“Unseemly Caresses”

“Unseemly Caresses”: The Queer Style of James VI and I

By James Loxley

Abstract

In recent decades, the topic of King James VI and I’s sexuality has been discussed both more broadly and with less prejudicial bias than previously. However, while the idea of a gay James has become a familiar element in popular histories and cultural works, it continues to find some resistance in more academic history. This is at least partly because what might be sufficient evidence to convince a general audience is still seen as insufficient by many academic specialists. This has been followed by an unproductive division over the epistemic status of the king’s words, behaviour, objects, and deeds as evidence for a knowable sexuality, which risks overlooking the significance of that conduct and its material traces in and as themselves. The article revisits this conduct and these traces to go beyond either defining or refusing to define James’s sexuality. Instead, it proposes a reading of evidence as style, and in particular a queer style, that gives us a new way of looking at and understanding the distinctive erotics of James’s kingship.

Introduction

That James VI and I enjoyed sexual relationships with his male favourites has become an accepted commonplace of popular culture and general history in recent decades, after many years, even centuries, of unease, insinuation, disgust, and denial. Benjamin Woolley’s popular The King’s Assassin, published in 2017, accepts this claim as a key premise, and the 2024 Sky Atlantic–STARZ series based on Woolley’s book, Mary and George, emphasises the homoerotics of the king’s court with some enthusiasm and ample dramatic licence.1 James has also been included by Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller in the canon of Bad Gays, a “homosexual history” that focused on “the gay people in history who do not flatter us, and whom we cannot make into heroes”.2 Recent biographies of the king and of George Villiers, the most famous and infamous of James’s favourites, have taken James’s erotic involvement with a long line of male courtiers as a given, and even, in the case of Gareth Russell’s Queen James, as the organising principle of his life.3 In the popular historical imagination, the nature and substance of his erotic desires and behaviour now seem a settled matter.

1The same cannot be said, however, for academic history. Evidence for James’s sexual relationships with men was brought together most comprehensively by Michael Young in his James VI and I and the History of Homosexuality, published in 2000; his efforts were complemented by David Bergeron’s 1999 edition of the correspondence between James and (mostly) Villiers, which testifies to the extraordinary intimacy and familiarity of the two men’s interactions, including the latter’s seemingly definitive remembrance to James in an undated letter of “the time which I shall never forget at Farnham, where the bed’s head could not be found between the master and his dog”.4 Returning to the topic a decade later, however, Young notes what seemed to him a new disinclination among historians to interpret the evidence as he had done:

45In the late twentieth century … as the reputation of James trended upward, there was apparently a reticence to ascribe sex with other males to him. Meanwhile, Alan Bray’s influential work [referring to Bray’s later writing on male friendship rather than his 1982 book Homosexuality in Renaissance England], far from affirming James’s sexual relations with other males, portrayed those relationships as sexless. Scholars across the board adopted Bray’s thesis that James’s contemporaries misread the signs, wrongly seeing sodomy where there was only friendship. A flood of books and articles analyzed the sodomitical discourse that swirled around James while suspending judgment about whether that discourse was rooted in reality.5

Young would no doubt find confirmation for this thesis in the recent contribution of Noel Malcolm, who firmly dismisses the sexual interpretation of James’s relationship with his favourites as a misreading of the signs of non-sexual male friendship, affection, and favour—which is actually a much blunter claim than Bray’s.6 What for Young is proof of sexual activities and relationships is for others no such thing: for example, Michael Questier has recently insisted that “the question of James’s alleged homosexuality is, in the sense of actual evidence, a historical nonissue”.7 Malcolm and Questier are not disputing that Young, and others who share his opinions, have assembled material that might be suggestive of homoeroticism and of sexual behaviour; they are, however, adamant that this is not something that can be known through such materials, and cannot therefore properly be described as “evidence” in a strict sense. The difference, in other words, lies in what is necessary for something like sexuality to be known. Where Young avers that he has exactly what he needs for knowledge to be established, his demurrers contest precisely that point.

6This article is not an attempt to settle the question of whether or not James had sex with some of his male courtiers. But it is not a sceptical withdrawal from the answerability of that question either, nor is it animated by a strictly historicist injunction against attributing “sexuality” in the modern sense to premodern historical subjects. It seeks, rather, to explore the basis for the question’s terms and the impulsion they bring with them: the specific organisation of the reading of behaviour as the interpretation of “signs”, in ways that continue to structure both popular and some academic responses. In so doing, I hope to make some space for a reading of James’s conduct as style, and as a style for which the term “queer”—both as a mode of erotic conduct at odds with social norms and as a challenge to our very understanding of what constitutes sexuality—is a fitting label.

The Epistemology of the King’s Closet

Apethorpe, a Northamptonshire country house with a troubled modern history, has particularly strong associations with King James. Throughout his reign James was a regular visitor, hosted by Sir Anthony Mildmay until the latter’s death in 1617, and then by Mildmay’s son-in-law, Sir Francis Fane.8 It was here, on 3 August 1614, that James is said to have first met his greatest favourite, George Villiers. From 1622 to 1625, in accordance with a request from the king, which Fane may well have encouraged, part of the house was remodelled and a new wing constructed on its east side to create a suite of apartments suitable for royal use.9 At the same time, an almost life-size statue of the king was installed in the facade of the south range, ensuring that James presided over the house even in his physical absence.10 The layout reflected elements of spatial design from state apartments elsewhere, thus accommodating not just royal visitors but also the forms of daily life appropriate to their station.

8

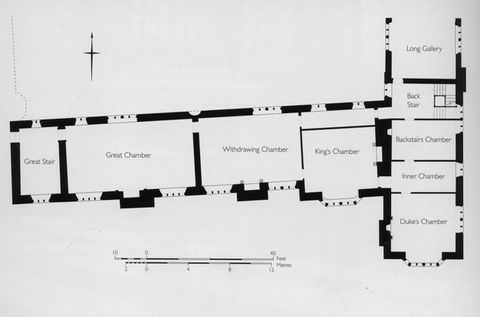

The section of these apartments incorporating the royal guests’ bedchambers was much altered in subsequent centuries, and when Apethorpe was rescued and restored by English Heritage in the first decade of this century a short passage, or long doorway, between the King’s Chamber and an Inner Chamber was unblocked (fig. 1). On either side of this Inner Chamber were two rooms designated in an inventory of 1629 as the Backstairs Chamber and the Duke’s Chamber; the former connected these inner rooms to the back stair and the Long Gallery, while the latter was a secondary bedchamber.11 These four rooms together constituted the most secure and least publicly accessible accommodation in the apartments; during a royal visit, one of the three rooms behind the King’s Chamber would have functioned as the royal closet.12 The secondary bedchamber’s 1629 designation as the Duke’s Chamber hints at its use to accommodate Villiers, duke of Buckingham after 1623, most likely during James’s final visit to Apethorpe in 1624. This room is decorated with a chimneypiece featuring a carved relief of an English galleon and a cartouche from which two arms are extended, one holding an anchor and the other what is plausibly a ducal coronet—all emblems suited to Buckingham, who was Lord High Admiral from 1619 (fig. 2).13 However, the cartouche itself contains the Prince of Wales’s feathers, which associates the room additionally with Prince Charles, who also had significant naval interests and responsibilities. Therefore, its occupant or occupants in 1624, and the implications for royal intimacies that might follow from knowing who stayed there, are not so easily determined.

11

Nonetheless, when the restoration of Apethorpe received media attention in the summer of 2007, the findings were framed in a recognisable fashion. The blocked doorway was described as “a suggestive clue to a 400-year-old royal scandal” and “a secret hidden for hundreds of years”—“a secret pair of connecting doors, bricked up centuries ago, which directly linked the bedrooms of James and George [Villiers]”.14 Of chief interest to me here is the emphasis on secrecy, a secrecy that is of course the precondition for any scandal, since scandal consists at least in part of its failure or its breach. The doorway between the King’s Chamber and the Inner Chamber (not the Duke’s Chamber) was not actually secret; it was essential to the functioning of this group of rooms, and was ornamented and decorated rather than hidden (fig. 3).15 That it was later bricked up was a result of the house’s changing uses, not of concealment; to describe it as a secret exposed is to invert its history. But in this framing, such an inversion is clearly irresistible because secrecy and concealment are key to the ways in which the intersection of James’s personal life and kingly reign have been articulated over the centuries.

14

This is most evident in the influence of Walter Scott’s Secret History of the Court of James the First, published in 1811, on the understanding of Jacobean rule. As Hilary Clydesdale argues, Scott’s interest in the genre of anekdota, or secret history, was a significant element in his practice of historical fiction and a key aspect of his historiographical sensibility.16 The seventeenth-century histories of James’s reign that Scott brings together in his two-volume edition occupy “a middle character between History and Memoirs, … neither presenting the systematized form and dignified elevation of the one, nor the connected narrative and detail of the other”.17 Central to this mixed genre was precisely what Scott here calls “curious facts” and “minute particulars worthy of preservation”—the anecdotes on which the genre of secret history was predicated. Anekdota translates literally as “unpublished matters”, and the association of such curious facts and minute particulars with the unconcealing work of secret history stems from the account of the life and times of the Emperor Justinian written by the sixth-century historian Procopius, which was first translated into modern vernacular languages in the early modern period. Anekdota, as Rebecca Bullard says, “peers into cellars, closets, and bedchambers to reveal the personal and political weakness and corruption of the Emperor Justinian and his General Belisarius”.18 The anecdote in this sense furnishes eye-catching material for a revealing counter-history that exposes a hidden truth or concealed knowledge to public view. It is the counter-historical force of such anecdotes that Scott found attractive: to preserve and, more importantly, to publish those curious facts and minute particulars was to undertake to expose the secrets that an official history would seek to keep concealed. The texts that Scott republished were first printed in the mid-seventeenth century, their publication motivated by the value of such counter-histories to the sustained polemical assault on the image of the first Stuart kings of Britain launched in the later 1640s. Milton’s Eikonoklastes, a relentless takedown of the Eikon Basilike, attributed to Charles I, is perhaps the best-known contribution to this campaign. In the 1650s, with Charles’s surviving sons still a threat, the whole Stuart dynasty had become a legitimate target for the defenders of the Commonwealth.

16The historiography of the Jacobean court is still marked by this construal of knowledge as the uncovering of anecdotal secrets. In The Murder of King James I, Alastair Bellany and Thomas Cogswell emphasise the extent to which this discourse of secrecy is continuous with the political culture of libel in the early modern period, while also sustaining what we might call an epistemology of libel within their own framing.19 Bellany and Cogswell anatomise the processes by which dangerous claims circulated and the broader reasons for their doing so. At the same time, they give those claims new prominence even if they do not credit them, and they become once again discursively typical not just of what we know about King James’s court and reign but also of the form that such knowledge continues to take. The texts by Francis Osborne, Anthony Weldon, and Edward Peyton that make up the bulk of Scott’s Secret History draw extensively on the swirl of rumours and insinuations that constituted a culture of libel, fusing historiography and polemic. And no one should be in any doubt about the pertinence of a culture of libel to James’s reign. One of the more quixotic strands of his later years was his determination to pursue, expose, and punish the pseudonymous author of Corona Regia, a notorious mock panegyric of the king that concentrated a wide array of attacks and slanders on him and his English predecessors, and expressly framed its mock praise as an appreciation of the royal need for secrecy. “It is truly remarkable”, the Corona states, “how much shameful and immoral behaviour can be obscured in a king by the public expression of a calm and moderate temperament”. Or, more bluntly, “those who know you, wondrous king, do not know you at all”.20

19As the Corona’s emphasis on “shameful and immoral behaviour” both here and throughout indicates, there is a singular force within this association of James and secrecy—and this is where the epistemology of libel is indissolubly entwined with the epistemology of the closet. The key element here is transgressive sexuality—in contemporary libels such as the Corona and in much of the subsequent biographical and historical attention the king has received, such sexuality is perhaps the chiefest of the king’s secrets, and the key focus of the compulsions both to conceal and to expose that constitute the secret as such. In Eve Sedgwick’s classic account, the epistemology of the closet is the production of sexuality as knowledge through modern regimes of power, one of Michel Foucault’s key contentions in the first volume of his History of Sexuality. The entwinement of sex and knowledge is, of course, an ancient thing: “a process”, Sedgwick says,

21protracted almost to retardation, of exfoliating the biblical genesis by which what we now know as sexuality is fruit—apparently the only fruit—to be plucked from the tree of knowledge. Cognition itself, sexuality itself, and transgression itself have always been ready in Western culture to be magnetized into an unyielding, though not unfissured, alignment with one another.21

This long history, for Sedgwick, crystallised over the course of the nineteenth century into a dynamic of the production of truth as sexuality and the vigorous repression—the consignment to secrecy, to the closet itself—of male same-sex desire. This “particular sexuality”, Sedgwick notes, “was constituted decisively as secrecy”.22

22Of course, the contexts in which modern sexual identities were constituted as knowledge are very different from those of early modernity. According to a somewhat basic reading of Foucault’s genealogy, the homosexuality of modernity is not easily identified with premodern sodomy, insofar as the former is an identity (whether pathologised or not) and the latter a sin or crime. Scholars such as David Halperin, Valerie Traub, and Bruce Smith have given us plenty of reasons to be doubtful of the usefulness of this schema, and Sedgwick herself has noted that the premodern concept of sodomy is itself bound up in this epistemology of secrecy.23 The discourse of sodomy in early modernity is in tension with itself in a way that binds it into considerations of knowledge and of the knowable. On the one hand, as Noel Malcolm has recently insisted, sodomy has a reasonably precise cultural, doctrinal, and legal meaning in early modernity; on the other, however, it is at the same time consistently occluded as an unspeakable or unnameable sin that cannot be explicitly defined and therefore made the proper object of any schema of knowledge.24 The truth of sodomy can never quite be revealed in toto; the word “sodomy” names both a practice and its concealment, such that secrecy is part of its truth and the “practice” itself expands in cultural possibility even as its legal meaning is contracting into a more precise definition

23We can see this more clearly perhaps through one well-known example. The Puritan polemicist Philip Stubbes declared in a perhaps over-cited passage from his 1583 tract The Anatomie of Abuses that stage plays encourage sodomy, but this declaration is marked by an unavoidable or necessary displacement of a proper referent. As he put it, “than [i.e. then] these goodly pageants being done, every mate sorts to his mate, every one bringes another homeward of their way verye freendly, and in their secret conclaves (covertly) they play the Sodomits, or worse”.25 The triple tautology of the insistence on concealment here—“secret conclaves (covertly)”—may be thought to overegg the pudding, but that final “or worse” whisks in yet more egg. James Bromley has suggested that here Stubbes adds something to an already defined sodomy, namely “certain affective relations that eventually became illegible under the rubrics of modern intimacy”, and there is undoubtedly merit, in King James’s case, of paying attention to the variety of affective relations to which his behaviour might approximate, as I hope to show.26 However, in the context of the insistence on secrecy, it more plausibly denotes sodomy’s necessary resistance, in this epistemological frame, to being named or known even as its truth is demanded—or, to put it another way, sodomy’s constitutive excess over its own definition. It is not enough for a secret to be revealed or a truth to be known; it must continue to be produced as a secret or continue to be sought as an always hidden truth.

25A further implication of this process is that sodomy’s unspeakability both conceals and circulates it, as Danielle Clarke has argued:

27at the point at which sodomy might be disclosed, it is always located elsewhere, legible only through the signs of other discourses, in particular classical myth, the conventions of courtiership and the language of friendship, but also within a semantic field packed with overlapping and overdetermined nouns: minion, catamite, favourite, creature, ganymede, siren, damon, ingle, special friend.27

In James’s case, it structures criticism of both his use of favourites throughout his reign and his broader apparent failings as a man and a king. Such a circulation or proliferation means that the often implied or displaced figure of sodomy is at work in so much of what is familiarly claimed to be known about his life, his court, and his reign—and in how we claim to know it, as well as in the construal of such knowledge as the necessary object of enquiry. Even when academic historians express frustration with the continuing interest in “the homosexual issue” in James’s biography or reputation, as Jenny Wormald terms it, much preferring to change the subject, they implicitly acknowledge the shaping force of this way of construing what it is we most want to know. The epistemic framework of the secret history continues to organise our approach to this king and this man.

Insofar as James VI and I is a subject of secret history, and the secret is to be found in his closet (whether at Apethorpe or elsewhere), and that secret is homoeroticism as a mode of sexual transgression, our efforts to know the king have been, and will always be, bound up with this complex of issues and will also prove structurally irresolvable. This, I suggest, is why the debate around the king’s sexual desires and behaviours is ultimately unproductive: both the anekdota that serve as our evidence and the historiographical assumptions we bring to bear on that evidence are structured by an epistemology of the royal closet that necessarily anchors knowledge in (un)concealment. Once again, to say this is not to make a sceptical claim about the necessary limits of historical knowledge or an empirical claim about the absence of sufficient or persuasive evidence. It is perhaps a prompt to approach the topic in a different fashion.

The Stage and the Tiring House: King James and the Public View

One of the better-known passages from Francis Osborne’s secret history of James’s reign explicitly invokes an epistemology of the royal closet. In the middle of a passage criticising the king’s behaviour towards his favourites, Osborne asserts that James himself was responsible for the accusations of sodomy sometimes levelled against him:

28Nor was his Love, or what else posterity will please to call it (who must be the Judges of all that History shall informe) carried on with a discretion sufficient to cover a lesse scandalous behaviour; for the King’s kissing them after so lascivious a mode in publick, & upon the Theater as it were of the world, prompted many to Imagine some things done in the Tyring house, that exceed my expressions no lesse then they do my experience: And therefore left floting upon the waves of Conjecture, which hath in my hearing tossed them from one side to another.28

There is a lot going on here. First, Osborne names sodomy itself as unnameable: he qualifies “Love” with an indeterminate “what else”, the definition of which must be left to posterity; declares that “some things” he specifies nonetheless exceed both expression and experience; and surrenders them to an indeterminate “conjecture” that is quite carefully determinate. Second, we witness here the secret history’s demand for a subject’s inner or hidden essence, its conformity to the unconcealing logic of “scandal”, and for a revealed truth that is necessarily sexual. As the metaphor of stage and tiring house (the backstage space used by actors for costuming) makes clear, James’s visible behaviour towards his favourites points inexorably to the sodomy that is somehow entirely evident yet still hidden and unnamed.

However, the lack of “discretion”, for which he appears to be criticising James, is potentially an issue for his imposition on him of the problematics of concealment, since—to state what ought to be obvious—the tiring house is not a closet within a single plane of knowable public and private places but is ontologically distinct from the stage: it belongs to a different order of reality. Osborne wants to gesture towards the hidden truth of James’s behaviour, but at the same time he notes or concedes that no significant truth is hidden at all, in the same way as characters on stage have no offstage or backstage reality. The king’s lascivious behaviour, his affective relations (to use Bromley’s term), are displayed on stage and in public and conceal nothing at all. In this situation, any epistemic design to know or expose a truth would be redundant; whatever the king hides, it is not his erotic self. From this standpoint, the main implication of Osborne’s attack seems to be not so much that the king was really or secretly a sodomite, but that James had failed to make a secret of his affections. In perhaps similar fashion, again despite its adherence to the protocols of secret history, Weldon’s notorious sketch of James’s appearance and conduct also insists that “his Character”, with all its defects, “was obvious to every eye”.29

29This is, in potentia, a powerful counter to the epistemology of the king’s closet. Osborne and those who echo the ostensibly truth-revealing protocols of secret history today invite us to interpret James’s kisses, and to interpret them specifically as the external signs of hidden behaviours that define the king’s character. But the unrestrained visibility of James’s behaviour, which Osborne also wants to acknowledge, resists this way of knowing and defies its claim to reveal a hidden truth. What makes the king’s character distinctive or remarkable is not concealment but display. As is well known, the theatrical metaphor was anticipated repeatedly by James himself and in ways that run counter to Osborne’s suggestion of an interpretative relation between the visible and the hidden. As he famously put it in the 1603 Edinburgh edition of Basilikon Doron:

30But as this is generally trew in the actions of all men, so is it more specially trew in the affaires of Kings: for Kings being publike persons, by reason of their office and authority, are as it were set (as it was said of old) upon a publike stage, in the sight of all the people; where all the beholders eyes are attentively bent to looke and pry in the least circumstance of their secretest drifts: Which should make Kings the more carefull not to harbour the secretest thought in their minde, but such as in the owne time they shall not be ashamed openly to avouch; assuring themselves that Time the mother of Veritie, will in the due season bring her owne daughter to perfection.30

The metaphor of the public stage is here deployed to refuse the imputations of secrecy at work in Osborne’s invocation of the tiring house. Indeed, the whole of this address “To the Reader” is organised around the issue of secrecy and the requirement for kings specifically to avoid being caught up in its epistemological framing. Indeed, James claims that he is now publishing Basilikon Doron to foil such framings, “as well for resisting to the malice of the children of envie, who like waspes sucke venome out of every wholsome herbe; as for the satisfaction of the godly honest sort, in any thing that they may mistake therein”.31 In his speech to both Houses of Parliament on 21 March 1610, he referred back to this passage, asserting that “I hope neuer to speake that in private, which I shall not avow in publique, and Print it if need be”, in the course of an oration which he had already declared his intention to “set Cor Regis in oculis populi”.32 And in 1622 he published a declaration accompanying his proclamation dissolving Parliament that again imagines him on stage, “obvious to the publike gazing of every man”, “represented unto all men without vaile or covering”, “as were Wee all transparent, and that men might readily passe to Our inward thoughts, they should there perceive the self-same affections which Wee have ever professed in Our outward words and Actions”.33 As such passages demonstrate, James’s published conception of royal performance was one that refused the imputation of hiddenness or secrecy: the king’s heart and affections were what his people saw. This was not just a feature of his writing either, and it was remarkably consistent throughout his life. In a letter of July 1584, Albert Fontenay recorded and enacted James’s wish to be represented in cipher as a heart, while a surviving contemporary miniature of James, attributed to Lawrence Hilliard and probably dating from more than thirty-five years later, features his portrait in a heart-shaped frame (fig. 4).34

31

This ought to have consequences for how we read the king’s performance of affection towards his favourites. As many scholars have noted, the discourse of royal favouritism in early modernity was particularly fraught, caught up as it was in anxieties about tyranny, misrule, and the displacement of the public good by the libidinal demands of a corrupted ruler; in the case of male monarchs too, the possibility of sodomy is always lurking.35 The young James, it seems, learned the value and uses of favouritism from Esmé Stuart, lord D’Aubigny and earl of Lennox, in Scotland at the turn of the 1580s; D’Aubigny was familiar with its enthusiastic deployment by Henri III at the French court and with the particular institutional structuring of the court that it required (and that James adapted).36 Steven Reid has argued that D’Aubigny provided James with something he had never had before: a power base distinct from the noble factions that had dominated his minority, loyal followers whose authority derived solely from their status as recipients of royal favour.37 His rule in England replicated both the practice and its supporting institutional structures at court, endowing favourites with wealth and status and—crucially—control over access to the king himself.38 This was, in other words, policy—a dimension of the practice that the contemporary critiques of favouritism as signifying a loss of kingly self-control inevitably obscured or denied. James did not make a favourite of every comely young man placed in his path; the making and unmaking of favourites was a process that called for collaboration and even consent from the most important people around him, including Queen Anna.39

35The key point is that a favourite’s power at court and in politics depended entirely on the visibility of the king’s favour, and this necessarily took affective and interpersonal forms as well as including the bestowal of land, wealth, and titles. As Christiane Hille suggests:

40the unique power of the favourite sprang from his proximity to the monarchic body. His power was contingent upon the concept of sovereign monarchy as it stressed the ideology of personal rule and negotiated political power through the regulation of physical proximity to the body of the monarch. Displays of bodily intimacy thus served as essential expressions of patronage bonds that circulated power between the members of a predominantly homosocial court.40

The gestures of intimacy that observers reported from the time of D’Aubigny onwards were indeed public actions, precisely “displays” in that they were meant to be seen. Sir Henry Widdrington’s 1582 report of James “clasp[ing D’Aubigny] about the neck with his armes and kiss[ing] him” makes a point of remarking that this behaviour was public, “in the oppen sight of the people”, as if James’s putting it on show, as much as the kissing itself, was especially noteworthy.41 Similarly, Lord Thomas Howard’s 1607 account of Robert Carr’s embrace as a favourite noted how James “leaneth on his arm, pinches his cheek, smoothes his ruffled garment, and, when he looketh at Carr, directeth discourse to divers others”.42 Those others were certainly meant to note what they were seeing, and Howard was describing this to his correspondent Sir John Harington so that the latter might understand where the route to royal beneficence now lay. Similarly, Simonds D’Ewes recorded in his diary several stories told him by a friend in January 1622, all of which demonstrate James’s fondness for Buckingham. One anecdote was of James calling out “Becote [i.e. by God] George I love thee dearly” while the favourite and his wife were dancing at the performance of Ben Jonson’s and Inigo Jones’s Masque of Augurs on Twelfth Night that year. Another described how James waited for Buckingham at chapel in Whitehall the same day—an inversion, of course, of the usual practice, where subjects waited on and for monarchs—then, when Villiers finally came over to him, James “fell upon his necke without anye moore words”. A third recounted James’s behaviour at Christmas 1621, during a game of cards between Buckingham, his mother, his wife, Prince Charles, and the earl of Rutland, when the king apparently “openly professed” his love for everyone at the table.43 Such anecdotes have been recounted primarily as evidence for the sexual nature of James’s relationship with Buckingham, but clearly what D’Ewes and his informant thought most significant about them was that they “argue[d] his [Buckingham’s] greatness”.44 For the king to “openly profess” his love for Villiers in this fashion was read primarily as a striking demonstration of the favourite’s pre-eminence in royal esteem, even though D’Ewes was undoubtedly aware of, and by August 1622 was happy to give credence to, the claims that James’s behaviour was indeed sodomitical.45 In other words, the audible and visible bestowal of affection was a political gesture and not just a personal one. This was something James was happy to symbolise as well as enact. In a January 1617 letter to William Trumbull, the diplomat to whom he had assigned the thorny task of identifying the author of Corona Regia, John Castle noted that the king’s gift to Villiers at his elevation to the title of earl of Buckingham was “his Majesties owne picture with his hart in his hand”.46 Here, the display of the king’s heart was not just a mark of royal openness but the putting on show of his favour as love or affection.

41This emphasis on the public nature of his affections should be enough to establish that James knew exactly what he was doing and therefore the risks he was running. As the case of Corona Regia shows, he was certainly aware of the nature of slanders circulating about him and appreciated the threat to the royal dignity they could pose. He had demonstrated just such an awareness in his dealings with Edinburgh ministers of the kirk as early as 1592, when he showed them “contumelious verses made in contempt of him, calling him Davie’s sonne, a bougerer [i.e., buggerer], one that left his wife all the night intactam; contemnit numina, sponsam etc. … ‘Yee may see’, said the king, ‘what they meane to my life, that carie suche libells about them. I thought good to acquaint you with these things, that ye may acquaint the people with them, for they have a good opinion of you, and credit you’”.47 Nearly thirty years later, the king’s poem “The Wiper of the Peoples Teares” was written as a detailed rebuttal of charges contained in “a Libell lett fall at Court”, inveighing not just against this specific “libel” but also against the circulation of “railing rhymes and vaunting verse” that directly discussed matters of state.48 James’s anti-libel contains a direct defence of Buckingham, who was by this point the focus of loud opposition, much as James’s practice of favouritism was itself an object of acute hostility among his critics.49 That the king should take it on himself to rebut an anonymous critic in the same form in which such criticism circulated is revealing of his alertness not only to what was said about him but also to how it was purveyed and received. It is worth noting that James had earlier intervened in public debates about the meaning of the ominous comet that appeared in the sky in the autumn of 1618 with a poem attempting to deflect or block certain hostile or negative interpretations of the portent.50 Those concerned with prognostication should keep their “rash Imaginations” to themselves, the king suggests, reserving them for fevered sleep or idle gossip:

47Then let him dreame of Famine plague & war

And thinke the match with spaine hath causd this star

Or let them thinke that if their Prince my Minion

Will shortly chang, or which is worse religion

And that he may have nothing elce to feare

Let him walke Pauls, and meet the Devills there.

If James’s awareness of the kinds of concerns that might be troubling his more excitable subjects is notable, so too is his apparent ease in describing his favourite as his minion, a word with persistent sodomitical connotations in the context of verse libels. In which voice does this poem speak? That of the king or of his potentially impertinent or libellous subject? Is “minion” James’s term or that of his enemies? Perhaps it doesn’t matter. Whichever it is, the poem shows ample awareness of how his kingly practices might be received.

Reading the King’s Affections

It is clear that some of James’s contemporaries found his affective displays of favour distinctive and noteworthy, in both their specific form and their public nature, at least to the extent that they noted them in writing. For some of the secret historians, and those more modern scholars who have followed them, these actions amount to “unseemly Caresses”, as one eighteenth-century commentator put it, and they did not scruple to disguise their own antipathy to such conduct and to its public nature; moreover, this antipathy is predicated on the assumption that the king’s behaviour is to be read through the matrix offered by the figure of sodomy as sexuality.51 This is the epistemology of the king’s closet in action, and it leads directly to the irresolvable question of whether what we know about James’s disposition means that he had sex with other men. One of the key problems for the secret history framing of James’s conduct, as I have sought to show, is the tension between claiming to unconceal the king’s hidden shame at the same time as recoiling from his shamelessness, and then insisting that only some of what the king puts on show so extravagantly is evidential—a presupposition masquerading as a conclusion. Not entirely dissimilar is an approach that seeks to know King James through and as his same-sex desire but reads his affectively charged public behaviour only in the mode of evidence for that desire. This not only risks the withdrawal of the truth it is seeking to unveil (since such “evidence” can always be interpreted otherwise, and some anecdotes count more than others) but also, and more significantly, is likely to miss or underplay the double significance of behaving like that and doing so in “oppen sight”.

51In seeking to establish his case for the sexual nature of James’s relationship with D’Aubigny, for example, Michael Young makes much of the allegations levelled, during D’Aubigny’s residence in Scotland, by alarmed nobles, churchmen, and English agents, who feared not only his power with the young king but also his ties to France and his susceptibility to Catholic influence. As Francis Walsingham bluntly summarised, the English believed that D’Aubigny’s “coming out of France was to no other end but to work a division between England and Scotland, thereby the better to establish the Romish religion in Scotland”.52 Young’s account marshals these allegations as further evidence for a sexual relationship between D’Aubigny and James, seemingly signalled by the clasping and kissing Widdrington had noted in May 1582. Of course, James’s behaviour towards his older cousin appeared noteworthy precisely because of the transgressive combination of intimacy, familiarity, and publicness, as Widdrington’s anecdote shows. But the accusations of sexual corruption and licentiousness against D’Aubigny and his partisans at this time are wide-ranging, as Young acknowledges.53 Only nine days after writing the letter to Walsingham in which he remarked on the king’s bodily conduct with D’Aubigny, Widdrington sent a further letter to the same recipient elaborating on the concerns of the kirk. The summary of this letter as quoted by Young states baldly that “the ministry are informed that the Duke [i.e., D’Aubigny] goes about to draw the King to carnal lust”, but the full document is more complicated.54 Widdrington actually noted the churchmen’s concern that:

5255both the Duke and Arrain goe about to drawe the Kinge to carnall lust, wherfore thei are in great feare if he should be infected therwith, that the Duke should the rather bring his divelyshe practises the better to passe, for that thei think the King wold not so well lyke of sermons, whenne he should heare his fault and sinne reproved.55

The involvement here of D’Aubigny’s sometime ally, James Stewart, earl of Arran, was significant; one of the chief targets for ecclesiastical shaming was his wife, Elizabeth, who had divorced the former earl of Lennox, Robert Stewart, in May 1581, to marry Arran two months later when she was already pregnant with their child.56 Indeed, in the justification for their actions produced by the Ruthven raiders who took James captive in August 1582, she was singled out for abuse:

5657What sall we speeke of the shamelesse and filthie behaviour of her that is called Countesse of Arran, who, not being satisfied with the ignominie and shame done to the Erle of Marche, the king’s dearest uncle, through her inordinat lust, ceasseth not yitt to pervert the king’s Majestie’s owne youth, by slanderous speeche and countenance, which are ashamed to expresse?57

The declaration also accused D’Aubigny, Arran, and his wife of “corrupt[ing] the king’s age, giving him all the provocatiouns to dissolute life in maners that was possible, by licentious companie, by interteaning of their owne harlots in his presence, and careing them about with them to all places where his Hienesse did repaire”.58 The raiders’ clerical allies, meanwhile, denounced D’Aubigny for “introducing of prodigality and vanitie in apparell, superfluitie in banketting and delicat cheere, deflowring of dames and virgins, and other fruicts of the Frenche court”.59 The point was not that homoeroticism was absent from the picture—given Henri III’s fondness for his “mignons”, it is probably implied in “other fruicts”—but that it was just one of several blatant instances of depravity with which the king’s favourite and his allies could be charged and which the indeterminacies of sodomy could contain. James’s “unseemly” behaviour, as noted by Widdrington, is to be read as part of a general pattern of visibly sexualised transgression, to which the king, in the view of those who took it on themselves to “rescue” him, was alarmingly vulnerable.

58Young’s account of the allegations against James and his party acknowledges their erotic scope, but in his eagerness to interpret all this as evidence of a sexual relationship between James and D’Aubigny he has no choice but to dismiss that scope as evidentially insignificant, in contrast to aspects of James’s conduct that might be interpreted solely as evidence of same-sex desire.60 In this his approach echoes that of writers such as Osborne, who similarly privileged some elements of James’s public behaviour at the expense of others. In his history Osborne noted one occasion on which the king parted with the queen with an excessive affective display: “he did at her Coach side take her leave, by Kissing her sufficiently to the middle of the shoulders, for so low she went bare all the daies I had the fortune to know her”.61 But his prefatory gloss to this anecdote insists that some of the affective behaviour James performed on the public stage did not indicate what actually went on in the tiring house: this display of affection was merely to “shew himself more uxorious before the people at his first coming in than in private he was”.62 As with Young’s insistence that the broader allegations of sexual misbehaviour made against D’Aubigny should be considered unimportant, the sorting of behaviour here into the evidential and the insignificant or deceptive is exactly what the epistemology of the king’s closet demands.

60We can see the same kind of pattern at work in the interpretation of another example of the king’s conduct shortly after James acquired the English throne. Paul Hammond has noted the possible homoerotic implications in an exchange over the emblematic device borne by Sir Philip Herbert during the New Year’s celebrations of 1604, as recorded by Dudley Carleton in a letter to John Chamberlain. Herbert’s device identified him as “a colt of Bucephalus’ race, [who] had this virtue of his sire that none could mount him but one as great at least as Alexander. The king made himself merry with threatening to send this colt to the stable, and he [i.e. Herbert] could not break loose till he promised to dance as well as Banks his horse”.63 That Herbert’s device should be singled out, and in this manner, is undoubtedly significant: it suggests not only an innuendo-laden verbal exchange between the two men but also that James grabbed hold of Herbert, which is perhaps why Carleton thought it especially noteworthy. Hammond couples it with Carleton’s account in a letter to Ralph Winwood of James’s behaviour at Herbert’s marriage to Susan de Vere on 27 December 1604, almost a year later, which he cites from an annotation in Scott’s Secret History.64 The newlyweds were “lodged in the Councill Chamber, where the King in his Shirt and Night-Gown gave them a reveille-matin before they were up and spent a good time in or upon the Bed, chuse which you will believe”.65 Scott noted this behaviour as an instance of the “odd familiarities which James used with his favourites … which were, to say the least, most disgusting and unseemly”, and Hammond interprets it as indicating James’s ongoing erotic interest in Herbert.

63A sentence from Carleton’s letter to Winwood preceding the passage excerpted by Scott complicates this reading. Carleton says that, at the marriage service, “the King gave her, and she in her Tresses, and Trinketts brided and bridled it so handsomly, and indeed became her self so well, that the King said, if he were unmarried he would not give her, but keep her himself”.66 With this in mind, the “unseemliness” in James’s conduct towards both bride and groom cannot simply be interpreted as of a piece with the homoerotic interplay of the previous year: the informally dressed king who climbed onto or into the nuptial bed had already articulated an erotic interest, however jestingly, in both of them. Indeed, it was probably both the generalised erotic potential in this familiarity or intimacy, and its undisguised, overt nature, that were transgressive or unseemly. What Carleton finds so worthy of note here is the highly visible combination of informality, intimacy, and ribaldry that marks the king's conduct.

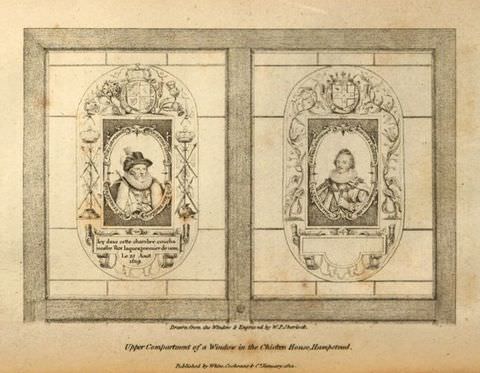

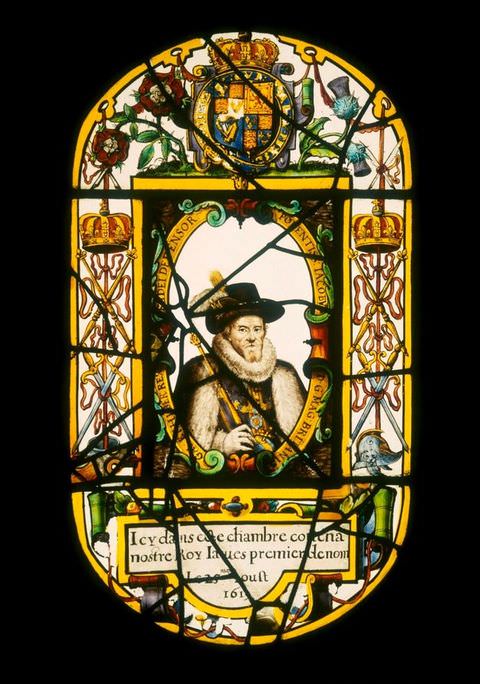

66A somewhat different example may also serve to illustrate the issue. According to John Nichols in his Progresses, Processions and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First, there was once a window at Wroxton Abbey in Oxfordshire with two painted glass panels that featured James and his favourite.67 Wroxton was the house that Sir William Pope, later earl of Downe, rebuilt over medieval priory foundations during James’s reign. Pope had commissioned elaborate painted glass from Bernard van Linge for its chapel, and some of the windows in his domestic spaces were similarly decorated. However, by the time Nichols was writing, the panels featuring James and Buckingham had been moved to a building known as the Chicken House in Hampstead, and had then joined the large collection of stained and painted glass made by Sir Thomas Neave.68 Nichols included as the frontispiece for volume 3 of his Progresses an engraving of the panels in situ at the Chicken House, which he took from John James Park’s Topography and Natural History of Hampstead, published in 1814. In the panels as illustrated by Park, the cartouche beneath the image of James contains the legend “Icy dans cette chambre coucha nostre Roy Iaques premier de nom le 25 Aoust 1619” (fig. 5). There is a small but significant change in Nichols’s frontispiece: the date has been altered to “23 Aoust 1619” to support Nichols’s assertion that James and his favourite stayed at Wroxton on the latter date, that the panels were originally at Sir William Pope’s house, and that they had been created to commemorate that visit.

67

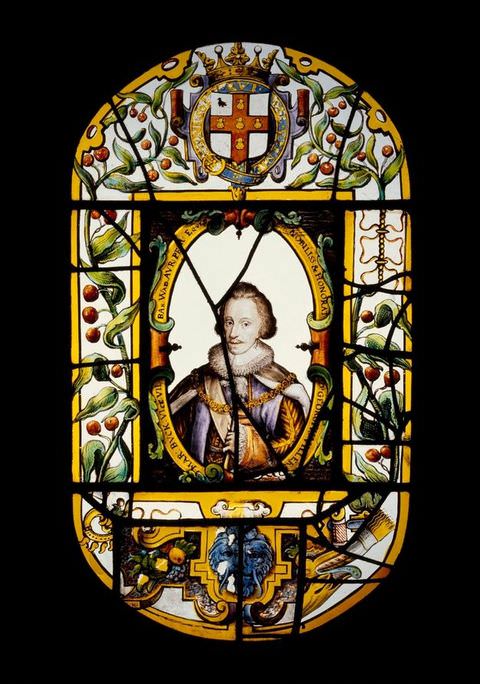

Fortunately, the panels themselves have survived; they were acquired from the Neave collection by the National Museum of Scotland (then the Royal Scottish Museum) in 1966 (figs. 6 and 7). The date on the panel of the king clearly reads “25me Aoust 1619”, though when it came into the Scottish collection a lead repair obscured the middle of the lettering. Thus, the panels’ origin and the precise date of the occasion they marked are uncertain, though Wroxton remains the likeliest candidate: as Nichols noted, John Chamberlain recorded the king’s intention to stay with Pope during the summer progress of 1619 in a letter written that June.69 The panels appear to date from the early 1620s, reproducing recently printed images of James and Villiers (figs. 8 and 9), which was when Pope was engaged in his rebuilding and commissioning painted glass for both his house and his chapel.70 This, however, is not their only mystery. In the engraving reproduced by Nichols, the two panels make an obvious pair: both James’s and Buckingham’s portraits and the decorative frames around them appear to be in their original state, although the blank cartouche below the latter may strike us as unusual. This complementarity encouraged Jonathan Goldberg to read the panels as a pairing and to suggest that “they might celebrate a marriage”.71 The idea that James and Buckingham were in some sense married has found a degree of support in modern scholarship, from Rictor Norton, David Bergeron, and Michael Young through to Gareth Russell.72 It is for the most part predicated on the language James used in one of his letters to Villiers, but such terms were also bound up with other ways in which James configured the bond between them.73 The pair of matching panels appears to be a visual confirmation, and—what’s more—one that was seemingly celebrated not by the king and Buckingham but by one of their hosts, as if any such “marriage” met with public recognition.

69

However, the picture is—literally—not so simple. A comparison of the panels and their nineteenth-century engraving shows some striking differences. The engraving suggests that the original composition has been retained, but the surviving panels are marked by multiple inconsistencies in their decorative elements, which indicate that they may have been reconstructed from a not entirely complete set of broken pieces. The base of the support to James’s left is clumsily reconstructed, while the decorative elements of the panel featuring Buckingham are much more comprehensively rearranged. And not just rearranged: at top right, and again in the border at the central portrait’s base, decorative elements have been inserted from a different panel entirely. These seem to match the proportions of the rest but clearly originate elsewhere. Of course, this may have happened after they were engraved, and the inserted elements may have come from unrelated fragmentary sources. Moreover, the busy and incoherent cartouche beneath Buckingham is another stark departure from the early nineteenth-century illustration which requires some kind of explanation. But the consonance of proportions between the incongruent framing elements and the panels themselves suggests a closer relation between them. The likeliest explanation is that there were originally more than two panels, presumably featuring at least one other member of the royal party whose 1619 visit the surviving glass images commemorate, and that the engraving represents them in a distorted idealised state. Could these inserted elements perhaps be traces of a panel featuring Prince Charles, echoing the triadic arrangement found in the iconography of the decorations at Apethorpe? On the current evidence, it is impossible to say. Nonetheless, it is clear that the exclusive pairing perceived by Goldberg is most likely illusory, and any suggestion of a marriage between the two men needs to acknowledge the complexities in the evidence that make it hard to sustain such a determinate framing. Here, as elsewhere, the apparent evidence to support claims about the truth of James’s sexual relationships speaks of something more than our demand to know the king’s supposed secret is able to hear.

The King’s Queer Style

Reading the material and textual traces of the king’s affectionate displays solely as evidence for his sexuality does not allow us to escape the dead end to which the epistemology of the royal closet leads. To chart a more fruitful course, I would like to return to that combination of behaviour and display that has often been found so troubling and that has triggered a fierce aversion to the king’s “unseemliness” in some commentators. This was a revulsion against James’s apparent display of his affections as much as against the affections themselves: as Albert Fontenay, Queen Mary’s envoy, noted in August 1584, James “loves indiscreetly and obstinately, despite the disapprobation of his subjects”, a disapprobation that has echoed down the centuries.74 The ideals of “discretion” or decorum that James breached were, of course, gendered: both contemporaries and historians have noted the king’s apparent deviations from masculine norms or ideals.75 This deviance, it would seem, lay not just in the spectre of sodomy but also in his refusal (or failure) to confine himself to a behavioural closet. Scholars such as Bergeron, Young, and Hammond have done much to reshape our valorisation of the king’s character and interpersonal behaviours, displacing the moralised disgust of centuries.76 But, in the effort to establish its truth, James’s behaviour has been read hermeneutically as a sign of homosexuality; this, in turn, has prompted scholars such as Malcolm to insist that this behaviour was simply a sign of male friendship or companionship or some other mode of non-erotic association. In both approaches, the displayed behaviour has been read through, subjected to a predetermined hermeneutic frame that takes us away from what we can actually see, when it was the behaviour’s visibility that made it so remarkable to James’s contemporaries.

74The revulsion against James’s “unseemly” conduct reaches a singular height of grotesquerie in William McElwee’s mid-twentieth-century hyperbolic extrapolation of James’s behaviour towards Carr from the account in the letter quoted above: James “appeared everywhere with his arm round Carr’s neck, constantly kissed and fondled him, lovingly feeling the texture of the expensive suits he chose and bought for him, pinching his cheeks and smoothing his hair”.77 This reflects more on McElwee and his period’s intense anxieties about homosexuality than it does on James. Bergeron rightly notes that this exaggerated portrait makes the king “a bit of a contortionist”, a man twisted out of shape by his pathological and perverse desires. However, a further look at the details highlighted—or, more properly, imagined—by McElwee clarifies the immediate source of his disgust. It is James’s bodily movements, gestures, and disposition that alarm him: the arm round the neck; the kissing, fondling, pinching, and smoothing; the royal hands “lovingly feeling” the texture of Carr’s suits. McElwee’s vivid homophobic imagination recoils in horror at the king’s performance of intimacy—the movements and gestures of the royal body around and over his favourite—intimacy that is, alarmingly, public rather than private. In interpreting this as evidence either sufficient or insufficient to determine sexuality, we risk prioritising content over form, mistaking the latter for the former, and either deliberately or accidentally refusing its real implications. To pay attention to this as display, first and foremost, we need to seek out a sense of the king’s reported and recorded corporeal behaviour as style.

77In this vein, we could usefully follow David Halperin’s proposal for “a different undertaking, … a hermeneutics of style—a hermeneutics of ‘surfaces’ that would be not suspicious but descriptive—and … recognise the potential importance of an inquiry into the content of form that would highlight the thematics, or the queer counter-thematics, of style itself”.78 In some ways, and in line with Halperin’s acknowledged debt here to Susan Sontag, this would not be a hermeneutics at all, insofar as hermeneutics is often understood as an attempt to reduce the surface of things to an underlying meaning or substance. An attention and alertness to style actually challenges modes of reading that imagine themselves as primarily interpretative. Halperin’s sense that an orientation towards style is a key element in the work of queerness is echoed by Taylor Black. For Black, style has a “naturally opaque status as a term of analysis”, a status that reorganises reading such that “analyzing style means dialing into the nature of expression in search of difference”, while “writing about style means looking and listening for those qualities that demarcate or particularize one individual from another”.79 Sexuality considered as the identitarian endpoint of interpretation is not at all the same as an erotics of the surface through which queer lives might be lived. Style is often thought of as primarily a matter of dress, as in James Bromley’s recent investigation of early modern queer style, and McElwee’s reference to “expensive suits” in his scene of debauchery certainly evokes that dimension.80 Maria Hayward has posited the existence of a “Stuart style” defined primarily as sartorial, which is itself an important suggestion. When James jumped up onto the bridal bed of Philip Herbert and Susan de Vere he was, as Hayward says, no doubt wearing one of the eighteen nightgowns he had ordered between 1603 and 1613, made from expensive, ostentatious fabrics and often lined with fur.81 The primacy of the bedchamber as a political space in James’s court would have made such garments a site for the sometimes arresting conjunction of intimacy and publicness that I have argued was key to James’s practice of kingship.82 A queer attention to style emphasises that clothing is also deportment; indeed, given that the living clothed body moves, it is always also deportment. If we were to read James’s displays of intimate affection as style in this mode, then its evidently transgressive or “unseemly” aspects may appear anew and as precisely queer, in accordance with how Bromley and many others deploy the term as a critical perspective on—and theoretical intervention in—the historical composition and apprehension of erotics. Queer style transgresses not only the norms governing the categorisation of sexuality or of the production of sexuality as a category, but also the epistemological framing that occludes this key social dimension of the erotic only, in an apparently triumphant move, to reveal sexuality as that which is fundamentally secret or interior.

78One familiar motif of James’s kingship, and one surviving object, may serve to make a case for reading his conduct and disposition as style in this way. Infuriated by resistance to a plan to marry the daughter of Sir Edward Coke to Buckingham’s elder brother, the king called the Privy Council to Hampton Court after his return from Scotland in 1617; his words on this occasion were reported by Gondomar, the Spanish ambassador, in a well-known diplomatic letter:

83Pausing briefly, the King continued, saying he wanted to make it clear that he was neither God nor angel but a man, a man like others, and as such, acted like a man. He confessed his preference for what he loved, even above other men. He declared his affection for the Earl of Buckingham surpassed that for anyone present, but he saw no fault in this since even Christ had done the same, and thus, he could not be reproached. Concluding this part of his speech, he asserted that just as Christ had His John, he had his George.83

This declaration has been cited as evidence for the hidden truth of James’s relationship with Buckingham, and even of their supposed marriage. In the Gospel of John, the ostensible author is repeatedly described as the disciple “whom Jesus loved”, and it is this sense of affective intimacy that James is evoking here.84 Rictor Norton was, it appears, the first modern scholar to suggest that James may have been referring here to the blasphemous idea that Christ and the disciple whom he loved had a sexual relationship, a suggestion taken up by Young.85 Malcolm, by contrast, calls this “a rare lapse of judgement” on Norton’s part, insisting that “it is inconceivable that James, a pious theologian, would have intended such an implication”, though the notion of the relationship between Jesus and John as a marriage of sorts was broached by at least one medieval commentator.86 Certainly, the king had no difficulty speaking of his favourite as his disciple in more public forums. In a speech read by the Lord Keeper before Parliament in March 1624, the king defended his demonstrated affection for Buckingham in just these terms, describing him as “my disciple and scholler” and declaring: “I trust the Reporte not the worse which he made, because it is approved by you all: yet I beleeve an honest man, as much as all the world: and the rather because he was a disciple of mine”.87

84Such a declaration was less affectively charged than the 1617 speech before the Privy Council reported by Gondomar, but not all such invocations of the comparison are as unimpassioned. In a notorious open letter to Buckingham of 1620, the authorship of which was claimed—to his considerable detriment—by Thomas Alured, the Johannine likeness was developed at length in a way that strongly echoed James’s 1617 declaration.88 “Every person is left to affect as he likes”, the letter avers, and “neither can affection be forced”:

8889Now to disallow or confine that to a king which is left at liberty in the meanest Subject, were preposterous and iniurious. For though they command nations as they are kings: yett are they subject to their passions as they are men: and if I may alleage it without misinterpretation of others as I am free from ill meaning my selfe; who knows but (Christ the rather to shew himself a Natural Man) expressed so much the more his passion in his often weepeing, and his affections to divers particulars. But especially St. John, if I may not say his favourite, certaine the disciple whome Jesus loued more then any of the rest.89

The practice of favouritism here claims divine and natural sanction, as a form naturally taken by the distribution of affections, and kings are thereby justified in following Christ’s own, all too human, example.

There is, however, something about the letter writer’s keenness to disavow “ill meaning” that gives us pause. It sounds as though a less praiseworthy account of the passions here evoked may be available, even if the writer is not going to evoke it. The iconography associated with John the Evangelist could carry “ill meaning”: the image of John, often represented as a beardless, even effeminate, young man and associated with the eagle, may recall that of the rather less Christian figure of Ganymede.90 But, even without such implications, a dimension of the love between Jesus and John seems to have been important to James, and has queer implications in the stylistic sense I am pursuing. While John is repeatedly described as the disciple whom Jesus loved, this love is vividly embodied at one key point in chapter 13 of the gospel narrative, where the Last Supper is described. Indeed, we could say that it strikes a pose. Verse 23 includes the seemingly tangential detail that “there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved”, a compositional moment unique to this version of the narrative. The bond between Jesus and John is here evident in and as bodily disposition, or style.

90

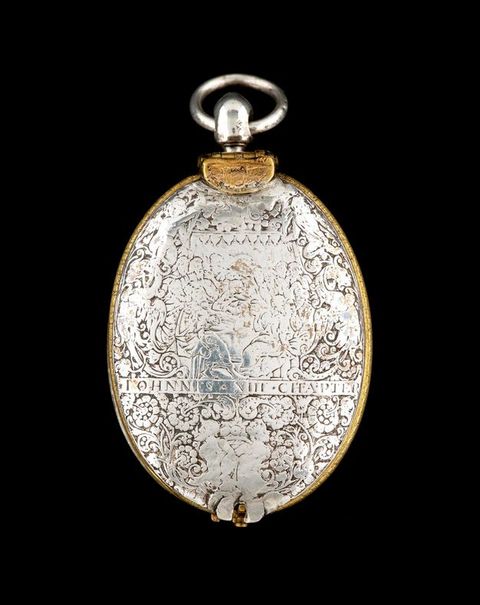

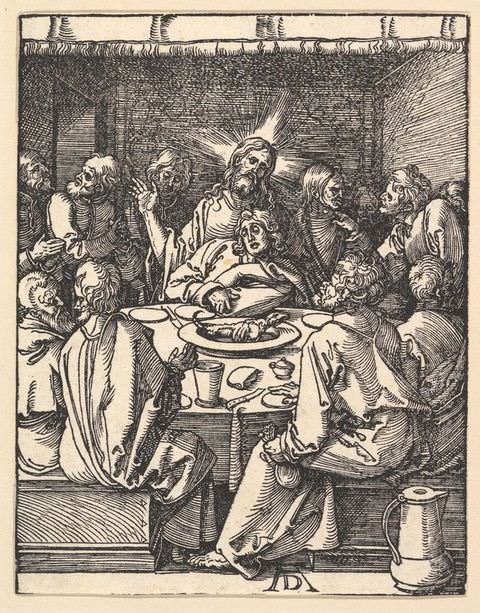

That this mattered to James is evident from a watch apparently given by the king to his earlier favourite, Robert Carr, earl of Somerset, which has not previously been the focus of much critical attention.91 This watch, made by the royal watchmaker, David Ramsay, is now also in the collections of the National Museum of Scotland.92 It would be reasonable to assume that it was presented to Carr by James either on his elevation to the earldom in November 1613 or on his marriage to Frances Howard the following month, though this cannot be determined with certainty. The inner faces of its casing feature a representation of James and Anna on one, and the Somerset coat of arms on the other. The outer faces feature two scenes from chapter 13 of John’s Gospel, the first of which shows Christ washing the disciples’ feet. The second depicts the Last Supper itself and, although it is somewhat worn, enough definition survives to show that at its focus is Jesus with John resting on his bosom, exactly as the verse says (fig. 10). While it is not by any means an exact copy, the composition recalls Albrecht Dürer’s well-known rendering of the same scene in one of the plates from his Small Passion (fig. 11). In Dürer’s depiction, the haloed Christ sits upright, with his right hand raised and his left arm wrapped protectively round his beloved disciple. John rests soporifically, safe in the embrace of his master, his eyes closed. The watch echoes this arrangement, with Christ as king sat at the head of the table and John again held secure in the protective embrace of his master. This is without doubt a demonstration of favour and of the love between a master and his disciple; insofar as it translates analogically to James and Carr, as it is clearly intended to do, it depicts the Last Supper not as a private gathering but as a more public dinner, with the other disciples cast as a courtly audience. Crucially, in this context it renders love as visible style: the intimate relationship between the two men exists in the way their bodies are entwined in full view of all those present. There is no mystery here and no secret. Jesus loved John, as James loves his favourite: the scandalmongers show only their own moral and intellectual turpitude by presuming that this disposition should be consigned in shame to the tiring house or royal closet and interpreted accordingly. That it is on show in its undeniable physicality, and that it can be crystallised into a memorable image echoing that of Dürer’s widely circulated engraving, are precisely the challenge of the king’s queer style: showing everything, concealing nothing, and defying anyone—then or now—to call it unseemly.

91

Acknowledgements

I wish to record my deep gratitude to my dear friend and colleague Catriona Murray, whose expertise and suggestions have been invaluable to me in writing this article.

About the author

-

James Loxley is Professor of Early Modern Literature at the University of Edinburgh. They are the author of several books on early modern literature and culture, including Royalism and Poetry in the English Civil Wars (Palgrave Macmillan, 1997), Ben Jonson (Routledge, 2002), and Ben Jonson’s Walk to Scotland (with Anna Groundwater and Julie Sanders; Cambridge University Press, 2015). They have published numerous articles and essays on the poetry and drama of the early modern period, with a particular focus on Jonson, Andrew Marvell, Katherine Philips, and Thomas Hobbes.

Footnotes

-

1

Benjamin Woolley, The King’s Assassin: The Fatal Affair of George Villiers and James I (London: Pan Macmillan, 2017). ↩︎

-

2

Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller, Bad Gays: A Homosexual History (London: Verso, 2022), 5. ↩︎

-

3

Lucy Hughes-Hallett, The Scapegoat: The Brilliant Brief Life of the Duke of Buckingham (London: 4th Estate, 2024); Gareth Russell, Queen James: The Life and Loves of Britain’s First King (London: William Collins, 2025). ↩︎

-

4

Michael Young, James VI and I and the History of Homosexuality (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000); David Bergeron, King James and Letters of Homoerotic Desire (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1999), 179. Bergeron explores the topic further in “Writing King James’s Sexuality”, in Royal Subjects: Essays on the Writings of James VI and I, ed. Daniel Fischlin and Mark Fortier (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2002), 344–68. ↩︎

-

5

Michael Young, “James VI and I: Time for a Reconsideration?”, Journal of British Studies, 51 (2012): 566. His reference is to Alan Bray, “Homosexuality and the Signs of Male Friendship in Elizabethan England”, History Workshop Journal 29 (1990): 1–19. ↩︎

-

6

See Noel Malcolm, Forbidden Desire in Early Modern Europe: Male–Male Sexual Relations, 1400–1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024), 273–76. Bray’s 1990 essay, “Homosexuality and the Signs of Male Friendship”, was the basis for his The Friend (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). In addition to the influence of Bray, there is a certain irony in Young blaming the “queer theory” influential in literary studies for the new reluctance to interpret James’s behaviour as firmly indicative of sexual relationships (“James VI and I”, 566), while Malcolm claims that Young’s own interpretations of the evidence are typical of “a style of argumentation encountered more often among those who write about sodomy in literary history” (Forbidden Desire, 276). ↩︎

-

7

Michael Corrie Questier, “The Reputation of James VI and I Revisited”, JBS: Journal of British Studies 61 (2022): 968. ↩︎

-

8

Kathryn Morrison, ed., Apethorpe: The Story of an English Country House (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 89–93. ↩︎

-

9

Morrison, Apethorpe, 114–39. ↩︎

-

10

Morrison, Apethorpe, 143. ↩︎

-

11

Morrison, Apethorpe, 163–65, 414. ↩︎

-

12

Morrison, Apethorpe, 164. ↩︎

-

13

Morrison, Apethorpe, 159–60. Buckingham’s personal badge as Lord High Admiral was an anchor fouled by a chain or rope; Morrison suggest that this one, unfouled, may be the badge of the Navy Board instead. While the coronet is closest in design to that of a duke, they also point out that the ranking of coronets was not fully formalised at this date. ↩︎

-

14

Maev Kennedy, “Restoration Opens Doors on a Royal Scandal after 400 Years”, Guardian, 4 August 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/aug/04/artnews.monarchy. ↩︎

-

15

Morrison, Apethorpe, 164. ↩︎

-

16

Hilary Clydesdale, “Secrecy, Surveillance and Counterintelligence in the Prose Fiction of Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson”, PhD thesis (University of Edinburgh, 2024). ↩︎

-

17

Walter Scott, ed., The Secret History of the Court of James the First, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: John Ballantyne, 1811), vol. 1, “Advertisement”. See also Clydesdale, “Secrecy”, 138–40. ↩︎

-

18

Rebecca Bullard, “Introduction: Reconsidering Secret History”, in The Secret History in Literature, 1660–1820, ed. Rebecca Bullard and Rachel Carnell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 2–3. ↩︎

-

19

Alastair Bellany and Thomas Cogswell, The Murder of King James I (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015). ↩︎

-

20

Corona Regia, ed. and trans. Tyler Fyotek and Winfried Schleiner (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 2010), 35. ↩︎

-

21

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 73. ↩︎

-

22

Sedgwick, Epistemology, 74. ↩︎

-

23

David Halperin, How to Do the History of Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 27–32; Valerie Traub, Thinking Sex with the Early Moderns (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 57–81; Bruce Smith, Homosexual Desire in Shakespeare’s England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); Sedgwick, Epistemology, 74. ↩︎

-

24

Malcolm, Forbidden Desire, 119–21. ↩︎

-

25

Philip Stubbes, The Anatomie of Abuses (London, 1583), sig. L8v. ↩︎

-

26

James Bromley, Intimacy and Sexuality in the Age of Shakespeare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 1. ↩︎

-

27

Danielle Clarke, “‘The Sovereign’s Vice Begets the Subject’s Error’: The Duke of Buckingham, Sodomy, and Narratives of Edward II”, in Sodomy in Early Modern Europe, ed. Tom Betteridge (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 46–64. ↩︎

-

28

Francis Osborne, Historical Memoires of the Reigns of Queen Elizabeth, and King James (London, 1658), 128. ↩︎

-

29

Anthony Weldon (attrib.), The Court and Character of King James (London, 1650), 177. ↩︎

-

30

King James VI and I, Political Writings, ed. Johann Somerville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 3. I have modernised u, v, j, and i in quotations. ↩︎

-

31

James VI and I, Political Writings, 4–5. ↩︎

-

32

James VI and I, Political Writings, 184, 179. ↩︎

-

33

James VI and I, Political Writings, 251. ↩︎

-

34

The National Archives, Kew, SP 53/13 fol. 107. The Hilliard miniature appears to have been adapted from the Simon de Passe engraving of James that was printed in Compton Holland and Henry Holland, Bazilologia: A Booke of Kings (London, 1618). ↩︎

-

35

See, for example, Curtis Perry, Literature and Favoritism in Early Modern England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Mario DiGangi, The Homoerotics of Early Modern Drama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 100–33; and Mario DiGangi, Sexual Types: Embodiment, Agency, and Dramatic Character from Shakespeare to Shirley (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 192–220. ↩︎

-

36

“The King was the Fountain of Honour indeed, but there was a pre-eminent Pipe, through which all Graces flowing from him were derived. I pray the Reader to consider the sweetness of this King’s Nature, (for I ascribe it to that cause) that from the time he was 14 Years old and no more, that is, when the Lord Aubigny came into Scotland out of France to visit him, even then he began, and with that Noble Personage, to clasp some one Gratioso in the Embraces of his great Love, above all others, who was unto him as a Parelius; that is, when the Sun finds a Cloud so fit to be illustrated by his Beams, that it looks almost like another Sun”. John Hacket, Scrinia Reserata: A Memorial Offer’d to the Great Deservings of John Williams (London, 1693), 39. For James’s organisation of the chamber in Scotland, see Amy Juhala, “‘For the King Favours Them Very Strangely’: The Rise of James VI’s Chamber, 1580–1603”, in James VI and Noble Power in Scotland 1578–1603, ed. Miles Kerr-Peterson and Steven Reid (London: Routledge, 2019), 155–69. ↩︎

-

37

Steven Reid, The Early Life of James VI and I: A Long Apprenticeship (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023), 121–51. ↩︎

-

38

See Neil Cuddy, “The King’s Chambers: The Bedchamber of James I in Administration and Politics, 1603–1625” (DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 1987); and Linda Levy Peck, “Monopolizing Favour: Structures of Power in the Early Seventeenth-Century English Court”, in The World of the Favourite, ed. J. H. Elliott and L. W. B. Brockliss (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999), 54–70. ↩︎

-

39

See, for example, the notes from Anna to Buckingham highlighted by Leeds Barroll, which approvingly echo the imagery of master and dog evident in the correspondence between James and Buckingham. Leeds Barroll, Anna of Denmark, Queen of England: A Cultural Biography (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 212. ↩︎

-

40

Christiane Hille, Visions of the Courtly Body: The Patronage of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham, and the Triumph of Painting at the Stuart Court (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2012), 103. ↩︎

-

41

Joseph Bain, ed., Calendar of Border Papers, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: H. M. General Register House, 1894–96), 1:82. ↩︎

-

42

The Letters and Epigrams of Sir John Harington, ed. Norman McClure (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1930), 32. ↩︎

-

43

The Diary of Sir Simonds D’Ewes, ed. Elisabeth Bourchier (Paris: Didier, 1974), 57. ↩︎

-

44

Russell, Queen James, 338. ↩︎

-

45

D’Ewes, Diary, 92–93. ↩︎

-

46

Historical Manuscripts Commission, Manuscripts of the Marquess of Downshire, vol. 6 (London: HMSO, 1995), 85. ↩︎

-

47

David Calderwood, The History of the Kirk of Scotland, ed. Thomas Thomson and David Laing, 8 vols. (Edinburgh: Wodrow Society, 1842–49), 5:171. ↩︎

-

48

Alastair Bellany and Andrew McRae, eds., Early Stuart Libels: An Edition of Poetry from Manuscript Sources, Early Modern Literary Studies, Text Series I, 2005, Nvi1, https://www.earlystuartlibels.net/htdocs/index.html. See also Curtis Perry, “‘If Proclamations Will Not Serve’: The Late Manuscript Poetry of James I and the Culture of Libel”, in Royal Subjects, ed. Fischlin and Fortier, 205–32. ↩︎

-

49

Perry, “‘If Proclamations Will Not Serve’”, 215. ↩︎

-

50

“King James on the Blazeing Starr: Octo: 28: 1618”, in Bellany and McRae, eds., Early Stuart Libels, Ni1. ↩︎

-

51

William Harris, An Historical and Critical Account of the Life and Writings of James the First (London, 1753), 73, cited in Bergeron, Letters, 33. ↩︎

-

52

Reid, Early Life of James VI, 122. See also Joseph Bain et al., eds., Calendar of State Papers, Scotland, 11 vols. (Edinburgh, 1989–36), 5:610; and Young, James VI and I, 39–42. ↩︎

-

53

Young, James VI and I, 40. ↩︎

-

54

Bain et al., Calendar of State Papers, Scotland, 6:149. ↩︎

-

55

Bain, Calendar of Border Papers, 1:83. ↩︎

-

56

Reid, James VI and I, 167. ↩︎

-

57

Calderwood, History, 3:658. ↩︎

-

58

Calderwood, History, 3:658. ↩︎

-

59

Calderwood, History, 3:642. ↩︎

-

60

Young, James VI and I, 40–42. ↩︎

-

61

Osborne, Historical Memoires, 55 (emphasis original). ↩︎

-

62

Osborne, Historical Memoires, 55. ↩︎

-

63

Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 1603–1624: Jacobean Letters, ed. Maurice Lee (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1972), 54. Carleton’s letter is dated 15 January 1604. Cf. Paul Hammond, Figuring Sex Between Men from Shakespeare to Rochester (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 128, citing the transcription in E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage, 4 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1923), 3:279. ↩︎

-

64

Hammond states that the marriage took place “four years later”, but this is an error. Hammond, Figuring Sex, 129. Scott’s source is Esmund Sawyer, ed., Memorials of Affairs of State in the Reigns of Q. Elizabeth and K. James I … from the Original Papers of … Sir Ralph Winwood, 3 vols. (London, 1725), 2:43. Carleton sent a very similar account using the same key descriptions of the king’s behaviour to John Chamberlain: see Dudley Carleton, 66. ↩︎

-

65