“Certane Picturis of His Majesties Visage”

“Certane Picturis of His Majesties Visage”: Tracing James VI’s Succession Campaign through Visual and Material Display and Dissemination

By Kate Anderson

Abstract

In the final decades of the sixteenth century, King James VI of Scotland (later King James I of England and Ireland), with the support of his queen, Anna of Denmark, engaged in a rich programme of patronage and visual and material display that centred the themes of dynasty, unity, and Protestantism to promote and bolster James’s claim as Elizabeth I’s successor. This royal patronage of Scottish and European émigré artists saw the production, dissemination, and presentation of art, print, and luxury objects both at home and abroad. However, James and Anna’s cultural programme has been overlooked, and no study to date has taken an overview of the output of the artistic activity that flourished in Scotland during this crucial period, when the question of the succession was at the heart of Scottish, English, and Irish politics. The article seeks to address this gap and brings together portraits, prints, jewellery, coins, and medallions dating from the years between about 1580 and 1604 to analyse the iconography and messaging devised during James’s succession campaign. It also demonstrates how interconnected these art forms were and sheds light on the unique network of Edinburgh-based artists and makers working for the king and court in the late sixteenth century.

Introduction

The rich visual and material world of King James VI of Scotland, later King James I of England and Ireland, is rarely examined, and the artists whom he commissioned are often labelled by art historians as unskilled or provincial. Too often the cultural output of this period is subsumed into Elizabethan or post-1603 “Stuart” studies of Jacobean art, or even at times completely overlooked. To date, no study has attempted to analyse or take an overview of the programme of artistic activity by both Scottish-born and émigré artists working in Edinburgh and the surrounding royal burghs during these crucial years when the question of Elizabeth I’s successor was at the centre of Scottish, English, and Irish politics.

In his seminal Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, Roy Strong claims that “the iconography for James I is, for most part an unsatisfactory one, due to both the King’s personal dislike for sitting for his picture and to the decline in standards of production of royal portraits during his reign”.1 Indeed, Strong’s section on pre-1603 portraiture is limited to fifteen lines and frequently quotes from The Court and Character of King James I, the xenophobic account attributed to the dismissed English courtier Sir Anthony Weldon, which was published posthumously during the Interregnum.2 Weldon’s account has been used as a source by historians and art historians for centuries and is still quoted today, distorting the facts, damaging James’s reputation, and influencing scholarly opinion. While the claims surrounding the king’s feelings on portrait sittings cannot be substantiated, what is indisputable is that, from an early age, he and his councillors engaged in the patronage, dissemination, and presentation of royal portraiture in a variety of media.

1For clarity this article centres on an examination of painted portraits but, unlike some studies concerned with Jacobean art, it does not look at paintings in isolation but instead takes a broader, object-centred methodology, reinforced by archival evidence, to consider the portraits alongside jewellery, coins, medals, and printed works produced in these years. It should be noted that, while dress and textiles are extremely relevant and are briefly discussed, they are not a primary focus, to avoid duplication with other articles in this issue. Another significant aspect of material and visual display during this period that is not fully examined in the article because of the limits of space is decorative painting including the heraldry, arms, and devices found in royal and civil architectural schemes. Michael Bath’s authoritative work on Renaissance decorative painting in Scotland emphasises the central role that decorative, heraldic, and emblematic painting played in sixteenth-century Scottish built and spatial environments.3 Robert Tittler’s extensive and invaluable directory on early modern British painters collates the names and activities of Scottish, English, and émigré painters, heralds, painter-stainers, limners, and journeymen, and demonstrates the extensive network of artists and craftspeople working across these genres during James’s reign.4

3While not strictly chronological, the article takes a thematic approach based on media and the interconnected nature of the visual and material world, and broadly considers the period of the mid-1570s to around 1604, with an emphasis on the 1590s. It seeks to demonstrate that James, in collaboration with his queen, Anna of Denmark, consistently engaged with and contributed to a rich programme of patronage and display, which communicated messages around dynasty, legacy, and union, and promoted the king of Scots as the English queen’s successor.

The article’s focus is on the Flemish émigré artist Adrian Vanson, who was employed at the Scottish court as James’s official painter in the 1580s and 1590s, and focuses on a group of three previously unpublished painted portraits, which it attributes to Vanson.5 It situates Vanson in his Scottish context and uncovers the network of Scottish and émigré artists, craftspeople, and goldsmiths who were working in the city of Edinburgh and who were patronised by Crown and court.

5Any study of early modern visual and material cultural faces the challenge of the absence of extant material. However, by combining object-based analysis of surviving artworks with a study of archival records from the period, we can enhance our understanding of the extent of the expenditure on luxury goods and artistic commissions, which gives us new insight into James and Anna’s artistic engagement in Scotland.6 Before we do so, we should set the context of the political and cultural landscape of the country in the mid-sixteenth century.

6Mary, Queen of Scots

On 19 June 1566 Mary, Queen of Scots, gave birth to a son, her only child and heir, Prince James Charles Stuart, at Edinburgh Castle. The decades of the 1560s and 1570s saw political upheaval and religious strife, triggered by the Protestant Reformation, which took place in Scotland in 1560. On Mary’s return to Scotland from France in 1561, she refused to ratify the reform, and this resulted in feuding between noble factions, power struggles for the position of regent, and a sequence of catastrophic events, including the murder of James’s father, Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, and ultimately Mary’s forced abdication in 1567. The volatile environment and the absence of a reigning monarch and a settled royal court meant that opportunities for artistic patronage during James VI’s minority were scarce. Native-born craftspeople were operating in Edinburgh alongside a handful of émigré painters who had arrived in the city, but royal commissions were limited.

While there is very little surviving Scottish material from these years, archival records give us a glimpse into the type of art and objects that were produced. As early as 1570, when James was only four years old, there is a record of an emblematic jewel with iconography and messaging promoting the idea of a Scottish succession.7 When the jewel was discovered by the English ambassador Thomas Randolph, he immediately had it sent to England. The jewel’s imagery was described as featuring two lions fighting before an enthroned woman and entwined thistles and roses, with the motto “Fall what may Fall the Lion shall be Lord of All”. Could the jewel have been commissioned by Mary herself or by one of her close supporters? While we know nothing of the jewel’s maker or what become of it, the episode illustrates the potency that jewellery had in communicating political ambitions, in this case Mary’s positioning as Elizabeth’s successor.

7It was through Mary’s gifts, letters, and political manoeuvring that the young James, despite having been separated from his mother as an infant, learned the currency of visual imagery and material display. Mary’s recently decoded cipher letters reveal that in October 1582 she wrote to the French ambassador Michel de Castelnau about a new portrait type of James that he had sent her.8 Around the same time, portraits were commissioned by James and his councillors to send to European royal houses as part of the king’s marriage negotiations. A precept in the Scottish Treasurer’s Accounts relating to the royal painter Arnold Bronckorst, dated 19 September 1581 records payments for two portraits, one costing £30 Scots which was to be “carried to a Princess of S___d__” (possibly Sweden).9

8Indeed, during her imprisonment, throughout the 1580s, Mary requested portraits of James. In April 1586, just a few months before her arrest, she wrote to the French ambassador Charles de Prunelé, Baron d’Esneval, who was visiting James at Falkland Palace at the time, to request that he procure a full-length portrait of the king taken from life, “Je vous prie me recouvrer de mon filz ung sien pourtraict en grand, faict sur sa personne propre” (I beg of you, recover from my son a life-size portrait of him made from life).10 James instructed that a full-length copy of a recent portrait be made by a painter who appears to have been in demand as there was, “n’est retrouvir que luy en tout Lyslebourg” (no other such to be found in all of Edinburgh).11 Throughout her imprisonment Mary consistently enquired about her son’s health, well-being and progress, and it was through the medium of portraiture that she found reassurance and connection.

10In July of the same year, correspondence between Catherine de’ Medici and D’Esneval concerning the marriage negotiations was sent, in which the queen sought an update on the proposal of her god-daughter Catherine, princess of Navarre, as a bride for James.12 D’Esneval sent a reply explaining that a copy of a portrait of the king would first be sent to Denmark–Norway for consideration by Princess Elisabeth, Anna’s elder sister, who had been initially proposed as a potential bride for James.13

12While portraits were an important tool in brokering advantageous unions, they were also used to promote political aspirations, as demonstrated by the sophisticated use of imagery by Mary. When James reached his majority, Mary and her supporters, headed by John Leslie, bishop of Ross, devised a constitutional arrangement known as the “Association”, which proposed that Mary return to Scotland to share sovereignty with James and rule jointly with him.14 To promote their cause, they circulated various images that saw mother and son united despite their physical separation. A double portrait by an unknown artist positions Mary and James side by side, with the imperial Scottish crown and the date 1583 between them, symbolising joint sovereignty (fig. 1).

14

Their portraits were copied from existing individual paintings and then combined to create a distinctive double portrait. This visual imagining of the “Queen and King of Scotland”, as they were to be titled, demonstrates how Mary exploited images, and specifically portraiture, as a political tool. The young King James learnt first-hand how art could be deployed as propaganda. Considered together, this archival evidence and surviving portraits reveal the pivotal and varied role that visual imagery played in Mary’s final and James’s formative years.

Adrian Vanson and Artistic Networks in Edinburgh

The artist most closely associated with the king and court during James’s Scottish reign was Adrian Vanson. Vanson was born in Breda and was one of many Protestant Netherlanders who fled their home to escape religious persecution.15 Taking advantage of the flourishing trade links between Scotland and the Low Countries, many of these émigré artists and craftspeople settled with their families in Scotland to pursue careers in the capital. Prior to Vanson, the first reference to a Netherlandish artist working for the Crown was a payment to Arnold Bronckorst recorded in Scottish Treasures Accounts in April 1580.16 Bronckorst had arrived in Scotland from London as an agent of Nicholas Hilliard and in the company of the artist Cornelius de Vos, who had travelled to the country as part of a gold speculating venture.17 While Hilliard and De Vos returned to England, Bronckorst appears to have been pressurised, probably by the then regent, James Douglas, earl of Morton, to stay in Scotland to work as a court painter, where he was charged with making “all the small and great pictures for his majesty” and received a yearly pension from the king.18 There was certainly crossover between Bronckorst and Vanson, for both names are recorded in sums paid from the Treasury to them in 1580 and 1581. It’s likely that Vanson had also come to Scotland via London, and he may have become aware of Bronckorst’s predicament through his connection with the Netherlandish artist community in the city. Another possibility is that Vanson was the painter referred to as “Lord Seton’s painter”, and it was George Seton, seventh Lord Seton who introduced him to Scotland.19 In 1582 Vanson was recorded as “a stranger in the parish of St Nicholas Acons in Langborne ward, London”.20 In the following year Bronckorst departed Scotland, leaving his post vacant, and Vanson took the opportunity to seek royal patronage north of the border.21 By 1584 Vanson had been appointed James VI’s official court painter, and in 1585 he was made a burgess of the city of Edinburgh.22

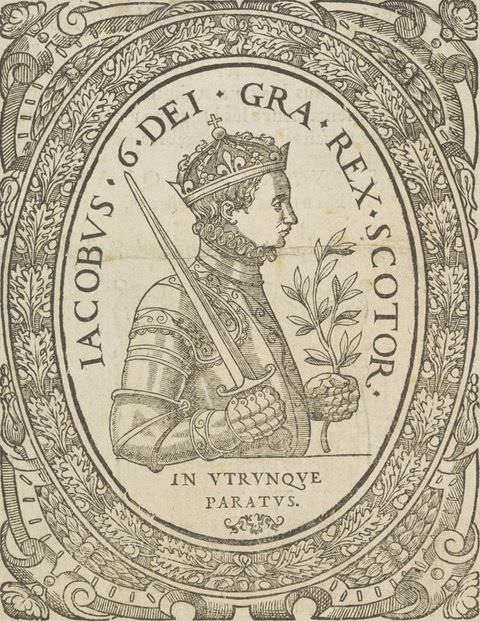

15The first archival record linking Vanson to Scotland is dated 1581, which shows that “Van Soun”, as he signed his name, was paid £8 10s. Scots for two royal portraits; these were sent to Geneva in 1579 to act as sources for plates to illustrate Theodore Beza’s Icones, id est verae imagines virorum doctrina simul et pietate illvstrium (1580).23 There is no record of the identity of the sitters in the portraits, but a letter written by James’s tutor Sir Peter Young, sent to Beza on 13 November 1579, refers to portraits by an unspecified painter of the humanist scholar and James’s tutor George Buchanan and the Protestant theologian John Knox.24 These portraits arrived too late to be made into woodcuts for the 1580 edition, but a woodcut of James VI, possibly derived from a design by Vanson, appears as the frontispiece in the 1580 edition, a fitting inclusion as Beza’s book was dedicated to the Scottish king (fig. 2). A woodcut of Knox, again probably derived from the earlier portrait sent by Vanson, features in Simon Goulart’s 1581 French edition of Icones.25

23

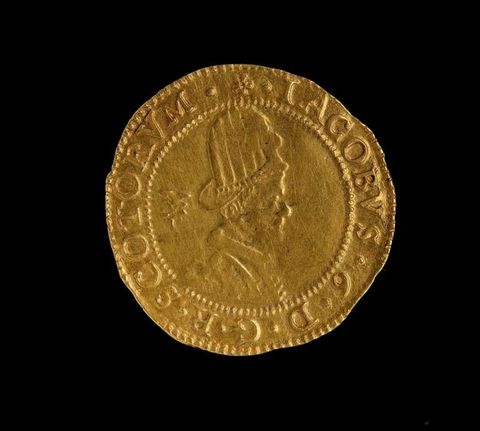

The portrait pattern for the Beza woodcut of James undoubtedly derives from one of the largest and most valuable coins produced during the king’s Scottish reign, the twenty-pound piece, a coin first minted in Edinburgh in 1575 (fig. 3). The stylistic and iconographic parallels between the woodcut and the coin are clear. The obverse of the coin features a profile portrait of James wearing armour. In his right hand he holds a sword, representing war, and in his left hand a palm leaf, representing peace, with the Latin inscription “IN. VTRVNQVE· PARATVS”, which translates as “Prepared for Either”. The woodcut shows James in the same pose, with exactly the same motto.

While the identity of the artist associated with the design of the twenty-pound piece is currently not known, the relationship between these two objects provides us with a glimpse into the network of native-born and émigré artisans—painters, goldsmiths, and printmakers—who were working and collaborating in late sixteenth-century Edinburgh. A kinsman, or possibly even a brother, of Vanson called Abraham Vanson is recorded as working in the city at this date. Abraham married Jonet Gilbert, sister of the goldsmith and financier Martin Gilbert.26 One of Gilbert’s apprentices, Thomas Foulis, became a leading goldsmith and royal financier, and also worked as a sinker, producing dies for coins at the Royal Mint. Artists including Vanson and “Lord Seton’s painter” (who may be one and the same individual) were employed by the mint to design these coin dies. Between 1581 and 1582, two payments in the Treasurer’s Account were made to “my Lord Seytonis painter for certane picturis of his majesties visage drawin by him and gevin to the sinkare to be gravin in the new cunze”.27 The sinker in this instance was Foulis.28 Significantly, not only was Foulis a goldsmith and businessman but he also held a diplomatic position at court. He was responsible for collecting James’s subsidy payments from Elizabeth I and travelled frequently between Edinburgh and London.29

26These artists and makers shared connections not only through their craft but also through marital ties and spatially within the city—they lived and worked in close proximity to each other in the dwellings, workshops, and retail premises of the Canongate area of Edinburgh. They enjoyed close links to James and the royal household, and were politically and economically important, with the goldsmiths providing a unique service as royal cash creditors.30 Vanson was at the heart of this community, yet despite his living and working in Scotland for over twenty years, a relatively small group of surviving works (only around ten) are currently attributed to him.31

30The portrait of Sir John Maitland, first Baron Maitland of Thirlestane and Lord Chancellor of Scotland, dated 1589, in the collection at Ham House, National Trust (NT 1139943), is considered to be Vanson’s touchstone painting. A group of portraits of James and Anna, dated to 1595 and attributed to Vanson, are in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland and will be discussed later in the article.32 Various other portraits have been associated with Vanson, but in recent years results from technical analysis examining the painter’s technique and materials have challenged some of these traditional attributions.33 Portraits of James in his teens and early twenties that were traditionally ascribed to Vanson include the three-quarter-length portrait of the teenage king in an orange slashed doublet in the collection of Historic Environment Scotland and on display at Edinburgh Castle, and purported to have been a portrait sent to Denmark as part of the marriage negotiations. A related but less accomplished three-quarter-length depiction of James in the collection of Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries is inscribed with the year 1583 and age seventeen. A bust-length portrait of James in an ochre-coloured doublet and large standing ruff, inscribed with the date 1586 and age twenty, is in the collection of the National Trust for Scotland and on display at Falkland Palace (fig. 4). In terms of attribution, it is the latter that shows stylistic qualities most consistent with the hand of Vanson.34

32

Three Portraits of the King of Scots

While the teenage portraits are intriguing and deserve analysis, this section focuses on a small group of related portraits of the king, which have previously been overlooked in scholarship. Painted at a key juncture in James’s life, in the years immediately following his marriage to Anna of Denmark, the three extant portraits, painted in 1591 and 1592, are inscribed with the king’s ages: twenty-four, twenty-five, and twenty-six respectively. I suggest that, stylistically and chronologically, all three portraits can be attributed to Vanson and his studio. The earliest of them, which bears the inscription 1591, is currently untraced but was last recorded in the mid-twentieth century at Castle Fraser, Aberdeenshire, where it was part of a set that also included portraits of James III, James V, and Mary, Queen of Scots (fig. 5).35

35

The second portrait, also dated 1591 but depicting James aged twenty-five, is in the collection of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Hessen Kassel Heritage, in Dresden (fig. 6). According to the online collection record, this painting may be a copy. However, following an enquiry to the curator at Hessen Kassel Heritage, it became apparent that there is some evidence to indicate that the painting may already have been in Kassel in the early seventeenth century, suggesting that it is an original work or a very early copy.36 The portrait’s early German provenance is intriguing, as five of Anna’s siblings had married into German royal houses. Within this context the marriage of Anna’s younger sister Princess Augusta is of most consequence, for she married John Adolf, duke of Holstein-Gottorp, the son of Christine of Hessen Kassel. To date this link has not been made, but I would argue that this is very strong evidence that situates the portrait in its historical context.

36

The third portrait, dated 1592, is also in Germany, in the collection of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen in Munich (fig. 7).37 This painting has an extraordinary provenance that allows us to trace its location back to 1598, when it was first recorded in Johann Baptist Fickler’s inventory of the Herzogliche Kunstkammer, Munich (no. 3042).38 The inventory reveals that the portrait was originally part of a larger set of eight, with those surviving today split across two collections in Munich. Currently the portraits of James II, James III, James IV, James V, and Mary, Queen of Scots, are in the collection of Wittelsbacher Ausgleichsfonds. It also records that the set had included paintings of James I and Anna of Denmark, both now unlocated. The Herzogliche Kunstkammer was an exceptional Renaissance collection established by Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria and later extended under his son Wilhelm V. Given the date of 1592 inscribed on the portrait, it is very likely that the portrait set entered the Kunstkammer during Wilhelm V’s reign. The early provenance of both portraits of James attests that they were sent to Germany as diplomatic gifts, where they entered princely art collections, evidencing the production, dissemination, and display of portraits of the king of Scots, individually and as part of dynastic portraits sets, to be viewed by European audiences in the late sixteenth century.

37

Portrait exchange within and between elite and royal families was a long-standing tradition and was employed for both intimate and practical purposes. Naturally, parents and siblings were keen to view likenesses of their kin who resided abroad, to assess their health and fecundity and to be reminded of absent loved ones. Furthermore, collections of family and royal portraits were displayed in picture galleries and state rooms to demonstrate natal ties and to promote the families’ dynastic links with other noble houses. A letter dated 1597 and written by Anna’s brother Christian IV of Denmark–Norway to James is evidence of this culture of familial portrait exchange. Christian wrote to his brother-in-law to request that James send full-length portraits of himself “and the Queen, your wife, our sister” to hang in his palace.39

39The survival of this group of closely related portraits of the king of Scots, painted over three consecutive years, demonstrates that there was a consistent and systematic approach to depicting the king’s likeness as his reign progressed, whether devised as an individual portrait or as part of a set. Compositionally the group shows similarities in the positioning of the king, bust-length, facing slightly right, which agrees with standard royal “portrait set” type. We also see parallels in his appearance: in all three there is the emergence of a pattern of the king’s facial hair, with a small moustache that runs into a close-shaven beard, and in terms of physiognomy his face is slim and his eyes are heavily hooded, a distinctive characteristic of Vanson’s portraits. There are further consistencies with the king’s dress: he wears a doublet trimmed with gold or silver braid, and the distinctive tall-crowned hat is decorated with a feathered hat jewel. Additionally, all three have similar inscriptions on the top right of the panels recording James’s identity and age and the year in which the portrait was painted, a consistency found across the portraits ascribed to Vanson.

As well as relating to each other, the portraits show stylistic and technical consistencies with other works from Vanson’s oeuvre, which pre-date and post-date the group. Vanson typically used viscous paint, which he applied in a vigorous and free manner. To create texture and definition, principally in the face and hair elements, he often scored the paint layers with a sharp implement, probably the opposite end of his brush. These stylistic features can be observed in the Falkland portrait of 1586, the Ham House portrait of John Maitland of 1589, and the iconic 1595 portrait of James, aged twenty-nine, in the collection of National Galleries Scotland (NGS), a portrait considered to be the standard royal image of the king during his Scottish period (fig. 8). In both the Ham House and NGS portraits the artist has used the scoring technique to create wrinkles in the foreheads of his sitters. Another stylistic similarity found across these portraits is the idiosyncratic approach to depicting jewellery and precious metals. Having analysed the NGS portrait, the technical art historian Caroline Rae observes: “examination in stereomicroscopy suggested that at least three hands were at work in creating the portrait of James. The looser, more confident style used to create the sitter’s face and cloak contrasts with the more systematic techniques used to paint the decorative details”.40 This evidence points to workshop involvement in the production of this painting, which is unsurprising given Vanson’s status. Comparing the approaches in the depiction of the decorative details of the clothing with the jewellery, Rae notes that “a different hand appears to have been at work in the creation of the jewelled hat-band. This artist combines precise, deft strokes with a freer application of paint”.41 This method of depicting the jewels appears to be consistent between the Falkland, the NGS, and the German portraits, which strengthens the proposed attribution to Vanson.42

40

With respect to the facial pattern employed by the artist, the ex-Castle Fraser and German portraits act as predecessors to the NGS portrait of the king and the related miniature version also attributed to Vanson in the NGS collection.43 While the NGS painting is significantly larger than the three portraits, this is to be expected with a departure from the “portrait set” representations of the king to a more striking official royal image.44

43The date of the three portraits, painted in the years following James and Anna’s marriage of 1589, is also worth discussion. The first half of the 1590s saw intense speculation around the royal couple’s relationship as the court and public eagerly awaited news of a royal pregnancy. Both German portraits show James in green, a colour often worn for hunting in the spring and summer months but conspicuously also a colour associated with fertility, typically worn by female sitters.45 Did James make this sartorial choice to convey his and Anna’s long hoped-for heir? Indeed, by 1593 the king and queen and the nation’s expectations were realised when it was announced that Anna was pregnant. In a signet letter dated 1593 the anonymous author reflects on the reception of the news, that it was “to the conforte [comfort] alsweill [as well as] of us as of all our gude [good] and faithfull subiectis [subjects]”.46

45These years also saw an intensified campaign by the king and his advisers to secure James’s place as Elizabeth’s successor. The survival of two of these portraits, remarkably in the same country that they had arrived in, is evidence that the king and queen of Scots were engaged in a strategic programme of patronage and circulation of James’s visual image to princely rulers abroad. Their agenda was to promote James on the European stage, specifically as a Protestant ruler who sought recognition and relations with other heads of Protestant states. By doing so he was demonstrating to Elizabeth both his suitability and aspiration to be her successor. It is unsurprising that these portrait commissions, made during Vanson’s tenure as James’s court painter, were undertaken by him and his workshop. James was a shrewd king and would have been conscious that engaging a Protestant Netherlandish artist to create these portraits, destined for European Protestant states, would further emphasise his commitment to the Protestant cause.

Objects Struck in Gold

The Hessen–Kassel portrait of 1591 relates directly to two precious metal objects—the 1592 “Hat Piece” coin (fig. 9) and a gold medal from around 1590 traditionally said to commemorate James and Anna’s wedding (fig. 10). On the obverse of the Hat Piece is a head and shoulders portrait of James in profile wearing his distinctive tall hat embellished with a feathered hat jewel. Discussing the coin’s design, the art historian Duncan Thomson, former director of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, writes that “in the king’s iconography it [the coin] fills the gap between the beardless young man of 1586 … and maturely bearded man of the later portrait”.47 The portraits referenced in this quote are the Falkland and NGS depictions of James, both attributed to Vanson, discussed previously. The attribution of the ex-Castle Fraser and German portraits to Vanson addresses this hiatus and they a provide evidence of a consistent approach to royal portrait commissioning over these years.

47

The pattern of the 1591 portrait appears to be replicated in another precious object, the so-called Marriage Medal. This medal was cast in gold, but silver and base metal versions were also made that survive today in public collections.48 The similarities to the 1591 portrait are indisputable. On the obverse of the medal, as in the painted portrait, James is depicted wearing a doublet with chevron stripes and a small, flat linen collar, a tall hat with petal-shaped decorations, and a hatband with an identical feathered jewel at the centre. The representation of Anna meanwhile is close but not identical to the miniature painting of the queen, also attributed to Vanson, where Anna’s hair is piled up high on either side of her head in a halo style and she wears a large figure-of-eight ruff (fig. 11).

48

The legend on the obverse reads “IACOBVS 6 . ET . ANNA . D . G . SCOTORVM . REX . ET . REGINA”, while on the reverse is Scottish heraldic imagery: a shield with lion rampant at the centre, above a helmet, and two standards to the sides, the Scottish saltire on the right and the Danish wyvern (a distinctive Scandinavian dragon) on the left. The supporters are both unicorns, with large thistles behind them. Around the shield are the collar and badge of St. Andrew, and the royal motto, “IN DEFENCE”. With the exception of the small standard bearing the wyvern, the iconography on the reverse is predominantly Scottish. This seems unusual, given that the medal is traditionally said to commemorate James and Anna’s union. I propose an alternative interpretation that the medal was made to commemorate the baptism of Prince Henry Frederick, which took place at Stirling Castle on 30 August 1594.

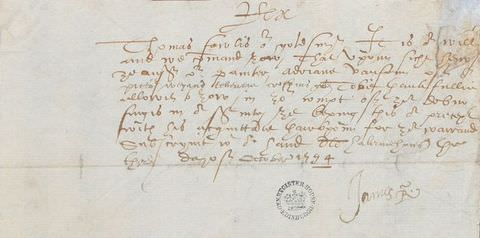

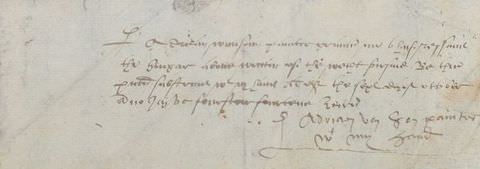

Archival sources record that medals were made to be presented to attendees. A collection of papers of Foulis’s accounts held by National Records of Scotland, transcribed by the historians Michael Pearce and Miles Kerr-Peterson, provides evidence of a medal being associated with and presented to Adrian Vanson. An entry dated 3 October 1594 records that “Adriane the painter” was presented with a gold medal weighing “twenty crowns”, with portraits of the king and queen:

Given the content of these documents and the portrait iconography on the surviving medals, which relate directly to portraits painted by Vanson in the early 1590s, I suggest that Vanson designed the portraitss of James and Anna for the medal, which were subsequently made into dies by Foulis and struck at the Royal Mint in Edinburgh. These medals were then presented to ambassadors and dignitaries at the baptism to commemorate this historic occasion.

These extraordinary documents not only reveal Vanson’s artistic contribution to marking the celebrations but also, significantly, provide evidence of James acknowledging and directly rewarding the artists in his service. The presentation of the medal emphasises Vanson’s status and relationship with the king, which in turn demonstrates James’s active participation in commissioning art and commemorative objects. As with the twenty-pound piece coin and associated woodcut discussed earlier, these archival sources evidence how these artists and craftspeople were interconnected, with artists supplying portrait patterns for designs for newly commissioned coins and commemorative medals. While the media the artists worked with may have differed, they had a shared agenda: to mark and commemorate key events in James and Anna’s lives.

Family Jewels, Political Tools

The significance of James and Anna’s union, and her subsequent arrival in Scotland, cannot be underestimated, particularly in the public consciousness. She was the first queen, albeit a queen consort, the country had seen since Mary’s forced abdication in 1567, and her ceremonial entry into the city of Edinburgh in 1590 was a pageant full of spectacle, rooted in Renaissance tradition and imbued with highly political and dynastic messaging. The symbol of a renewed optimism in the country, this fourteen-year-old foreign princess represented the continuity of the Stuart line and stability for the realm, and emphasised Scotland’s diplomatic and natal ties with northern Europe. James promoted the illustrious heritage of his new queen, the daughter of a king who was brother to a future king, as well as the mother to a future king. Significantly “a faire jewell, of a great price, called the A, was givin to the queene” at her entry by the burgh council.51

51Jemma Field’s research on Anna of Denmark and the Scottish jeweller George Heriot has revealed that in the queen’s first account with the jeweller, dated May 1593, there are two entries for “hir majesties Sipher”, one of which was set with an extraordinary twenty-eight diamonds and sixteen rubies.52 As Field acknowledges, this commission for two cipher jewels from Heriot was the beginning of a series of acquisitions of emblematic jewels that Anna collected, wore, and gifted throughout her life. Given the timing of this entry, approximately nine months before the birth of the couple’s first child, Prince Henry Frederick, could Anna’s commission for the cipher jewels relate to her pregnancy? It is tantalising to think this entry may record payment for a jewel that appears conspicuously in two portraits of the king. The half-length portrait of James VI by Vanson and the associated miniature portrait on panel both show James wearing a large diamond initial “A” jewel at the centre of an embellished hatband (see figs. 8 and 14).

52

In the larger of the two portraits the band of the hat jewel is constructed from further jewelled initials including a letter “H”, referencing Prince Henry Frederick; an “E”, which could be interpreted as symbolising Elizabeth I (Henry’s godmother); and an “I” perhaps alluding to James himself. Even if this “A” cipher is not the exact jewel that is represented, the portraits may give some insight into how James wore this type of jewellery and employed it as a vehicle for disseminating messages around dynasty, legacy, and allegiance.

Jewellery was a distinctive part of Anna’s identity, and she had a sophisticated understanding of how it could be used for political advantage. In January 1599, when discussions around the succession were at their height, Anna asked Jousie to procure her a sapphire engraved with Elizabeth’s portrait from London. Accounts record that he paid a stonecutter called Cornelius Deady for “ane blew sapher quhairupone he had wrochtt and cuttit the quenes majestie portrait”.53 Anna’s strategic acquisition of this jewel was politically charged: as the Scottish queen consort, she was demonstrating her affection for the English queen and signposting her allegiance, and by association the jewel communicated James’s affection and allegiance to Elizabeth and ultimately his ambition to become her successor.

53Print and the Bright Star of the North

As demonstrated, portraiture played a key role in disseminating the king’s image, yet it was not only painted portraits but also engraved portraits that were produced to circulate the royal image. In contrast to his comment on the painted portraiture of James, Roy Strong held a more favourable view of the pre-1603 print culture related to James, explaining that “the most important engravings of James are the early ones which illuminate the less documented part of his iconography”.54 This is true. However, engravings not only acted as important iconographical sources but also played a formative role in constructing and promoting James’s image and identity as the successor to the English throne. He placed his family at the centre of this visual imagery, exploiting his illustrious heritage as descended from the house of Stuart and his immediate family, both Anna, a European princess from the house of Oldenberg, and his children. In her work on Stuart familial propaganda Catriona Murray stresses the significance of the use of this type of imagery, explaining that “dynastic and domestic representations were strategically developed to endorse political agendas”.55 At the heart of James’s political agenda in the 1590s was the English succession and regnal union.

54

In an engraving by an unknown artist in the British Museum James is portrayed full-length, standing in front of an architectural arch inscribed with his title in Latin, “IACOBUS VI. REX SCOTORUM”, wearing a doublet and hose, short ermine-trimmed cloak, figure-of-eight ruff, and his distinctive high-crowned hat (fig. 15). To the right of the king, above the table on which the imperial Scottish crown is placed, we see the Scoto-Danish arms, supported by the Scottish unicorn and the Danish wyvern. James and Anna’s union is emphasised here, as is James’s sovereignty. A second state was published to include the young Prince Henry Frederick, dressed in skirts.56 The pendant to this engraving features a portrait of Anna, standing full-length, also in front of an arch, accompanied by an infant Princess Elizabeth, who was born in August 1596 (fig. 16).57 A second state of this print shows Anna, with Princess Elizabeth accompanied by her brother (fig. 17).

56

This group of prints attests to the significance placed on the royal children.58 In stark contrast to Queen Elizabeth, who embodied the figure of the Virgin Queen and was acclaimed for her chastity, Murray explains that “James’s portrayal instead prioritised the fulfilment of his kingly duties to take a wife and to produce children. Texts and images referenced both his ancestry and his offspring, articulating reassuring messages about the stability and continuity of the Stuart dynasty, while presenting the king’s authority in patriarchal terms”.59 Messaging around legacy and security were key to James’s succession campaign. Elizabeth’s reluctance to name an heir created anxieties for her court, government, and subjects, whereas James, albeit a foreign king, would come to England with a wife, an heir, a spare, and an eligible daughter, alleviating any concerns around the future succession.

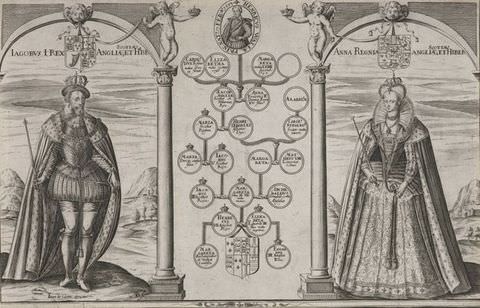

58At James’s accession a series of prints and broadsides, including those by Nicolaes de Bruyn, were issued outlining his ancestry and qualifying his hereditary claim to the English throne (fig. 18). Circulated to wide audiences, the imagery of James and Anna often featured illustrated genealogical trees that could be understood by non-readers. As well as illustrating James’s heritage, they recorded his offspring, highlighting Prince Henry Frederick as James’s true heir and the future king.

Royal arms, heraldry, and genealogical illustrations were not limited to printed material. Vibrantly coloured and gilded representations were found in the interiors and exteriors of royal and civic buildings including palaces, churches, tollbooths, and even ships. They were painted on banners, furniture, and ceilings; carved into stonework; moulded as decorative plasterwork; and incorporated into stained glass windows.60 James’s royal arms and heraldic devices would have been visible to both elite and non-elite individuals throughout the city of Edinburgh and those living in the royal burghs.

60Representations of ancestry and lineage were intrinsically wrapped up in James’s identity and were foregrounded in pageantry staged for significant events, including his first ceremonial entry into Edinburgh in 1579, where he processed under arches hung with portraits of the former Stuart kings who shared his name. Ten years later, around the time of his marriage in 1589, £43 Scots was paid to a “Highlandman” for making a “table of all the genologie of all the kingis of Scotland”.61 Lineage was again centre stage at James’s ceremonial entry into London in 1604, where the iconography on the temporary triumphal arches emphasised the king’s descent from Henry VII of England.

61Certainly, in England the early visual language of his reign focused on asserting James’s hereditary rights, with representations of his family past and present, and on James as a “Father King” and uniter of the kingdoms of Scotland, England, and Ireland. As some art historians have argued, James carried on Elizabeth’s visual legacy, retaining the services of painters including Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Robert Peake, and Nicholas Hilliard, and this may be viewed as a strategic choice to reassure his new court, government, and subjects and to provide a sense of continuity. However, the appointment in 1603 of the Flemish artist John de Critz as serjeant-painter marked a distinct departure in terms of James’s, and indeed Anna’s, royal iconography. In these full-length portraits by De Critz, and in their numerous derivatives, James centres three highly symbolic hat jewels: “The Feather”, a jewel constructed from twenty-six large diamonds, thought to have been sourced from Elizabeth I’s jewellery collection, set in a point to mimic a feather; the “Three Brothers”, comprising three balas rubies, configured around a central diamond and four large pearls; and most significantly the “Mirror of Great Britain” (fig. 19).62 The Mirror was a rhombus-shaped jewel constructed from three diamonds, two pearls, a large ruby, and as a pendant drop the magnificent fifty-five-carat Sancy diamond. This richly symbolic jewel was commissioned by James to mark both his accession and the Union of the Crowns, and he ensured that the Mirror was showcased in his official royal portraits. This article has therefore come full circle, from the discovery of a jewel in Scotland in 1570, rich in imagery and text alluding to a hoped-for Scottish succession to the Mirror, a reflective, shining embodiment of James’s realised ambition to become the first “king of Great Britain”.

62

Conclusion

The surviving examples of artwork, objects, and archival records from the mid-1560s to the early 1600s, considered together, provide evidence of James’s consistent engagement with and contribution to a rich programme of visual and material patronage during these decades in Scotland. This cultural output, which centred on thematic representations of family, power, and unity was considered, systematic, and strategic, and its foundations were rooted in James’s early cultural exchanges. It reveals that James was operating politically and culturally at not only a national but also a European level to ensure that his image was embedded in the picture galleries and minds of his continental counterparts. This counters traditional narratives surrounding James’s lack of enthusiasm for or participation in visual and material displays of majesty.

Moreover, this research augments what we currently recognise as Vanson’s oeuvre, ascribing three previously unpublished and unattributed portraits to the artist. It also highlights the significant position that Vanson, his kin, and associated cultural players in Edinburgh such as Thomas Foulis held in relation to the Crown. By embracing an inclusive approach to early modern Scottish art and material culture, the article has revealed the interconnected nature of artistic production in late sixteenth-century Edinburgh and highlights how much there is still to uncover.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Michael Pearce who has generously shared much of his research and key archival references relating to Bronckorst and Vanson and enthusiastically discussed my research with me. I would also like to thank my co-editors for this special issue, Catriona Murray and Jemma Field, for their support with this article and for their shared enthusiasm for King James; and Baillie Card and Tom Powell for their editorial support and guidance for this special issue.

About the author

-

Kate Anderson is Senior Curator, Portraiture (Pre-1700) at the National Galleries of Scotland where she has responsibility for the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century collections. Her research interests focus on the visual and material culture of the early modern period, specialising in portraiture and self-fashioning at the Stuart courts from about 1560 to 1715. In 2025 she curated the exhibition The World of King James VI & I (National Galleries of Scotland, Portrait) and edited the accompanying publication Art & Court of James VI & I (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025). Her current research focuses on the British baroque artist John Michael Wright.

Footnotes

-

1

Roy Strong, Tudor and Jacobean Portraits (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1969), 178. ↩︎

-

2

Sir Anthony Weldon, The Court and Character of King James, Written and Taken by Sir. A: W: Being an Eye, and Eare Witnesse (London: printed by R.I. and sold by John Wright, 1650). ↩︎

-

3

Michael Bath, Renaissance Decorative Painting in Scotland (Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 2003). ↩︎

-

4

Robert Tittler, Early Modern British Painters, c.1500–1640, unpublished dataset (2015, rev. 2024). ↩︎

-

5

For scholarship on Vanson, see Duncan Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 1570–1650 (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1975), exhibition catalogue; David Taylor, “Gesture Recognition: Adam de Colone and the Transmission of Portrait Types from the Low Countries and England to Scotland”, in Painting in Britain, 1500–1630: Production, Influences, and Patronage, ed. Tarnya Cooper et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 311–23; Caroline Rae, with Kate Anderson and David Taylor, “New Thoughts on Adrian Vanson: Findings from a Technical Examination of Selected Works, Including the Discussion of an Interesting Panel Join”, Picture Restorer 61 (Autumn 2022): 35–46; Caroline Rae, “New Perspectives on the Sheffield Portraits of Mary, Queen of Scots including the Discovery of a New, Related, Contemporary Portrait”, in The Afterlife of Mary, Queen of Scots, ed. Steven Reid (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 53–83. ↩︎

-

6

Miles Kerr-Peterson and Michael Pearce, “King James VI’s English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts, 1588–1596”, Scottish History Society Miscellany 16 (2020): 1–92. ↩︎

-

7

Helen Wyld, “The Mystery of the Fettercairn Jewel”, in Decoding the Jewels: Renaissance Jewellery in Scotland, ed. Anna Groundwater (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2024), 61–86. ↩︎

-

8

George Lasry, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters from 1578–1584”, Cryptologia 47, no. 2 (2023): 56, DOI:10.1080/01611194.2022.2160677. I am grateful to Michael Pearce for sharing this reference with me. This could be interpreted as a new portrait type by Arnold Bronckorst, who had received payment for paintings in September 1581, £46 paid to him for “certane picturis”, or it could suggest a portrait painted by a new artist. Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1580, National Records of Scotland (NRS), Edinburgh, E21/62, fol. 162, cited in Michael R. Apted and Susan Hannabuss, Painters in Scotland, 1301–1700: A Biographical Dictionary (Edinburgh: Edina Press, 1978), 31. ↩︎

-

9

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Vouchers of account of William, Lord Ruthven, Treasurer, February, April, August, September, and December 1581, NRS, E23/6/17, which appears to relate to NRS, E21/62, fol. 162 (1581–82), above, as the total for the two portraits come to £46. I am grateful to Michael Pearce for sharing details and a transcription of this precept, which is damaged and has been restored. ↩︎

-

10

Lettres, instructions et mémoires de Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse: publiés sur les originaux et les manuscrits, vol. 6, ed. Alexandre Labanoff (London: Charles Dolman, 1844), 271. ↩︎

-

11

D’Esneval à Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse, à la reine Catherine de Médicis et au roi Henri III. Fackland, 3 July 1586, Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), Paris, Français 4736, fols. 319–320. Given this date, the painter could be identified as Adrian Vanson. A portrait of James aged twenty, dated 1586 and attributed to Vanson, is discussed in the next section. ↩︎

-

12

Registre de monsieur Pinart, secretaire d’Estat soubs le regne d’Henry 3me, de diverses instructions et despesches aux ambassadeurs, BnF, Français 3305, fol. 11r, cited in Lettres de Catherine de Médicis, vol. 9, 1582–1585, ed. Gustave Baguenault de Puchesse (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1835), 18. ↩︎

-

13

D’Esneval à Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse, à la reine Catherine de Médicis et au roi Henri III, BnF, Français 4736, fols. 319–320. There is evidence to suggest that this painting is the portrait attributed to Adrian Vanson at Edinburgh Castle (Historic Environment Scotland, EDIN038), as the painting has an early Danish provenance, although reservations remain surrounding the attribution, and further research and technical analysis is required. ↩︎

-

14

For more on the Association see Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes, “Joint Iconography for Joint Sovereigns: Mary Queen of Scots, James VI of Scotland, and the Campaign for Association, c. 1578–1584”, in Women and Cultures of Portraiture in the British Literary Renaissance, ed. Yasmin Arshad and Chris Laoutaris (London: Bloomsbury, in press). I am grateful to the authors for sharing an advance draft of their article with me. ↩︎

-

15

Vanson’s parents have recently been identified as Willem Claesswen van Son and Kathelijn Adriaen Matheus de Blauwverversdochter. Nathan W. Murphey and Leslie Mahler, “The King, Vanson, and de Colonia Ancestors of William Fitzhugh of Virginia”, American Genealogist 88 (2016): 152–57. ↩︎

-

16

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1580, NRS, E21/61, fol. 19. ↩︎

-

17

Stephen Atkinson, The Discoverie and Historie of the Gold Mynes in Scotland, Written in the Year 1619 (Edinburgh: James Ballantyne, 1825), 33–35. ↩︎

-

18

Register of the Privy Seal, NRS, PS 1/47, fol. 40. For pension payments see Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1582–83, NRS, E21/63, fols. 46, 95, cited in Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 22. ↩︎

-

19

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1581–82, NRS, E21/62, fol. 169, cited in Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 31. ↩︎

-

20

Taylor, “Gesture Recognition”, n8. ↩︎

-

21

Vanson had kin in London, notably the painter Peter Matheeusen, who was his cousin and who in 1588 left him a bequest of portraits and a copy of Hilliard’s Treatise Concerning the Art of Limning. Matheeusen also left bequests to Isaac Oliver and Rowland Lockey. Edward Town, “A Biographical Dictionary of London Painters, 1547–1625”, Volume of the Walpole Society 76 (2014): 140–41. ↩︎

-

22

As part of his role as burgess, Vanson was expected to take on apprentices, but we currently have no evidence relating to his workshop. Vanson retained the role of the king’s painter until James’s accession to the English throne in 1603 and subsequently followed the king to London, where he is recorded as working on the Dutch triumphal arch, one of seven temporary structures created for James’s ceremonial entry into the city in 1604. Town, “A Biographical Dictionary”, 183. ↩︎

-

23

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1581–82, NRS, E21/62, fol. 135v, cited in Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 25–26. ↩︎

-

24

Peter Hume Brown, John Knox: A Biography, vol. 2 (London: A. & C. Black, 1895), 320–24, cited in Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 26, catalogue no. 10. ↩︎

-

25

The iconography and sources for the woodcut, the significance of Icones, and the motives surrounding Beza’s dedication to James are discussed in Susan Doran, David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt, and Paulina Kewes, “Visualising James VI and I in Continental Europe”, British Art Studies 29 (December 2025), DOI:https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/sdoranetal. ↩︎

-

26

Will of Michael Gilbert, NRS, CC8/8/23, fol. 564, cited in Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 25. ↩︎

-

27

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1581–82, NRS, E21/62, fol. 169, cited in Apted and Hannabuss, Painters in Scotland, 99. ↩︎

-

28

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1581–82, NRS, E21/62, fol. 180, cited in Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 31, catalogue no. 21. ↩︎

-

29

Foulis’s business partner was Robert Jousie, the Edinburgh-based cloth merchant who was consistently recorded in the Treasurer’s accounts as procuring luxury fabrics, clothes, and accessories for the royal wardrobe. For more on Robert Jousie see Jemma Field, “Dressing a Queen: The Wardrobe of Anna of Denmark at the Scottish Court of King James VI, 1590–1603”, Court Historian 24, no. 2 (2019): 154–55; and Kerr-Peterson and Pearce, “King James VI’s English Subsidy”. ↩︎

-

30

For more on the economic role of goldsmiths, see Bruce P. Lenman, “Jacobean Goldsmith Jewellers as Credit-Creators: The Cases of James Mossman, James Cockie and George Heriot”, Scottish Historical Review 74 (1995): 159–77. ↩︎

-

31

A double-sided portrait of Patrick Lyon, ninth Lord Glamis, dated 1583, in the Glamis Castle collection has been associated with Vanson, and if this attribution is correct the portrait would be the earliest extant portrait by Vanson. Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 26, catalogue no. 12. ↩︎

-

32

For a detailed analysis of these works see Kate Anderson, “Painting the Precious: Renaissance Jewellery in Scottish Portraits”, in Decoding the Jewels: Renaissance Jewellery in Scotland, ed. Anna Groundwater (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2024), 129–54. ↩︎

-

33

Rae, “New Thoughts on Adrian Vanson”. ↩︎

-

34

Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 26, catalogue no. 12. Thomson was the first to suggest the Vanson attribution for this portrait. ↩︎

-

35

See the black-and-white image record in James VI and I sitter files in the archive of the Portrait Gallery, National Galleries of Scotland, SPh II 79.1–279. Castle Fraser and its collections have been under the care of the National Trust for Scotland since 1976. Frederick Hepburn, “Portraits of James I and James II, Kings of Scots: Some Comparisons and a Conjecture”, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 148 (2018): 226n20. ↩︎

-

36

Email correspondence with Justus Lange, curator, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Hessen Kassel Heritage, between 19 September and 8 October 2024. The painting is first recorded in an inventory of 1816 following the end of the Napoleonic occupation of Kassel, which lists it as being in the gallery collection. I am grateful to Dr Lange for this information. ↩︎

-

37

The portrait is mentioned but not illustrated in Hepburn, “Portraits of James I and James II”, 218. ↩︎

-

38

Inventory no. 3042. I would like to thank Mirjam Neumeister, chief curator of Flemish baroque painting at the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, for supplying the provenance information for the painting. The inventory of the collection was ordered by Wilhelm’s son Maximilian I in February 1598, immediately following his father’s abdication. The inventory is published in Dorothea Diemer et al., eds., Die Münchner Kunstkammer, 3 vols. (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2008). ↩︎

-

39

Letter from Christian IV of Denmark–Norway to James VI of Scotland, 8 October 1597, NRS, SP13/128/1. ↩︎

-

40

Rae, “New Thoughts on Adrian Vanson”, 41. ↩︎

-

41

Rae, “New Thoughts on Adrian Vanson”, 41. ↩︎

-

42

As the ex-Castle Fraser portrait is untraced and only a low-quality black-and-white image exists, it is impossible to assess the specific painting technique of the jewellery elements. ↩︎

-

43

James VI and I, attributed to Adrian Vanson, oil on panel, 1595, National Galleries of Scotland (PG 1109), pendant to Anna of Denmark (PG1110) (see (fig. 14)). ↩︎

-

44

The panel has been cut down at the bottom and left edges. This explains the odd composition, with the king positioned far to the left. The painting was accompanied by a pendant portrait of Anna of Denmark, now lost. ↩︎

-

45

As noted earlier, the ex-Castle Fraser image is in black and white, and so it is not possible to comment on the colour of James’s doublet. With thanks to Jemma Field for this information on the symbolism associated with the colour green. ↩︎

-

46

“Signet letters narrating that as Anne of Denmark was now pregnant (Henry, Duke of Rothesay, born 19 February 1593/4)”, 18 January 1593, NRS, RH15/19/10. ↩︎

-

47

Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 31, catalogue no. 22. ↩︎

-

48

In addition to the gold example in the Royal Museums Greenwich, there are silver versions in the collections of the National Museum of Scotland (H.R 15) and the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow (MI.I.157.136). ↩︎

-

49

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Vouchers of the accounts of Thomas Foulis May 1594–May 1596, NRS, E30/14, fol. 5r, reprinted in Kerr-Peterson and Pearce, “James VI’s English Subsidy”, 83. It reads, in modernised English: “Item to Adrian the painter one medal with the king and queen’s portrait weighed in gold twenty crowns. By virtue of his majesties precept at Holyroodhouse the third day of October in the year 1594 … 60 pounds”. ↩︎

-

50

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Vouchers of the accounts of Thomas Foulis May 1594–May 1596, NRS, E30/15/3, reprinted in Kerr-Peterson and Pearce, “James VI’s English Subsidy”, appendix 1, 87–88. The description of it as a “hingar” may suggest that it was mounted and attached to a chain or ribbon. It reads, in modernised English: “I Adrian Vanson painter grant me to have received the hingar [the medal] above written of the weight abovementioned. By these present signed by my hand at Edinburgh on the sixth day of October 1594. [Signed] Adrian Van Son painter with my hand”. ↩︎

-

51

David Calderwood, The History of the Kirk of Scotland, vol. 5 (Edinburgh: Wodrow Society, 1842), 97. ↩︎

-

52

Itemized account of jewels supplied to the Queen by George Heriot Younger in the months of May and August 1593, NRS, GD421/1/3/5, cited in Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 141. ↩︎

-

53

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Volume of accounts of the king’s and queen’s apparel furnished by Robert Jousie, merchant, at the direction of Sir George Home, master of the wardrobe, 1590–1600, NRS, E35/13 (8), p. 34, cited in Michael Pearce, “Anna of Denmark: Fashioning a Danish Court in Scotland”, Court Historian 24, no. 2 (2019): 141. A rare Jacobean locket with a large sapphire cameo portrait of Elizabeth I was sold for £11,000 at Christie’s on 15 October 1992 from the collection of the earl of Northesk https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-2976405. ↩︎

-

54

Roy Strong, Tudor and Jacobean Portraits (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1969), 180. ↩︎

-

55

Catriona Murray, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), passim. ↩︎

-

56

British Museum, 1864,0813.102. ↩︎

-

57

The British Museum online collection record dates this engraving to circa 1602, although I would suggest a slightly earlier date, given Princess Elizabeth’s appearance. ↩︎

-

58

The figures of James, Anna, and Henry would be reused for the engraved title page of The Lawes and Acts of Parliament (1597), printed by Robert Waldegrave, “printer to the Kings Majestie”, in Scotland. ↩︎

-

59

Catriona Murray, “James VI and I, The Pageantry of Fatherhood”, in Kate Anderson, Art & Court of James VI & I (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025), exhibition catalogue, 29. ↩︎

-

60

In addition to painting portraits for the Crown in 1589, Vanson was paid for painting the Danish arms on banners in preparation for Anna of Denmark’s coronation. James Thomson Gibson-Craig, Papers Relative to the Marriage of King James the Sixth of Scotland (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1836), appendices 11 and 16. ↩︎

-

61

Kerr-Peterson and Pearce, “James VI’s English Subsidy”, 12, 22. ↩︎

-

62

The Three Brothers is recorded in a watercolour in the collection of the Historisches Museum Basel (Inv.1916.475). It was a jewel with an extraordinary heritage, first recorded in the possession of Duke John the Fearless. James sent it to George Heriot to be remounted in preparation for Prince Charles’s trip to Madrid to woo the Spanish infanta Maria Anna in 1623. The Sancy diamond was the largest known pale yellow diamond at the time and had an extraordinary lineage, having belonged to French kings before it was sold to James in 1604. It is now in the collection of the Louvre, Paris. For more on these jewels see Roy Strong, “Three Royal Jewels: The Three Brothers, the Mirror of Great Britain and the Feather”, Burlington Magazine 108 (1966): 350–53. ↩︎

Bibliography

Manuscript Sources

Accounts of Thomas Foulis, 1594–96. E30/14. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

D’Esneval à Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse, à la reine Catherine de Médicis et au roi Henri III. Fackland, le 3 juillet 1586, Français 4736, fols. 319–320. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1580. E21/61, fol. 19; E21/62, fol. 162v. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1581–82. E21/62, fols. 135v, 162, 169. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, 1582–83. E21/63, fols. 46, 95. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Volume of accounts of the king’s and queen’s apparel furnished by Robert Jousie, merchant, at the direction of Sir George Home, master of the wardrobe, 1590–1600. E35/13 (8), p. 34. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Vouchers of account of William, Lord Ruthven, Treasurer, February, April, August, September, and December 1581. E23/6/17. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Exchequer Records: Accounts of the Treasurer, Vouchers of the accounts of Thomas Foulis, May 1594–May 1596. E30/14, fol. 5r; E30/15/3. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Itemized account of jewels supplied to the Queen by George Heriot Younger in the months of May and August 1593. GD421/1/3/5. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

James VI and I sitter files, SPh II 79.1–279, National Galleries of Scotland, Portrait Library and Archive, Edinburgh.

Letter from Christian IV of Denmark–Norway to James VI of Scotland, 8 October 1597. SP13/128/1. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Register of the Privy Seal. PS1/47, fol. 40. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Registre de monsieur Pinart, secretaire d’Estat soubs le regne d’Henry 3me, de diverses instructions et despesches aux ambassadeurs, Français 3305, fol. 11r. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Signet letters narrating that as Anne of Denmark was now pregnant (Henry, Duke of Rothesay, born 19 February 1593/4), 18 January 1593. RH15/19/10. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Will of Michael Gilbert. CC8/8/23, fol. 564. National Records of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Printed Sources

Anderson, Kate. “Painting the Precious: Renaissance Jewellery in Scottish Portraits”. In Decoding the Jewels: Renaissance Jewellery in Scotland, edited by Anna Groundwater, 129–54. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2024.

Anderson, Kate, with Catriona Murray, Jemma Field, Anna Groundwater, Karen Hearn, and Liz Louis. Art & Court of James VI & I. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025. Exhibition catalogue: National Galleries of Scotland.

Apted, Michael R., and Susan Hannabuss. Painters in Scotland, 1301–1700: A Biographical Dictionary. Edinburgh: Edina Press, 1978.

Atkinson, Stephen. The Discoverie and Historie of the Gold Mynes in Scotland, Written in the Year 1619. Edinburgh: James Ballantyne, 1825.

Bath, Michael. Renaissance Decorative Painting in Scotland. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 2003.

Brown, Peter Hume. John Knox: A Biography. Vol. 2. London: A. & C. Black, 1895.

Calderwood, David. The History of the Kirk of Scotland. Vol. 5. Edinburgh: Wodrow Society, 1842.

Diemer, Dorothea, Peter Diemer, Lorenz Seelig, Peter Volk, and Brigitte Volk-Knüttel, eds. Die Münchner Kunstkammer. 3 vols. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2008.

Doran, Susan, and Paulina Kewes. “Joint Iconography for Joint Sovereigns: Mary Queen of Scots, James VI of Scotland, and the Campaign for Association, c. 1578–1584”. In Women and Cultures of Portraiture in the British Literary Renaissance, edited by Yasmin Arshad and Chris Laoutaris. London: Bloomsbury, in press.

Doran, Susan, David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt, and Paulina Kewes. “Visualising James VI and I in Continental Europe”. British Art Studies 29 (December 2025). DOI:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/sdoranetal.

Field, Jemma. Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Field, Jemma. “Dressing a Queen: The Wardrobe of Anna of Denmark at the Scottish Court of King James VI, 1590–1603”. Court Historian 24, no. 2 (2019): 152–67.

Gibson-Craig, James Thomson. Papers Relative to the Marriage of King James the Sixth of Scotland. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, 1836.

Hepburn, Frederick. “Portraits of James I and James II, Kings of Scots: Some Comparisons and a Conjecture”. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 148 (2018): 209–29.

Juhala, Amy. “The Household and Court of King James VI of Scotland, 1567–1603”. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2000.

Kerr-Peterson, Miles, and Michael Pearce. “King James VI’s English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts, 1588–1596”. Scottish History Society Miscellany 16 (2020): 1–92.

Lasry, George, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo. “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters from 1578–1584”. Cryptologia 47, no. 2 (2023): 101–202. DOI:10.1080/01611194.2022.2160677.

Lenman, Bruce P. “Jacobean Goldsmith Jewellers as Credit-Creators: The Cases of James Mossman, James Cockie and George Heriot”. Scottish Historical Review 74 (1995): 159–77.

Lettres de Catherine de Médicis. Vol. 9, 1582–1585. Edited by Gustave Baguenault de Puchesse. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1835.

Lettres, instructions et mémoires de Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse: publiés sur les originaux et les manuscrits. Vol. 6. Edited by Alexandre Labanoff. London: Charles Dolman, 1844.

Lenman, Bruce P. “Jacobean Goldsmith Jewellers as Credit-Creators: The Cases of James Mossman, James Cockie and George Heriot”. Scottish Historical Review 74, part 2, no. 198 (October 1995): 159–77.

Murphey, Nathan W., and Leslie Mahler. “The King, Vanson, and de Colonia Ancestors of William Fitzhugh of Virginia”. American Genealogist 88 (2016): 152–57.

Murray, Catriona. Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Murray, Catriona. “James VI and I, The Pageantry of Fatherhood”. In Kate Anderson, with Catriona Murray, Jemma Field, Anna Groundwater, Karen Hearn, and Liz Louis, Art & Court of James VI & I, 29–39. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025. Exhibition catalogue: National Galleries of Scotland.

Pearce, Michael. “Anna of Denmark: Fashioning a Danish Court in Scotland”. Court Historian 24, no. 2 (2019): 138–51.

Rae, Caroline. “New Perspectives on the Sheffield Portraits of Mary, Queen of Scots including the Discovery of a New, Related, Contemporary Portrait”. In The Afterlife of Mary, Queen of Scots, edited by Steven Reid, 53–83. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

Rae, Caroline, with Kate Anderson and David Taylor. “New Thoughts on Adrian Vanson: Findings from a Technical Examination of Selected Works, Including the Discussion of an Interesting Panel Join”. Picture Restorer 61 (Autumn 2022): 35–46.

Strong, Roy. “Three Royal Jewels: The Three Brothers, the Mirror of Great Britain and the Feather”. Burlington Magazine 108 (1966): 350–53.

Strong, Roy. Tudor and Jacobean Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery, 1969.

Taylor, David. “Gesture Recognition: Adam de Colone and the Transmission of Portrait Types from the Low Countries and England to Scotland”. In Painting in Britain, 1500–1630: Production, Influences, and Patronage, ed. Tarnya Cooper et al., 311–23. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Thomson, Duncan. Painting in Scotland, 1570–1650. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 1975. Exhibition catalogue: Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh.

Tittler, Robert. Early Modern British Painters, c.1500–1640. Unpublished dataset, 2015, rev. 2024.

Town, Edward. “A Biographical Dictionary of London Painters, 1547–1625”. Volume of the Walpole Society 76 (2014).

Weldon, Sir Anthony. The Court and Character of King James, Written and Taken by Sir. A: W: Being an Eye, and Eare Witnesse. London: printed by R.I. and sold by John Wright, 1650.

Wyld, Helen. “The Mystery of the Fettercairn Jewel”. In Decoding the Jewels: Renaissance Jewellery in Scotland, edited by Anna Groundwater, 61–86. Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2024.

Imprint

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 December 2025 |

| Category | Article |

| Review status | Peer Reviewed (Double Blind) |

| License | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) |

| Downloads | PDF format |

| Article DOI | https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/kanderson |

| Cite as | Anderson, Kate. “‘Certane Picturis of His Majesties Visage’: Tracing James VI’s Succession Campaign through Visual and Material Display and Dissemination.” In British Art Studies: Reframing King James VI and I (Edited by Kate Anderson, Jemma Field, and Catriona Murray.). London and New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art, 2025. https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-29/kanderson. |