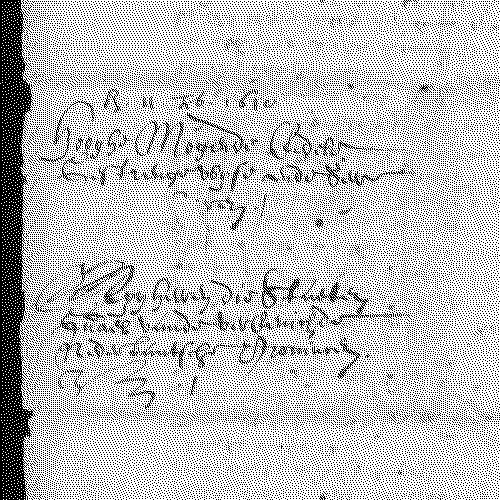

1This article centers on a newly discovered letter by the Dutch ambassador to England, Noel de Caron, that extends our knowledge of this series of events, while complicating understanding of their political significance (fig. 1 and appendix). Previous studies, by Roy Strong in 1987 and by Martin Butler in 2006, situated Henry’s entertainment in the context of public controversy over whether Britain should continue the peace with Spain that James had concluded in 1604, or risk a new military conflict by offering more muscular support to Protestant states on the continent.7 By claiming to revive British chivalry, they argue, the prince symbolically identified himself with “a policy diametrically opposed to the royal one” of good relations with Spain.8 Both accounts, particularly Butler’s, rely on analysis of the printed edition of Jonson’s speeches for the Arthurian entertainment. But, as several scholars have argued, printed entertainment texts, even when supplemented by visual sources such as Jones’s designs for costumes and stage scenery, provide problematic evidence for how contemporaries experienced and interpreted such events.9 We can have no guarantee that such sources are full and accurate, and even if they were, the speeches and images they record usually amounted to only one episode within a longer and more complex spectacle. The political messages recovered by modern scholars through close reading and iconographical analysis may or may not correspond to what contemporaries perceived, and we almost always lack direct evidence of audience responses.

7While Caron’s letter does not solve all these problems, it does open alternative perspectives. It ignores the Arthurian entertainment, which he did not attend, while describing at length the feast hosted by Henry the following evening, which is otherwise sparsely documented. It also undermines the picture of conflict between James and Henry by showing them acting together to honor Caron and the Dutch state. The letter simultaneously offers direct evidence of how one contemporary perceived the significance of Henry’s entertainment in relation to the European political situation of early 1610. Although as a foreigner Caron cannot be regarded as a typical spectator, he was directly involved in negotiations affecting the British Crown’s relations with foreign Protestant states. Seeing events through his eyes therefore shifts attention from the potential public meaning of Henry’s foot combat to British subjects beyond the court, to forms of cultural communication operating within the court itself, including among diplomats. This reminds us that court entertainments operated on multiple levels to address distinct cohorts of spectators and participants, through varied forms of communication requiring complex analysis.

Personal Relationships and Gestural Communication within Court Society

Like any royal court, that of James VI and I was not only a center of ceremony and opulent display but a face-to-face society composed of a restricted number of people who enjoyed various degrees of direct access to the king. Those people generally knew each other personally and often conducted political business not only in formal settings, such as meetings of the privy council and official diplomatic audiences, but also during informal social and recreational activities. The effectiveness of a diplomat like Caron depended in part on his ability to earn the trust and affection of the king and his ministers, but in a court society personal relationships always had a public performative dimension. What mattered was not simply earning the king’s trust and esteem but demonstrating that one had done so, since that would confer both honor and influence. The need to express personal intimacy through visible signs gave rise to systems of gestural communication in which material objects often figured as props, for example in the drinking of toasts, the wearing or doffing of hats, and the presentation of gifts. The intrinsic meaning of an object normally mattered less in these performative acts than the manner of its use in a specific social or ceremonial context. But an object with an intrinsic meaning might sometimes extend and complicate the significance of a gesture, for example when a jewel or painting bearing an iconographic message was presented as a gift.10

10Entertainments performed during the court’s Christmas season involved layers of gestures and representations that conveyed distinct, sometimes related, messages. Henry’s foot combat demonstrated not only his military skills but also his personal attachment to the young nobles and gentlemen he had chosen as his companions, who enjoyed opportunities to deepen their relationship with him through lengthy rehearsals, during which they shared lavish dinners with the prince costing the substantial sum of £100 a day.11 Spectators versed in court politics would have been quick to observe who these companions were and how well they performed their roles as combatants. That would likely have seemed at least as significant politically as the speeches and stage sets of the Arthurian pageant.

11Audience Arrangements, Honor, and the Politics of Space

The configuration of the audience at an entertainment also acquired considerable significance through a “politics of space” that conveyed hierarchical degrees of honor by carefully regulating the placement and movement of people in relation to the king on public occasions.12 The placement of an ambassador’s chair, in greater or lesser proximity to the royal throne, signified the degree of honor to which he and the state he represented were entitled, while a gesture of familiarity, for example if the king turned to engage an ambassador in conversation, would also be interpreted as a mark of honor. Because ambassadors and the kings or republics they represented were extremely sensitive about such matters, audience arrangements easily gave rise to competition and resentment. French and Spanish ambassadors could never be invited to the same entertainment, since neither would yield honorific precedence to the other.13 The English court therefore had to alternate invitations between them. James decided in 1603 to create a new office, the master of ceremonies, to keep track of precedents and negotiate solutions to disputes about invitations, seating arrangements, and related protocols. The post was granted in 1605 to a gentleman pensioner, Lewis Lewknor, who had previously performed its main functions in a less formal capacity.14

12But the king always had the right to waive normal rules of precedence, which never entirely prevented him, or other members of his family, from signaling attitudes toward foreign states by their treatment of ambassadors during public events. At her first English masque in January 1604, Samuel Daniel’s Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, Anna of Denmark scandalized French diplomats not only by inviting the Spanish ambassador as her principal guest, which entitled him to sit beside the king on a raised podium, but also by wearing a scarf and banderole as tokens of her favor to him. She then led him out in a dance at the masque’s conclusion, which he performed “very gaily, like a man of twenty years”, dressed entirely in red, Spain’s heraldic color.15 Her actions amounted to a highly conspicuous gesture of solidarity with Spain some months before the conclusion of the Treaty of London ended England’s war with that country, and not very long after her husband had concluded an agreement with France to lend joint assistance to the Dutch.16 She thereby inserted herself into an ongoing series of sensitive negotiations.

15Unsurprisingly, French representatives at Whitehall strongly disapproved of Anna’s behavior, describing her as an irresponsible figure who threatened to disrupt her husband’s reign.17 But she had probably served James’s purposes by allowing him to signal his sympathy for Spain while simultaneously distancing himself from that signal, as his wife’s action rather than his own. Her conduct also tacitly invited Habsburg diplomats to cultivate her as a source of information and a back channel of access in their negotiations with the English court, which they subsequently did. This enlarged James’s room for maneuver, by allowing Anna to engage in informal discussions of matters such as a potential marriage alliance with Spain that James might then pursue or disavow as occasion served. James also gained an additional way of signaling his displeasure when Habsburg rulers offended him. In late 1606 the ambassador of the archdukes Albert and Isabella, rulers of the southern Netherlands, was told that the queen’s affection for his masters had recently cooled because they refused to hand over the priest Hugh Owen, a chaplain in their Irish regiment, after the English had accused him of involvement in the Gunpowder Plot.18

17The Diplomatic Conjuncture of 1610 and the Problem of Caron’s Status

Caron’s letter shows from its opening paragraph how fully he shared the obsession with outward marks of esteem characteristic of early modern diplomats, by boasting of the “extraordinarily great honor” he had received from the English court, while offering to explain “my conduct and to justify myself” to assure his masters, the States General of the United Provinces, that he had done everything possible to maintain their reputation during the events relating to Henry’s combat. He goes on to explain how his own honor, and that of his country, had been challenged by the Spanish ambassador in London, Pedro de Zúñiga, but were triumphantly vindicated in the end.19 Although Caron does not explain why the Spanish sought to undermine him, two considerations were almost certainly paramount. Henry’s entertainment was the first public performance by an heir to the Crown who was fast approaching the age at which he would begin to develop his own political views and play a more active role in court politics.20 Everyone recognized that Henry would soon provide another indirect channel of access to the king and his ministers even more important than that furnished by his mother because he was expected eventually to become king. The French and the Dutch were especially eager to cultivate him and encourage his martial interests, in hopes that he would promote more vigorous British opposition to the Habsburgs. Caron had already engaged Henry in repeated friendly conversations and presented him with costly gifts from the Dutch States General.21 He would have regarded attendance at the prince’s inaugural court entertainment as an obligatory courtesy. The Spanish may have wanted to prevent his attendance to obstruct his cultivation of the prince.

19But a second consideration weighed even more heavily. Henry’s combat was also the first important English court entertainment after the conclusion of the Twelve Years Truce in April 1609, suspending hostilities between Spain and the United Provinces. The Dutch and their allies, including France and Britain, claimed that by ratifying the truce Philip III had effectively recognized Dutch sovereignty, something that was hotly denied by the Spanish. That dispute bore directly on Caron’s status at the English court. He was already the longest-serving representative of a foreign state at Whitehall, having initially arrived in England in the mid-1580s as a member of a larger delegation, before returning permanently as the chief Dutch agent in 1591. He remained at his post until he died in 1624, by which time he was well into his nineties. Elizabeth had granted him land across the Thames from the court in South Lambeth, on which he built a house surrounded by a fine orchard and a deer park.22 He seems to have been the only foreign diplomat in London to possess his own residence. By 1610 he had been negotiating with some of James’s longest-serving ministers, notably Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury, for nearly twenty years. Until this point, he had not enjoyed the status of an ambassador because Britain, like other European states, had never formally recognized Dutch independence. If the truce had now altered this situation, Caron would become a full ambassador and his treatment during public events would need to reflect this, a prospect Habsburg ambassadors viewed as a public humiliation. They therefore refused to attend any function at which Caron was present and hinted that they might retaliate against his elevation by provoking an altercation.23

22This placed James in an awkward position, because he wanted to avoid antagonizing either the Spanish or the Dutch at a particularly delicate moment in European affairs.24 Despite his professed commitment to peace, he had not wanted the war in the Netherlands to end. It had served his interests by keeping Spain’s army bogged down in a stalemated conflict and the Dutch beholden to him for permitting the recruitment of English and Scottish soldiers to serve in their army. Like other English and many Dutch statesmen, he worried that, once freed from the pressures of war, the United Provinces would suffer crippling divisions over taxation, religion, and other matters, and that their principal leader, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, would drastically reduce the army to save money. To prevent these developments, which would have left his own kingdoms more exposed to attack, he tried to support figures within the Netherlands, especially the commander of the Dutch army, Maurice of Nassau, who opposed large reductions in the military budget and further concessions to Spain. After some hesitation, he also reluctantly agreed to join a triple alliance with the Dutch and Henry IV of France, guaranteeing the terms of the truce. But he did not trust Henry, suspecting him of harboring designs to extend French domination over the Netherlands and of colluding with Spain during the truce negotiations. Rumors had reached him that Henry planned to marry his heir to a Spanish princess, further fanning James’s suspicions and causing him to send signals that he wished to contract his own alliance with Madrid.25 The flight from Ireland of the earls of Tyrone and Tirconnell, the leaders of the great revolt against English rule in the 1590s, made him even more anxious to avoid antagonizing Spain for fear that it might support a new Irish rebellion.

24As all of this was happening, a crisis erupted in the Rhineland after the death of the childless Catholic ruler of the strategically located territories of Jülich and Kleve. The nearest heirs were both Protestants, but the Habsburg emperor Rudolph II talked of sequestering the territories, and one of his brothers, Leopold, levied a small army that seized the town of Jülich. James, along with the Dutch, Henry IV, and a recently formed Protestant Union of smaller German states, all wanted to oppose Habsburg intervention through joint action. However, each proved reluctant to take the lead, hoping to shift the main risks and burdens onto the others.26 James stressed the need to defend the common cause of religion to the Dutch and Germans, hoping to persuade them to act against the Habsburgs while avoiding reliance on Catholic France. To make his pleas creditable, he needed to offer some prospect of British military support, but he also tried desperately to avoid taking a leading role in a major new European war.27

26Against this backdrop, many spectators would likely have perceived Henry’s display of martial prowess as a sign that he wanted a more assertive European policy, as Strong and Butler argue. But this did not necessarily place the prince in opposition to his father, who at this stage was keeping his options open, hoping that the threat of joint action by Protestant powers and France would pressure the Habsburgs into backing down. James may therefore have been happy to let his son hint at a revival of British chivalry as an oblique warning to the Spaniards and an encouragement to his Protestant allies. But a nasty public dispute between the Dutch and Spanish ambassadors in the audience of Henry’s entertainment would have threatened to eclipse and complicate the message of the actual performance, not least by forcing James to favor one party over the other. To head off that embarrassment, several courtiers of middling rank, especially those associated with the Lord Chamberlain, the earl of Pembroke, and the king’s leading minister, Salisbury, were sent to persuade Caron to withdraw his request to attend Henry’s combat. They assured him that if he did so James would find another way to honor him. Caron found these pleas “somewhat strange, for they took from me as much with one hand as they gave with the other”, but ultimately agreed to cooperate.28

28Henry’s Feast

The alternative honor turned out to be an invitation to attend the feast hosted by the prince on the day following the foot combat as principal guest. Caron’s detailed description of this event offers considerable insight into how the consumption of food and drink in a formal court setting provided additional ways of signaling James’s attitude toward European affairs.29 In this period the welcome afforded a guest normally provided the first visible sign of the esteem in which his host held him. Ordinary guests were simply admitted to a house by a servant and allowed to mingle with the company, while those of higher rank were personally greeted by their host at the residence’s door or gate. Especially honored guests would receive an escort that met them before they reached their destination. On his way to Henry’s principal residence of St. James’s Palace, where the feast was to be held, Caron was accordingly met by Sir Lewis Lewknor, three noblemen, and six members of the royal guard carrying torches. The prince greeted him at the entrance to the palace, and after a short interval he received an invitation to join the king in his privy chamber. Since this was a space normally off-limits to everyone except a small cohort of royal intimates and invited guests, the invitation was another gesture of high favor.30 Caron found James attended by Salisbury and his principal Scottish minister, the earl of Dunbar. The king voiced his regret that Caron had not seen the foot combat, and his surprise and disapproval over the conduct of the Spanish. They had failed to instruct their ambassador to initiate relations with him, James complained, although they knew that the English court had accorded him the status of “the ambassador of a free state”. He rejoiced that the Republic of Venice had quickly recognized Dutch sovereignty. The United Provinces should seek all ways to extend and deepen their friendship with Venice, he advised, as “two states, so compatible in their commerce, navigation and all other respects, had many reasons to trust each other”. James continued giving Caron his views on European affairs for nearly an hour, commenting on a dispute over the closing of the Scheldt, which served the port of Antwerp, and the crisis in Kleve and Jülich. He said this particularly threatened the United Provinces but ultimately concerned all Christendom, and that Henry IV was sending him an ambassador to discuss how to handle it. James thus made a show of taking Caron into his confidence, indicating his support for Dutch positions on certain issues while hinting at policy outcomes such as joint action over Kleve and Jülich and an alliance between Venice and the United Provinces that he wanted to promote. The conspicuous marks of honor granted the newly elevated ambassador dovetailed into more substantive, if still informal and seemingly impromptu, efforts at promoting Anglo-Dutch cooperation in ways that were beneficial to the king’s objectives.

29Informed that the feast was ready, James, followed by Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth, led Caron through a throng of nobles “in such great number as I had never seen before, very richly attired and glittering with precious stones, pearls and gold” to a “great gallery”, almost certainly the palace’s newly renovated eastern or cross gallery.31 The sartorial brilliance was another visual demonstration of the British court’s magnificence.32 Anna absented herself, claiming not to feel well. Entering the gallery, Caron saw a table “laid out crosswise, before a throne under a golden canopy, on a raised platform mounted by two steps” and below it, at a distance of about twelve feet, a long table running “the length of the gallery, at which sat 112 people whom his Majesty was able to see” from his raised position.33 These arrangements conformed to traditional dining rituals in great halls while loosely resembling those employed for court masques, where the king also sat on a raised platform that allowed other spectators to watch him as he watched the performance.34

31James seated himself in his chair of state and, in yet another gesture of favor, invited Caron to sit in another chair placed opposite to his own without removing his hat. Henry and Elizabeth sat on either side of the lower table at the end nearer the king, leaving its head open so as not to impede his view. Next came the contestants at the barriers, alternating with countesses; and then earls, barons, and knights, including members of the privy council, seated by rank, again with countesses or ladies alternating with male diners. One guest stood up and drank a toast to the health of the States General of the Netherlands, inviting Caron to respond. He did so by toasting Prince Henry, who replied with a toast of his own. James next removed his hat and drank to the health of Maurice of Nassau, to which Caron responded by toasting the health of the king’s Scottish favorite, the duke of Lennox. Henry then toasted his father. James, evidently failing to hear his son clearly, asked whose health was being pledged. Understanding that it was his own, he stated that he hoped to live to see Henry provide many more such feasts. He then told Caron that he was happy and was sure that the ambassador’s superiors, who were the prince’s godfathers, would also be gratified that he was present at his son’s first banquet. He considered this a good omen.

Toasts were a common feature of early modern feasts, so these exchanges were not particularly surprising, but they also show how toasting could convey both personal and political solidarity between leaders of different states. James’s puzzling description of the States General as Henry’s godparents is particularly interesting. Dutch representatives who attended the prince’s baptism in Scotland in 1594 reported being invited to act as godparents, along with other dignitaries, including Queen Elizabeth. It has never been clear that they actually did so and their role in the baptismal ceremonies has attracted little notice.35 But James, who was fond of invoking his kinship ties to other rulers, obviously believed that they had stood as godparents, thereby creating something of a family tie between his son and the Dutch Republic that gave the alliance between Britain and the United Provinces a quasi-dynastic character.

35At the meal’s conclusion the royal table was removed and replaced by two chairs for James and Caron, who was again instructed to wear his hat. Princess Elizabeth stood to the king’s right, holding three rich jewels, along with Prince Henry, with his head uncovered, the earl of Salisbury, and the captain of the king’s guard and Groom of the Stool, Thomas Erskine, Viscount Fenton. Although the right side of a king was considered more honorable than his left, sitting in his presence while “covered” by a hat was a higher honor than standing “uncovered”. These somewhat ambiguous arrangements appeared to grant Caron honors at least comparable to those of James’s own children. A young man approached the king to inform him of the three contestants who most deserved prizes for their performance during the recent combat. These contestants, each escorted by two ladies, then approached the foot of the dais to receive their prizes from Elizabeth in a ritual with unmistakable chivalric overtones.

By this time, it was past midnight and James excused himself and retired to Whitehall. Henry led Caron and the rest of the company into another room to watch a comedy that lasted nearly another two hours. The ambassador was again seated on a raised dais, along with the prince and princess, while the remainder of the company took their places around the hall. At the comedy’s conclusion Henry led the company back to the gallery, where a table was laid out with sculpted confectionary and marzipan, the “banquet” course that customarily followed a feast. The sweets were shaped into “mills that rotated”, pleasure gardens with fountains of rose water, and cavalry and infantry soldiers that may have been intended to echo the martial themes of the previous day’s spectacle.36 Henry and Elizabeth walked around the table twice, admiring the sugar sculptures and tasting a few of them, before turning away. Immediately the remainder of the company mobbed the table, overturning it as they grabbed at the sweets amid a clatter of shattering crystal. Two other accounts of Jacobean sugar banquets, in 1604 and 1618, describe similar scenes: rushing the table and smashing the king’s crystal was evidently a customary ritual.37

36Caron finally left St. James’s, escorted again by six members of the king’s guard bearing torches and a company of English nobles, who removed their hats in deference to him. He had brought along a company of Dutch dignitaries who crowded into two coaches for the ride back to his residence. Although the Spanish ambassador had declined to attend the feast, protesting that the table would be too crowded, he had sent his secretary and other members of his household to observe, and Caron relished the thought of their having to witness the signs of honor he had received. A few days later a French diplomat reported to his superiors that the Spanish ambassador was, in fact, “surprised and enraged” by what had happened.38 Caron concludes his letter by passing on James’s recommendation that the States General should gratify Viscount Fenton. Although Caron does not say so, the viscount was James’s most intimate servant and head of the royal bedchamber, as well as one of his oldest friends. The king was effectively inviting the Dutch to establish another informal backchannel to him.

38Diplomacy, War, and a Royal Visit to Caron’s House after the Feast

While Anna’s absence from Henry’s feast probably indicated her disapproval, the rest of the royal family therefore acted in unison to signal their approval of the Dutch Republic and disapproval of Spain’s refusal to relinquish its claims to sovereignty over Dutch territory. This did not, of course, guarantee that Britain and the United Provinces would agree to act together in more substantive ways, but over the next several months negotiations over joint action in Jülich and Kleve progressed, culminating in an agreement allowing James to withdraw 4,000 English veterans serving in the Dutch army to serve, under his own pay, as a British contribution to a multinational force intended to expel Habsburg troops from the disputed territories.39 Everyone waited anxiously to see what would happen next.40 “Whereas a year ago men spoke of a general peace”, Dutch representatives in London commented in May, “in the present conjuncture men must think and speak of a general war”.41 They did not yet know that Henry IV, the most powerful participant in their coalition, had been assassinated on 16 May. His murder shocked Europe, leaving James and his Protestant allies dangerously exposed, as French statesmen quickly started scaling back Henry’s mobilization and signaling their intention to limit France’s involvement in European affairs while their new king, Louis XIII, remained a child.42 The prospect that France would cease to act as a counterweight to Spain magnified the risks to Britain of any new European war. But it also made British alliances with other Protestant states more necessary, to avoid the ultimate nightmare of diplomatic and military isolation. James accordingly indicated his willingness to continue a defensive league with the German Protestant Union and reaffirmed his commitment to the preservation of the Dutch state.

39As these events transpired, Caron received another, more informal and seemingly impromptu gesture of royal goodwill. One afternoon in late June, James, Henry, and a company of nobles paid an unannounced visit to his house in South Lambeth, and immediately proceeded to his orchard, where cherries were ripening on the trees. James and Henry climbed the two sides of a double ladder and proceeded to gorge themselves on the fruit for nearly a quarter of an hour, while their noble attendants also picked cherries and playfully assaulted one tree. Caron invited the company inside for a small “banquet”, after which James returned to the orchard and resumed his feasting. Two days later he sent a message asking Caron to provide him with more cherries.43 In early July Anna also visited Caron’s house, unfortunately while he was away on business.44 Caron saw these visits as signal honors, which he attributed to Salisbury’s good offices, for which he was effusively grateful. This suggests that James’s principal minister encouraged him to continue cultivating a closer personal relationship with the United Provinces’ ambassador.

43Conclusions: The Cultural Communication of Political Messages in Early Modern Courts

Since at least the 1960s, most studies emphasizing the political significance of court culture have focused more on communication and propaganda intended for audiences beyond the palace gates than on the internal operation of court societies.45 This perspective, while not erroneous for there is no question that courts did use cultural media to glorify royal conduct, is limiting because it marginalizes the many ways in which texts, material objects, theatrical performances, and ceremonial protocols shaped relationships among the relatively small but extremely influential cohort of people, including diplomats, actively engaged in court life. Happily, some recent studies have begun to redress the balance by looking more closely at the literary and material dimensions of diplomatic practices.46 This article represents a modest further contribution to that enterprise. Caron’s letter points to the complexity of cultural communication within an early modern court, and the need to pay attention not only to texts and representations but also to gestures and spatial arrangements in conveying political messages. It highlights the crucial significance of honor and public reputation in relations not only between people but also between states, while providing the fullest account yet discovered of a major court feast and its associated rituals during James’s reign. Existing studies of Stuart court culture pay scant attention to the consumption of food and drink, no doubt in part because the subject does not lend itself easily to the sort of textual and iconographic analysis in which literary scholars and art historians are trained, which historians interested in political culture have also assimilated.47 But for centuries feasting and ceremonies related to the consumption of food and drink played an absolutely central role in court life, and no study of the court’s material culture can be complete without treating this subject.48

45The perspectives opened up by Caron’s letter do not necessarily invalidate alternative interpretations of Prince Henry’s Barriers, including those of Strong and Butler. But that letter does underline the need to question whether complex court spectacles such as this one can ever have conveyed wholly uniform and unambiguous messages, given the range of people involved as spectators or participants, and the differing vantage points, personal interests, and prejudices that must have affected individual reactions. Although we will never find much direct evidence of how most contemporaries who witnessed a court entertainment or feast interpreted its meaning, we need to recognize that in all probability they would not have done so in entirely consistent ways. While the decoding of entertainment texts and images by modern scholars may help us understand at least some of the intended meaning of court entertainments, it cannot by itself provide a complete explanation of their full contemporary significance. Greater sensitivity to the complexity of cultural communication within James’s court should ultimately complement the more nuanced picture of court politics and of James’s own role as a canny European royal politician that has begun to emerge in recent work.49

49About the author

-

R. Malcolm Smuts is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Massachusetts Boston, where he taught from 1976 to 2012. He has published books, articles, and edited volumes on various aspects of the cultural and political history of Britain and Europe during the early modern period, including Culture and Power in England, 1585–1685 (Macmillan, 1998), The Age of Rubens: Diplomacy, Dynastic Politics and the Visual Arts in Seventeenth-Century Europe (coedited with Luc Duerloo; Brepols, 2016), and Political Culture, the State and the Problem of Religious War in Britain, 1578–1625 (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Appendix

Footnotes

-

1

British Library (BL), London, Add MS 17677 G, fol. 375. ↩︎

-

2

Beaulieu to Trumbull, 21 December 1609, Trumbull MSS, alphabetical series, vol. 4, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Microfilm, LC041/Camb/195/1, fol. 73; De Groote dispatch, Christmas Eve 1609, Haus- Hoff- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna, Belgien, Repertorium P, Abteilung C, 44 (PC44), unpaginated. The Trumbull MSS are now in the British Library, whose manuscripts catalogue is currently available only on site; this has prevented me from supplying exact references. ↩︎

-

3

Trumbull MSS, vol. 4, fol. 76; BL, Add MS 17677 G, fol. 385r (a foliated nineteenth century transcript of the unfoliated original text of Dutch diplomatic correspondence with England, Nationaal Archief [The Hague] 1.01.02 Noel de Caron’s letter of 9 January 1610 – dated according to the Gregorian calendar still in use at the time in England and parts of the United Provinces – is reproduced and translated from this source as an appendix to this article); Thomas Birch, The Life of Henry, Prince of Wales (London, 1760), 143; The Letters of John Chamberlain, ed. Norman Egbert McClure, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939), 1:293. Birch lists the supporters as the duke of Lennox, the earl of Arundel, the earl of Southampton, Lord Hay, Sir Thomas Somerset; and the prince’s “instructor in arms” Sir Richard Preston. ↩︎

-

4

Trumbull MSS, vol. 4, fol. 76. The word “banquet” in this period could mean either a feast (as here) or a presentation of sugar confections that generally followed the main courses in such a feast, which Henry also provided. See Louise Stewart, “Social Status and Classicism in the Visual and Material Culture of the Sweet Banquet in Early Modern England”, Historical Journal 61, no. 4 (2018): 913–42. ↩︎

-

5

Warrant of February 1609 (i.e., 1610) to pay £2,986 9s. 7d. “for the charges about the Prince’s Barriers”, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, SO3/4; Warrant of 10 February to pay £1,986 9s. 7d. “for pearls, silks and other necessaries for the barriers”, TNA, SP14/52/30; Warrant to pay £673 3s. 9d. for the feast, TNA, SP14/52/57. It is not clear if the payment for “pearls, silks and other necessaries” was part of the general payment for “charges about the barriers”. TNA, SP14/52/63. ↩︎

-

6

For peers’ incomes see Lawrence Stone, The Crisis of the Aristocracy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), appendix 9, 762. For comparative costs of other court expenditures see R. Malcolm Smuts, “Art and the Material Culture of Majesty”, in The Stuart Court and Europe: Essays in Politics and Political Culture, ed. R. Malcolm Smuts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 86–112; the cost of Princess Elizabeth’s wedding (£93,000) and other major court ceremonies is discussed on pp. 93–94. ↩︎

-

7

Roy Strong, Henry Prince of Wales and England’s Lost Renaissance (London: Thames & Hudson, 1986), 141–55; Martin Butler, The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), ch. 6. ↩︎

-

8

Strong, Henry Prince of Wales, 141. Butler, while more circumspect, reaches a similar conclusion. Butler, The Stuart Court Masque, ch. 6. ↩︎

-

9

See, for example, Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly, “‘True and Historical Descriptions’? European Festivals and the Printed Record”, in Dynastic Centre and the Provinces: Agents and Interactions, ed. Jeroen Duindam and Sabine Dabringhaus (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 150–59; Marie-Claude Canova-Green and Jean Andrews, with Marie-France Wagner, eds., Writing Royal Entries in Early Modern Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013); and R. Malcolm Smuts, “Occasional Events, Literary Texts and Historical Interpretations”, in Neo-historicism: Studies in Renaissance Literature, History and Politics, ed. Robin Headlam Wells, Glenn Burgess, and Rowland Wymer (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000), 179–98. ↩︎

-

10

For a particularly striking continental example, see Anthony Colantuono, “High Quality Copies and the Art of Diplomacy during the Thirty Years War”, in The Age of Rubens: Diplomacy, Dynastic Politics and the Visual Arts in Seventeenth-Century Europe, ed. Luc Duerloo and R. Malcolm Smuts (Turnhout: Brepols, 2016), 111–26. ↩︎

-

11

Birch, The Life of Henry, 144–45; Letters of Chamberlain, 293. ↩︎

-

12

Marcello Fantoni, George Gorse, and Malcolm Smuts, eds., The Politics of Space: European Courts, ca. 1500–1750 (Rome: Bulzoni, 2009); Marcello Fantoni, Il potere dello spazio: principi e città nell’Italia dei secoli XV–XVII (Rome: Bulzoni, 2002). ↩︎

-

13

Roberta Anderson, “Foreign Diplomatic Representatives to the Court of James VI and I” (PhD thesis, University of the West of England, 2000), 116, 187, 189–90, 193–94, https://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/1443/1/Roberta%20Anderson%20thesis%202000.pdf. ↩︎

-

14

For his career see Alan Davidson, “Lewknor, Sir Lewis (c.1560–1627), of Selsey, Suss. and Red Cross Street, London; Later of Drury Lane, Mdx.”, The History of Parliament, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/lewknor-sir-lewis-1560-1627. Anderson discusses the prickly issues involved in diplomatic protocol at James’s and other early modern courts. Anderson, “Foreign Diplomatic Representatives”, 160–71, 185–96. ↩︎

-

15

Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 138; Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), Paris, Français 3505, fol. 20. ↩︎

-

16

I discuss these negotiations in R. Malcolm Smuts, Political Culture, the State and the Problem of Religious War in Britain and Ireland, 1578–1625 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 545–54. ↩︎

-

17

Smuts, Political Culture, 548; BnF, Français 3502, fol. 37. ↩︎

-

18

Hoboecke memorial “de ce qui est passé à l’endroit de mes audiences de la reine de la Grande Bretagne”, late 1606, Haus-, Hoff- und Staatsarchiv, Belgien PC44. ↩︎

-

19

Zúñiga is not named by Caron but he was serving as Spain’s ambassador at the time. ↩︎

-

20

BL, Add MS 17677 G, fol. 359v; BL, Harley MS 7002, fol. 95; Thomas Birch, ed., An Historical View of the Negotiations between the Courts of England, France and Brussels (London, 1749), 327–28. ↩︎

-

21

For the presents and conversations see BL, Add MS 17677 G, fols. 271v–272, 333r, 359v. ↩︎

-

22

Roberta Anderson, “Noel de Caron (b. before 1530, d. 1624)”, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/75021; Anderson, “Foreign Diplomatic Representatives”, ch. 5, esp. 274–85. ↩︎

-

23

Trumbull MSS, vol. 49, fol. 61; BL, Add MS 17677 G, fol. 376. ↩︎

-

24

For James’s European policies in this period see Smuts, Political Culture, ch. 11. ↩︎

-

25

Extract of Hoboque to De Groote, 18 August 1609, and De Groote dispatch, 10 July 1609, Haus-, Hoff- und Staatsarchiv, Belgien PC44. ↩︎

-

26

See, e.g., BnF, Cinq Cents de Colbert 426, fol. 9v. ↩︎

-

27

I have developed the analysis sketched here at much greater length and with supporting evidence in Smuts, Political Culture, 539–67, 593–96. ↩︎

-

28

BL, Add MSS 17677 G, fol. 377r. ↩︎

-

29

The following discussion is based on Caron’s letter of 9 January 1610, in the Inventory of the Archives of the States General, Nationaal Archief, 1.01.02, reproduced here in the appendix (see also n7). ↩︎

-

30

For a discussion see David Starkey et al., The English Court: From the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War (London: Longman, 1987). ↩︎

-

31

Simon Thurley, ed., St. James’s Palace: From Leper Colony to Royal Court (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022), 34–35. ↩︎

-

32

For the importance of clothing and jewels in the visual magnificence of the court see, Smuts, “Art and the Material Culture of Majesty”, 90–96. ↩︎

-

33

Birch, The Life of Henry, 144–45, gives the length of the table as 120 feet, so that each place setting must have occupied just over two feet if there were fifty-six seated on each side. This would have left about 13 feet for the dais and its steps, together with any void space at the far end of the room. ↩︎

-

34

A point originally analyzed by Per Palme, Triumph of Peace: A Study of the Whitehall Banqueting House (London: Thames & Hudson, 1957), and later much emphasized by Stephen Orgel, for example, in The Illusion of Power: Political Theater in the English Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975), 8, 9–17, 20–34. ↩︎

-

35

See Esther Mije, “The Dutch in Scotland: The Diplomatic Visit of States General upon the Baptism of Prince Henry”, in Rethinking the Renaissance and Reformation in Scotland: Essays in Honour of Roger Mason, ed. Steven Reid (Cambridge University Press, 2024), 269. Thanks to Dries Raeymaekers for calling my attention to this essay. ↩︎

-

36

For discussions of the use of sugar sculpture in Renaissance court banquets see R. I. M. Morris, “Receptions: Triumphal Entries, Ambassadorial Receptions and Banquets”, in Early Modern Court Culture, ed. Erin Griffey (London: Routledge, 2022), 238–39; and Ivan Day, Royal Sugar Sculpture: 600 Years of Splendour (Barnard Castle: Bowes Museum, 2002). ↩︎

-

37

John Nichols, ed., The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, 4 vols. (London, 1828), 1:473; Stephen Orgel and Roy Strong, eds., Inigo Jones: The Theatre of the Stuart Court, 2 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 1:284. While it is conceivable that the plates might have been sugar confections made to look like glass, Caron states that the banquet was “all laid out in crystal dishes and bowls”. This would be consistent with the practice of serving banquets given by peers and gentry on expensive and delicate platters, for which see Stewart, “Social Status and Classicism”; and Victoria Yeoman, “Speaking Plates: Text, Performance and Banqueting Trenchers in Early Modern Europe”, Renaissance Studies 31 (2017): 755–79. ↩︎

-

38

De Verteau dispatch, 22 January 1610, 19, TNA, PRO 31/3/41. ↩︎

-

39

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, Bescheiden Betreffende zijn Staatkundig Beleid en zijn Familie, 1570–1621, ed. S. P. Haak and A. J. Veenendaal, vol. 2 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1962), 398, 404; Antoine LeFèvre de La Boderie, Ambassades de monsieur de la Boderie en Angleterre (Paris, 1750), 55, 298–99. ↩︎

-

40

De Grote dispatch, 25 February 1610, Haus-, Hoff- und Staatsarchiv, Belgien PC45; La Boderie dispatch, 14 February 1610, TNA, PRO 31/3/41. ↩︎

-

41

BL, Add MS 17677 H, fols. 5v–6. ↩︎

-

42

Louis was eight years old at the time. He would technically reach his majority on his thirteenth birthday in September 1614, but would not be mature enough to take control of his kingdom and risk war with Spain for several more years. ↩︎

-

43

TNA, SP84/67, fol. 156. ↩︎

-

44

TNA, SP84/67, fol. 167. ↩︎

-

45

Among examples too numerous to list, see Roy Strong, Splendour at Court (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973); and Kevin Sharpe, Image Wars: Promoting Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010). ↩︎

-

46

For example, Tracey Sowerby and J. Craigwood, eds., English Diplomatic Relations and Literary Cultures in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, special issue, Huntington Library Quarterly 83 (2020); Karen Britland, “A Ring of Roses: Henrietta Maria, Pierre de Bérulle, and the Plague of 1625–1626”, in The Wedding of Charles I and Henrietta Maria, 1625: Celebrations and Controversy, ed. Marie-Claude Canova-Green and Sara J. Wolfson (Turnhout: Brepols, 2020), 85–104. ↩︎

-

47

A welcome exception is Jennifer Ng, “Breaking Bread with the Bedchamber: Feasting at the Court of James I of England, 1603–1625”, Explorations in Renaissance Culture 47, no. 2 (2021): 250–81. ↩︎

-

48

The concept of courtesy or courtly manners originally consisted for the most part of rules and protocols connected with the serving and eating of food in the presence of a prince or other dignitary, as shown by Anna Bryson, From Courtesy to Civility: Changing Codes of Conduct in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), ch. 1. A few studies of the English aristocracy pay attention to dining practices, for example, Felicity Heal, Hospitality in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990); and Stewart, “Social Status and Classicism”. Court feasting, at least in the early Stuart period, remains a neglected subject. ↩︎

-

49

Steven Reid, The Early Life of James VI: A Long Apprenticeship (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023); Alexander Courtney, James VI, Britannic Prince: King of Scots and Elizabeth’s Heir, 1566–1603 (London: Routledge, 2024); Smuts, Political Culture, chs. 3 and 8–12; Susan Doran, From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024); Eric Platt, Britain and the Bestandstwisten: The Causes, Course and Consequences of British Involvement in the Dutch Religious and Political Disputes of the Early Seventeenth Century (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015); Michael Questier, Dynastic Politics and the British Reformations, 1558–1630 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), chs. 5–7; Ralph Houlbrooke, ed., James VI and I: Ideas, Authority and Government (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006). ↩︎

Bibliography

Archive Sources

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Cinq Cents de Colbert 426.

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. Français 3505.

British Library, London. Add MSS 17677 G and 17677 H.

British Library, London. Harley MS 7002.

Haus- Hoff- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna. Belgien PC44 and PC45, unpaginated.

Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Microfilm LCO41/Camb/195/1.

Nationaal Archief, The Hague. 1.01.02. Inventory of the Archives of the States General.

The National Archives, Kew. PRO 31/3/41.

The National Archives, Kew. SO3/4.

The National Archives, Kew. SP14/52

The National Archives, Kew. SP84/67

Printed Works

Anderson, Roberta. “Foreign Diplomatic Representatives to the Court of James VI and I”. PhD thesis, University of the West of England, 2000. https://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/1443/1/Roberta%20Anderson%20thesis%202000.pdf.

Anderson, Roberta. “Noel de Caron (b. before 1530, d. 1624)”. In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2008. DOI:10.1093/ref:odnb/75021.

Birch, Thomas. An Historical View of the Negotiations between the Courts of England, France and Brussels. London, 1749.

Birch, Thomas, ed. The Life of Henry, Prince of Wales. London, 1760.

Britland, Karen. “A Ring of Roses: Henrietta Maria, Pierre de Bérulle, and the Plague of 1625–1626”. In The Wedding of Charles I and Henrietta Maria, 1625: Celebrations and Controversy. Edited by Canova-Green, Marie-Claude, and Sara J. Wolfson, 85–104. Turnhout: Brepols, 2020.

Bryson, Anna. From Courtesy to Civility: Changing Codes of Conduct in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Butler, Martin. The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Canova-Green, Marie-Claude, and Jean Andrews, with Marie-France Wagner, eds. Writing Royal Entries in Early Modern Europe. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013.

Chamberlain, John. The Letters of John Chamberlain. Edited by Norman Egbert McClure. 2 vols. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1939.

Cogswell, Thomas. The Blessed Revolution: English Politics and the Coming of War, 1621–1624. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Colantuono, Anthony. “'High Quality Copies and the Art of Diplomacy during the Thirty Years War”. In The Age of Rubens: Diplomacy, Dynastic Politics and the Visual Arts in Seventeenth-Century Europe. Edited by Luc Duerloo and R. Malcolm Smuts, 111–26. Turnhout: Brepols, 2016.

Courtney, Alexander. James VI, Britannic Prince: King of Scots and Elizabeth’s Heir, 1566–1603. London: Routledge, 2024.

Croft, Pauline. “The Parliamentary Installation of Henry Prince of Wales”. Historical Research 65 (1992): 177–93.

Davidson, Alan. “Lewknor, Sir Lewis (c.1560–1627), of Selsey, Suss. and Red Cross Street, London; Later of Drury Lane, Mdx.”. The History of Parliament. https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/lewknor-sir-lewis-1560-1627.

Day, Ivan. Royal Sugar Sculpture: 600 Years of Splendour. Barnard Castle: Bowes Museum, 2002.

Doran, Susan. From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024.

Fantoni, Marcello. Il potere dello spazio: principi e città nell’Italia dei secoli XV–XVII. Rome: Bulzoni, 2002.

Fantoni, Marcello, George Gorse, and Malcolm Smuts, eds. The Politics of Space: European Courts, ca. 1500–1750. Rome: Bulzoni, 2009.

Field, Jemma. Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Heal, Felicity. Hospitality in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Hinds, Allen. Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs Existing in the Archives of Venice. Vol. 15. London, 1909.

Houlbrooke, Ralph. James VI and I: Ideas, Authority and Government. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006.

La Boderie, Antoine LeFèvre de. Ambassades de monsieur de la Boderie en Angleterre. Paris, 1750.

Mije, Esther. “The Dutch in Scotland: The Diplomatic Visit of the States General upon the Baptism of Prince Henry”. In Rethinking the Renaissance and Reformation in Scotland: Essays in Honour of Roger Mason, edited by Steven Reid. Cambridge University Press, 2024. DOI:10.1017/9781805432210.014.

Morris, R. I. M. “Receptions: Triumphal Entries, Ambassadorial Receptions and Banquets”. In Early Modern Court Culture, edited by Erin Griffey, 231–54. London: Routledge, 2022.

Neville, Jennifer. “Dance”. In Early Modern Court Culture, edited by Erin Griffey, 478–93. London: Routledge, 2022.

Ng, Jennifer. “Breaking Bread with the Bedchamber: Feasting at the Court of James I of England, 1603–1625”. Explorations in Renaissance Culture 47, no. 2 (2021): 250–81.

Nichols, John, ed. The Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First. 4 vols. London, 1828.

Orgel, Stephen, The Illusion of Power: Political Theater in the English Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

Orgel, Stephen, and Roy Strong, eds. Inigo Jones: The Theatre of the Stuart Court. 4 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

Palme, Per. Triumph of Peace: A Study of the Whitehall Banqueting House. London: Thames & Hudson, 1957.

Platt, Eric. Britain and the Bestandstwisten: The Causes, Course and Consequences of British Involvement in the Dutch Religious and Political Disputes of the Early Seventeenth Century. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015.

Questier, Michael. Dynastic Politics and the British Reformations, 1558–1630. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Reid, Steven. The Early Life of James VI: A Long Apprenticeship. Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023.

Sharpe, Kevin. Image Wars: Promoting Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Smuts, R. Malcolm. “Art and the Material Culture of Majesty”. In The Stuart Court and Europe: Essays in Politics and Political Culture. Edited by R. Malcolm Smuts, 86–112. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Smuts, R. Malcolm. “Occasional Events, Literary Texts and Historical Interpretations”. In Neo-historicism: Studies in Renaissance Literature, History and Politics. Edited by Robin Headlam Wells, Glenn Burgess, and Rowland Wymer, 179–98. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000.

Smuts, R. Malcolm. Political Culture, the State and the Problem of Religious War in Britain and Ireland, 1578–1625. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Sowerby, Tracey, and J. Craigwood, eds. English Diplomatic Relations and Literary Cultures in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Special issue, Huntington Library Quarterly 83 (2020).

Starkey, David, D. A. L. Morgan, John Murphy, Pam Wright, Neil Cuddy, and Kevin Sharpe. The English Court from the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War. London: Longman, 1987.

Stewart, Louise. “Social Status and Classicism in the Visual and Material Culture of the Sweet Banquet in Early Modern England”. Historical Journal 61, no. 4 (2018): 913–42.

Stone, Lawrence. The Crisis of the Aristocracy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965.

Strong, Roy. Henry Prince of Wales and England’s Lost Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson, 1986.

Strong, Roy. Splendour at Court. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973.

Thurley, Simon, ed. St. James’s Palace: From Leper Colony to Royal Court. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022.

van Oldenbarnevelt, Johan. Bescheiden Betreffende zijn Staatkundig Beleid en zijn Familie, 1570–1621. Vol. 2. Edited by S. P. Haak and A. J. Veenendaal. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1962.

Watanabe-O’Kelly, Helen. “‘True and Historical Descriptions’? European Festivals and the Printed Record”. In The Dynastic Centre and the Provinces: Agents and Interactions. Edited by Jeroen Duindam and Sabine Dabringhaus, 150–59. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

Yeoman, Victoria. “Speaking Plates: Text, Performance and Banqueting Trenchers in Early Modern Europe”. Renaissance Studies 31 (2017): 755–79.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/msmuts |

| Cite as | Smuts, R. Malcolm. “Prince Henry’s Feast: Anglo-Dutch Relations and European Politics in Early 1610.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/msmuts. |