Visualising James VI and I in Continental Europe

Visualising James VI and I in Continental Europe

By Susan Doran David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt Paulina Kewes

Abstract

The article charts the European circulation of James’s images from cradle to grave, elucidating their contexts and their ideological and commercial ramifications. Some, notably miniatures and full-length portraits made in Scotland and, after 1603, in England, served as diplomatic gifts. They attest to James’s keen cultivation of his—and his dynasty’s—visual brand. Others, mainly engravings by Dutch, German, and French artists originating on the continent, circulated individually or were inserted into printed compendia on royalty. Their proliferation and diversity, far exceeding those of James’s Scottish and English predecessors, testifies to the international appetite for the king’s likeness. Yet except for a brief interval in 1580–84, when a few continental engravings fuelled a cross-confessional contest over his future, James’s visualisations did not court controversy. Rather, they bear witness to his success as dynast, ruler, and author.

Introduction

Renaissance monarchs became increasingly alive to the international value of their visual image, especially as an ever-expanding print culture and increased capacity for international transmission and circulation of visual media made it possible to shape and publicise the royal image as never before. The Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I was among the first to exploit the political and ideological potential of his image, disseminating it through portraits, miniatures, and engravings.1 Later Habsburg monarchs followed Maximilian’s lead. Paintings and engravings of his grandson and heir, Charles V, that denoted his dynastic and imperial power circulated throughout Europe.2 Charles’s son, Philip II of Spain, promoted a vision of himself as a universal monarch and saviour of Western Christendom across the Iberian Peninsula, Europe, and the colonies of the Spanish–Portuguese Empire, through the media of portraits and their copies, miniatures, medals, and prints.3 Similarly, although on a much smaller scale, Christian IV of Denmark–Norway styled himself as a peacemaker after the 1629 Peace of Lübeck, and commissioned a series of portraits, engravings, and medals that glorified his rule and the Oldenburg dynasty.4 Some royal images were part of carefully planned diplomatic strategies to bolster international alliances; paintings, miniatures, and medals were gifted to foreign relatives to strengthen ties of kinship; and engravings were produced abroad, outside of the monarch’s own jurisdiction, to satisfy rising commercial demand. Images were also repurposed for polemical ends in the ever-changing religious and ideological conflicts of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Early modern princes thus faced the challenge of curating their visual image and controlling its transmission, even as developing markets and ideological differences made it increasingly difficult to do so.

1Like his fellow monarchs, King James took care to promote his image through medals, miniatures, full-length portraits, and engravings for a domestic audience.5 This much is well established. But what about abroad? In striking contrast to the foreign circulation of his writings, so amply documented by Astrid Stilma, continental depictions of James in engravings, portraits, prints, and drawings have been little studied.6 This article initiates an investigation into this significant and so far neglected subject. Among the questions we consider are: Who created the king’s images abroad, and what were the circumstances of their production and circulation? Did their transmission steadily increase or were they clustered around events of particular international importance? What messages were projected through their iconography and to what ends?

5Our enquiry develops in three stages. We begin with the first ever overview of James’s visualisations abroad; the second part explores the earliest images of James in continental printed books, revealing their centrality to the ideological warfare between Catholic and Protestant, legitimist and resister; and the third scrutinises the role of James’s portraits in the Scoto- and later Brito-Danish diplomacy. Overall, the article elucidates the development of James’s image in a European context and the changing meanings associated with it.

Images of James in Europe from Cradle to Grave

James gained widespread notoriety at barely one year of age as a result of his contested coronation as king of Scotland after his Catholic mother Mary’s deposition in July 1567. James’s exceptional constitutional position and Calvinist upbringing placed him at the centre of pan-European confessional conflicts.7 His search for a wife in the mid-1580s and his marriage in 1589 to Anna, the sister of Christian IV of Denmark–Norway, further stimulated interest in his physical appearance.8 After the wedding, his networks extended beyond Denmark and Norway to north Germany, where Anna’s three sisters came to live as wives to the elector of Saxony and the dukes of Brunswick–Lüneburg and Holstein–Gottorp. His international profile was further enhanced once he succeeded Elizabeth I as king of England and Ireland in 1603. Thenceforth, he styled himself king of Great Britain.

7Many of James’s portraits, which originated first in Scotland and later in England, are today housed in continental art galleries—in Vienna, Madrid, Munich, Florence, Amsterdam, and Stockholm.9 Documentary evidence suggests there were numerous others that have since been lost. Two small paintings of him by Adrian Vanson, no longer extant, were sent to Geneva before 1581, a destination determined by James’s confessional background.10 Following his majority and assumption of the reins of government, a three-quarter-length portrait painted between 1583 and 1585 was sent to Denmark when the Scottish court began negotiations for a marriage with Elisabeth, the elder daughter of King Frederick II (fig. 1). Two miniatures of the boy-king, now in the Rijksmuseum, may also have been produced in Scotland as gifts to highlight James’s suitability as a marital prospect.11

9

After his marriage to Anna of Denmark in 1589, and still more after his arrival in England, portraits of James continued to find their way to the continent, often proffered as gifts to his Danish and German in-laws. The royal collections in Denmark originally held a large number of his portraits as king of both Scotland and later also of England and Ireland, in addition to several of Queen Anna and the couple’s children. None of them is thought to have survived the fire that devastated Frederiksborg Castle in 1859.12 Also lost are Vanson’s miniature of James for Anna’s grandfather Ulrich III, duke of Mecklenburg, in 1601 and the painted portraits of the king, his wife, and their daughter by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger for the margrave of Brandenburg in 1611, probably on the occasion of John Sigismund’s accession.13 Another set of family portraits that cannot now be traced were conveyed to the Lithuanian magnate and James’s key Calvinist ally Janusz Radziwiłł in 1618.14 Portrait exchange was a fundamental part of early modern diplomatic culture, and all these portraits had been either gifted in response to requests or produced on the king’s initiative to accompany his ambassadors’ diplomatic missions abroad. In the same spirit, James and Anna regularly gifted their portraits and those of their children to envoys at the end of their missions, but sadly most of these have also disappeared from view.15 Where these gifts were displayed is on the whole unknown, but further research into surviving inventories could prove revealing.

12The most widely disseminated likenesses of James on the continent took the form of not paintings but engravings. Although some were created in England and made their way into continental collections through intermediaries, the majority were produced in the printmaking centres of Europe either as part of costly portrait albums or as relatively inexpensive free-standing prints sold in the open market.16 The albums were generally purchased by an educated elite of antiquaries, clerics, and noble families, and placed in their private libraries. The individual prints, judging from the inscriptions in Latin or the vernacular, were designed to appeal to literate customers who afterwards pasted them, often in sets, into books. The function of engravings, it seems, was primarily to operate as a form of visual encyclopedia.17

16The earliest free-standing prints of James were based on his depiction in other media. His likeness in Théodore de Bèze’s or Beza’s Icones, which is discussed below, had as its source the young king’s profile on a coin minted in 1575. The portrait of the adolescent James in an engraving by Jean Rabel, a court artist in Paris, is close to the painting sent to Frederick II of Denmark–Norway during the negotiations for his elder daughter’s hand (fig. 2).18 A similar painting may well have been sent to France in the mid-1580s, when there was talk of a marriage between James and Catherine de Bourbon, the sister of Henry of Navarre who was heir presumptive to the French throne. In any case, the prospect of a French marriage no doubt explains the emergence of Rabel’s portrayal of James.

18

By contrast, the image of James in two turn-of-the-century portrait albums is generic and unrecognisable, suggesting that his facial image was little known in Germany before his accession to the English throne. In both Crispijn de Passe’s Effigies regum ac principum, printed in Cologne in 1598, and the first impression of Dominicus Custos’s Atrium heroicum (figs. 3 and 4), James has a moustache and a beardless pointed chin instead of the square-cut beard evident in his 1590 marriage medal, coins of the 1590s, and portraits by Adrian Vanson.19

19

De Passe’s Effigies placed James immediately after Elizabeth I of England and before Sigismund III of Sweden and Poland–Lithuania, a positioning that may have been deliberately suggestive. After all, James had a claim to succeed Elizabeth and, if successful, would be king of a composite monarchy, just as Sigismund was. The bareheaded king is wearing pauldrons, ready to fight for his cause, and the badge of the chivalric Order of the Thistle is tied to a ribbon around his neck. Meanwhile, two lines of the verse below present him as a man of peace.20 This depiction of James was also disseminated in a free-standing print by Cornelius Pinssen the same year. The German printmaker cropped and inverted the image, removed the verse, and placed cartouches of a battle and a naval engagement respectively above and below James’s portrait.21 Although this was a frame Pinssen regularly used for portrait engravings, and hence not iconographically specific to James, the Scottish king is shown here as an unambiguously martial figure (fig. 5).22

20

Similarly accoutred with pauldrons, but this time also with a gorget and a fashionable high hat resembling the one depicted on his marriage medal, James is again portrayed as a martial prince in Custos’s Atrium heroicum. Here James, styled king of Scotland and Orkney, appears in the section on rulers holding multiple lands and positioned between Elizabeth I of England and Ireland and his brother-in-law Christian IV of Denmark and Norway. The Latin motto on James’s portrait, “Quod sis esse velis” (What thou art, thou wish to be), may refer to his hopes for England’s crown, but the Latin inscription makes no mention of that. Rather, it draws attention to James as a man of letters—“Ingenium Scotica terra tuum” (The Scottish land [exalts] thy genius)—while the verse underneath by Marcus Henning compares him to Cotys, the king praised by Ovid for his cultivated taste in literature.23

23Interest in James grew after 1603. Already renowned for his writings and his dynastic ties to the Oldenburgs, he was now a major player in European politics: the first ruler over a united Britain and successor to a queen who had warred with Catholic Spain in support of the Protestant Dutch. Besides, as a father of three, he was likely to arrange for his offspring to marry into Europe’s ruling houses. Consequently, from 1603 until his death in 1625 at least forty-five impressions of his portraits were engraved and disseminated, mainly in the Netherlands, Germany, and France. Today they are found in numerous continental museums, archives, and libraries, and in Britain in the collections of the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Galleries of Scotland, and the Royal Collection.24 Many are undated, but the dating on others reveals that they were responses to events of European significance, notably James’s accession to the English throne, his new title as king of Great Britain, and the marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to Frederick V, the Elector Palatine of the Rhine and leading prince in the reformed camp in Germany. James’s portrait also appears in several French editions of his writings.

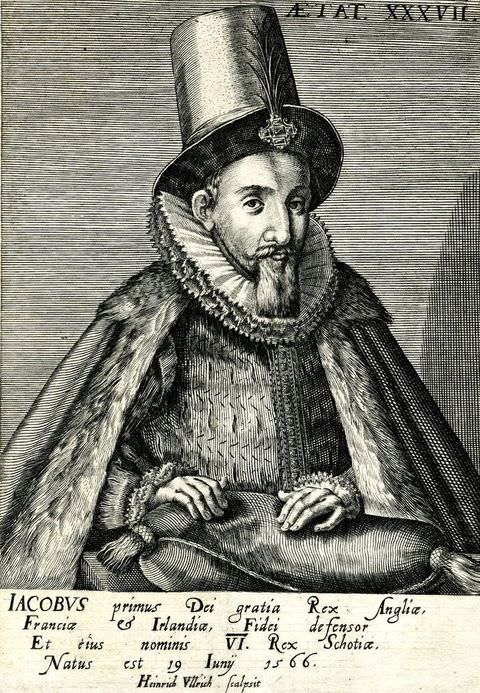

24Printmakers were quick to exploit the new market demand. Some recycled and updated earlier prints in the hope of fast profits. The workshop of Heinrich Ulrich in Nuremburg, for example, reused the image of James in rich and fashionable clothes that had previously appeared in John Jonston’s Inscriptiones historicae regum Scotorum, a poetic elegy to all Scotland’s kings, printed in Amsterdam in 1602 (fig. 6).25 The portrait is recognisably James and derives loosely from two paintings of him executed in 1595, including one attributed to Adam Vanson (fig. 7). Less successfully, the Dutch engraver Christoffel van Sichem reproduced his 1598 engraving of the Scottish king with the incorrect title of “Jacobus VI Angliae, Scotiae, et Hiberniae, Rex”. A bareheaded James is shown in full armour, which might have been taken to mean that he was ready to continue the war against Spain, a sentiment not espoused by James (fig. 8).26

25

New engravings of James were also produced abroad at this time.27 One print, now in libraries across the world, was by the Flemish engraver Pieter de Jode I, who depicted him turning slightly to the left and attired in a tall jewel-encrusted hat, a cloak trimmed with ermine, and a silk doublet, just as he appears in the 1595 painting attributed to Vanson (see fig. 7).28 That the perspective is distorted in both portraits is further evidence of the close relationship between them.29 Unusually, the paratext portrayed James as having been joyfully elected to the English throne—“Maximo applausu rex electus” (A king elected with the greatest applause), a view expressed by a number of foreign observers at the English court (fig. 9).30

27

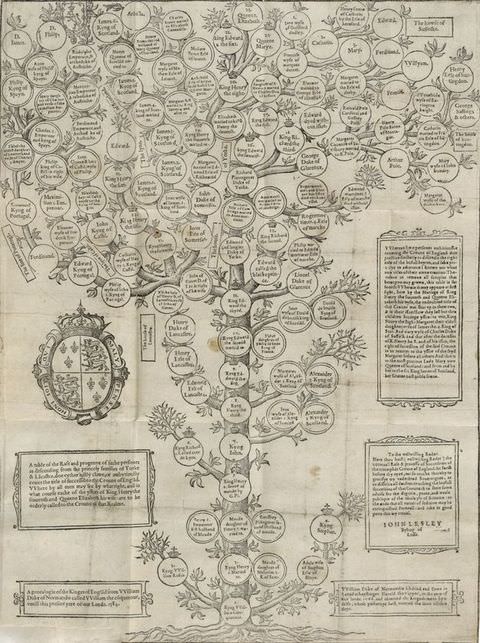

Most other engravers followed James in presenting him as a hereditary rather than an elected ruler. In a 1604 broadside executed by Jean le Clerc’s publishing house in Paris, a crowned James and Anna stand on either side of the king’s genealogical tree, with Margaret Beaufort and Edward IV at the very bottom and an oval half-length portrait of James’s firstborn and heir, Prince Henry Frederick, at its summit (fig. 10).31 The Latin text is a brief narrative of the dynastic dispute between the Lancastrians and Yorkists, as well as a description of James’s forebears and present family members. The picture itself may not have been new since it included a roundel stating the birth of James’s second daughter, Margaret, even though she had died in 1600, or possibly the engraver was ignorant of the fact. Either way, this image was repeated in several other impressions by different publishing houses, including a print engraved in the famous Claes Jansz. Visscher printing house in Amsterdam that contained a different Latin text.32

31

An anonymous double portrait of James and a young Prince Henry similarly underscored the king’s impeccable dynastic credentials. Here the engraver showed in the top margin how James and his heir were descended from the royal lines of England and Scotland (fig. 11). Wearing half-armour, James is represented as a virile martial figure who has sired a male to succeed him. Although undated, the engraving seems likely to have been produced soon after James’s accession, possibly before he assumed the title of king of Great Britain. James’s inheritance of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland is emphasised in the inscription and in the four crowns decorating the tablecloth on which his plumed helmet rests.33

33

James’s new title was proudly displayed in a short illustrated book, Regiæ Anglicæ, maiestatis pictura, et historica declaratio, published in 1604 by the de Passe printing house in Cologne in collaboration with the Arnheim printer Jan Janszoon the Elder. At the bottom of the engraving of James is a Latin inscription stressing the dynastic union of England, Ireland, and Scotland, and ending with the words “Vivite felices tanto sub Rege Britanni / Ipsius et laudes saecula quaeque canant” (Live happy Britons under so great a king, and of his praises let the ages sing). In the top corners of the plate are emblems that signify his royalty and authorial status—an open crown and sceptre to the left, and a sword and book to the right. While his clothing echoes that in the print by Pieter de Jode I, James’s face follows the pattern begun by John de Critz in 1603, so was up to date (fig. 12).34 The book also flaunts both James’s legitimacy, implicitly rejecting notions of election, and his auspicious continuation of the Stuart dynasty by opening with an engraved genealogy from Henry VII to Prince Henry Frederick (mistakenly called Prince of Wales, a title he did not acquire until 1610). The other engravings in the book are portraits of the late Queen Elizabeth, Queen Anna of Denmark, and Prince Henry. The text—in German rather than Latin—features a short biography of Elizabeth, accounts of James’s accession, the plots against him in 1603, and his merciful treatment of opponents.35

34

A new edition of this book in 1613 was timed to coincide with the marriage of James’s daughter Elizabeth to Frederick V but with a few telling changes. The family tree is no longer there, since Henry had died the previous year, while the engraving of James shows him looking older and wearing a different style of hat and collar.36 Six additional images are included, one to show James’s new heir, Charles, duke of York, and the others to draw attention to the king’s new foreign connections in Germany and the United Provinces resulting from the Palatine match.37 Incidentally a further impression of this portrait of James, now wearing a ruff and a different hat, was printed in 1622.38

36Intriguingly, the accession and later engravings of James—unlike those of his predecessor—barely reference his religion.39 Nor, in contrast to the English engraving The Papists Powder Treason of around 1612, is he shown as a providential monarch in continental prints addressing the Gunpowder Plot.40 Indeed, he barely features in them at all.41 The principal themes in all continental prints are his legitimacy, his family, his authorship, and his rule over multiple kingdoms. The Anglo-Scottish union is highlighted in several prints: an undated one by Crispijn de Passe displays ribbons with inscriptions, one of which includes the phrase “Gentem unam” (One people); another by Jacques Granthomme contains the Latin verse “Quos capit una duos tellus, Quos Insula nutrit / Una duos; unus nunc Regit hic” (Now one man rules [those] peoples, which two one land holds, which two one island).42

39While translations of the king’s works published abroad were left for the most part without a portrait of its author, three French editions of his handbook for princes, Basilikon Doron, contains an engraving of him. Unusually presenting a hatless James, the engraving had been recycled from a free-standing accession print executed by the Flemish engraver Carel van Mallery (fig. 13).43 Shortly afterwards, the French engraver Thomas de Leu inverted the image, changed James’s age, and added a new four-line verse to produce an engraving that was used in James’s 1609 anti-papal polemic Apologie and sold as a separate print; the verse flatteringly notes that in his writings the king paints himself better than any painter could (fig. 14).44

43

Throughout James’s Scottish and British reign, engravers depicted him sometimes as a man of war, sometimes as a figure ushering in peace, and occasionally both. This ambiguity reflects James’s own writings and conduct, and the changing international situation.45 In the late 1590s, the Scottish king contacted his Danish and German kin to request their assistance if he had to fight for the English throne, which may explain why he is sporting armour in German albums published at that time and in several accession engravings.46 However, since many later prints are undated, it is impossible to determine whether or not those showing him in military garb or lauding his heroic deeds were responding to particular political contexts, such as the Jülich Cleves succession dispute of 1609–10 (when James joined a military coalition in support of the Protestant candidates) or the Bohemian and Palatinate crises after 1618 (when German Protestants hoped for his military intervention).47 Similarly undated are most prints in which James is associated with peace. His smooth accession to the English throne; the dynastic union of England and Scotland, which seemingly brought an end to the hostilities between the neighbouring states; and the 1604 peace with Spain were reasons enough for this iconography. Engravers therefore included his motto “Beati Pacifici” (Blessed are the peacemakers), from Matthew 5:9, or supplementary verses extolling peace in prints in which the British king wears civilian dress. So far, we have found only one print that is specifically tied to an event. In an allegorical broadside celebrating the Twelve Years’ Truce between the Dutch Republic and Spain of 1609, James is shown leading a cart that drags the figure of War in chains (fig. 15).48

45

Although James exercised control over his visual image in England, he had no influence over that in the engravings of continental printmakers. Their commercial activities lay well beyond his jurisdiction. So, while the likenesses of the best engravers followed the face patterns of Vanson, de Critz, or Paul van Somer, the portraits of the minor craftsmen were generic and hardly a likeness at all.49 Yet, whatever their quality, they complimented James and boosted his international exposure. For most of his life, moreover, his image remained uncontested except for a brief period when he was on the cusp of adulthood, to which we now turn.

49Battle of the Books and Images

The earliest continental portraits of James are to be found in two Latin books printed two years apart, in 1578 and 1580. Their iconography and bibliographical context, we contend, epitomise a burgeoning contest over the boy-king’s persona waged by Rome and Geneva, Catholic and Protestant. This contest has been missed. The omission is due in part to scholarship’s prevailing focus on visual depictions of James produced in Britain after his accession to the English throne rather than those printed on the continent before it. Another reason has to do with the historiographic siloes related to religion. It is only by transcending these that we can reveal the efforts made by both sides of the confessional divide to claim James as one of their own and to instruct him to live up to their expectations.

The opening salvoes were delivered in John Leslie’s Latin history of Scotland De origine, moribus, et rebus gestis Scotorum and Beza’s Icones a collection of emblems twinned with portraits of European reformers and other worthies.50 The former was printed in Rome and the latter in Geneva. Leslie, Scottish Catholic bishop of Ross, Stewart loyalist, and diplomatic agent and publicist-in-chief of the captive Mary, Queen of Scots, dedicated his book to Pope Gregory XIII, while Beza, a Monarchomach, reformist preacher, and Calvin’s successor as president of the Company of Pastors in Geneva, inscribed his to James VI of Scotland. There is a transnational backstory to be told about the likenesses of James in Leslie’s and Beza’s books; both would go on to have a hitherto underexplored afterlife.

50No stranger to controversy, Bishop Leslie had previously defended the title of his queen in two separate editions of a substantial succession tract.51 In 1569 Leslie, masquerading as an Englishman, denounced Mary’s deposition from her Scottish throne as illegal and asserted her hereditary right to succeed the childless Elizabeth on the English one. In the second version, swiftly revised in 1570 after the papal excommunication of Elizabeth, Leslie demoted her from queen to governor. His embroilment in the Ridolfi plot in 1571 earned him a three-year spell in jail: petrified of torture, he confessed his involvement and grovelled before being granted permission to go into exile on the continent. There, he soon resumed his labours on behalf of Queen Mary, who was casting about for a way to regain a modicum of political agency. The scheme she lit on, and which Leslie would passionately promote, was to become joint sovereign with her son in the Crown of Scotland. Known as the Association, the project would naturally require James’s consent but Elizabeth too would have to approve it.52 Mary hoped her son, whom at her request Catholic powers had so far refused to recognise as king, might be amenable to some such arrangement now that he was coming of age. Before officially broaching the terms of the Association with the parties concerned, Mary had Leslie embark on a tour of European courts to take soundings and rally support for her cause.

51The publication of Leslie’s imposing Latin history of Scotland was meant to assist if not launch that campaign. The bishop had already written a partial account of Scottish history in Scots in 1569–70 that he presented to his queen, and would soon compose the Relatio, a succinct Latin summary of the period 1542–78, at the request of Emperor Rudolf, whose court in Prague he visited in 1578 and to whom he also gave portraits of the Stewart mère et fils.53 Both the history in Scots and the Relatio were destined to remain in manuscript, although the latter would circulate widely in scribal copies. De moribus, incorporating a Latin redaction of the previous Scots text, and equipped with ornate paratextual apparatus and illustrations, sought first and foremost to broadcast a legitimist version of Scottish history, stressing the Stewarts’ impeccable dynastic credentials and their enduring fidelity to the Catholic faith.

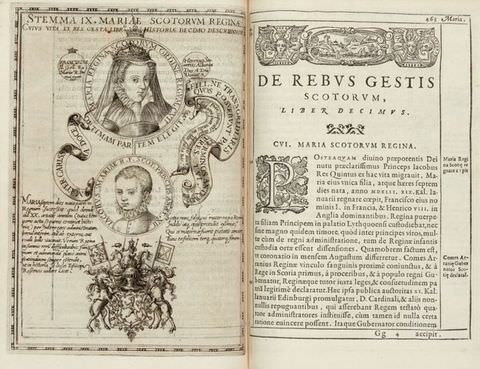

53But the book’s subtler polemical goal was to adumbrate the Association scheme which as yet remained under wraps. It is for this reason that, instead of using an image solely of his royal mistress, Leslie inserted a suggestive double portrait of Mary and James, whose iconography, together with the adjacent text, reminded the international audience of both the illegality of the Scottish queen’s deposition and the priority of her claim to England’s throne over that of her son (fig. 16). The likeness of Mary, with a crown on her head, labelled “Scotorum Regina”, is larger than and positioned above that of bareheaded James, labelled “Scotorum princeps”; this is also how Leslie pointedly differentiates between mother and son throughout De moribus. Prefacing book 10, which chronicled Mary’s reign up to 1562, this double image held several messages for several addressees. It simultaneously aimed to convince potential allies and inveterate enemies alike that the Stewart mother and son were at one, not least in their religious commitments—Mary is shown catechising her son from afar and nudging James, now on the threshold of adulthood, to make common cause with his mother and embrace the true faith to obtain recognition as king and safeguard his title to the English succession. The book is listed in the inventory of James’s library.54

54

Coinciding with the termination of the earl of Morton’s regency in March 1578, Leslie’s De moribus and his diplomatic offensive could not go unanswered.55 Reformers in Scotland and elsewhere grew ever more alarmed that, despite his rigorous godly education, overseen by the formidable humanist scholar, fervent reformer, and Mary’s implacable enemy George Buchanan, James might yet betray the hopes vested in him. As well as frantic behind-the-scenes manoeuvres, there ensued a veritable battle of the books and, with it, a battle of images. At stake were not only the younger Stewart’s confessional allegiance and the political course that might spell for Scotland but also true religion’s future within Britain and Ireland.

55James had been brought up under the stern tutelage of the committed reformers Buchanan and Peter Young, but would he remain constant to the faith? Might he be seduced by the siren voices of his mother’s emissaries and sacrifice his immortal soul for the worldly prize of England’s crown, never mind having his Scottish kingship reaffirmed? What if he were to reconcile with both his wicked mother and the Romish Antichrist, and in the fullness of time unite the archipelago under his apostate sceptre? Little wonder that, within a year of De moribus, the septuagenarian Buchanan brought out an edition of his De iure regni apud Scotos, a Latin resistance tract drafted in the later 1560s to justify Mary’s overthrow but until now withheld from print.56 This cast Scotland as an elective monarchy where evil princes had been and would continue to be duly removed by the people. A resounding apologia for popular sovereignty, and implicitly a riposte to Leslie’s history, De iure was framed as a harsh sermon for its royal dedicatee. At this watershed moment in his life, the thirteen-year-old James was being publicly warned not to swerve from the path of virtue lest he be made to share the fate of his wayward mother.57

56Neither Buchanan’s De iure nor Leslie’s De titulo et iure serenissimae principis Mariae Scotorum reginae, a Latin recension of his earlier succession tract now doubling up as a rejoinder to Buchanan, featured a portrait of James. In high demand on the continent, De titulo, complete with a fold-out genealogical tree parading the Stewart line’s dynastic prowess and again insinuating a close entente between the Scottish queen and her son, caused quite a stir.58 Meanwhile, the anxieties of reformers at home and abroad had been further exacerbated by the arrival in Scotland in September 1579, and vertiginous rise in royal favour, of James’s Catholic cousin Esmé Stewart, sieur d’Aubigny (shortly ennobled as earl and then duke of Lennox), who had been seen off by Leslie. It is in these circumstances that what might seem no more than a paper war between two elderly Scottish ideologues elicited a contribution from one of Europe’s greatest living reformed theologians and political thinkers, Theodore Beza. Following the example of his friend and ally Buchanan, Beza dedicated his labours to the then fourteen-year-old Scottish king. More to the point, he prefixed to the book a frontispiece with a specially commissioned likeness of James.

58As its title implies, Beza’s Icones, id est verae imagines virorum doctrina simul et pietate illustrium was not about Scottish religious politics. Its remit was at once more ambitious and less overtly polemical: to create a European pantheon of virtuous and pious men through both text and image, that is, versified encomia and woodcut portraits (though in the event not everyone’s likeness had been sourced in time).59 While most of those selected for inclusion (for example, Calvin, Knox, and Buchanan) professed the reformed religion, there were also some outliers, if not exactly honorary Protestants, such as Erasmus of Rotterdam and the French chancellor Michel de l’Hôpital. Nonetheless, what emerged from Icones was a strong sense of the Protestant international, with a few good people from across the confessional divide thrown in.

59Why accord such prominence to an adolescent from far-off Scotland? What clues can we glean from the iconography of James’s portrait and the tenor of Beza’s address? The standard explanation emphasising close links between Genevan and Scottish Protestants tells but half the story. Most modern commentators fail to register either the fragility of Scotland’s Protestant regime at this time or the simple fact that James’s kingship was disputed.60 The crux, we suggest, is that, as James approached his majority and the regency government came to an end, the contest for his heart and mind began in earnest. Images were an integral part of it.

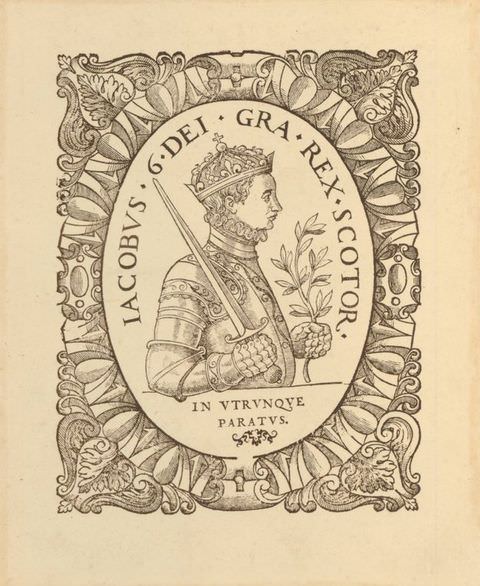

60The woodcut portrait in Beza’s book emphasises James’s providential royalty (fig. 17). Depicted in profile, he is wearing a closed imperial crown and the text identifies him as “Jacobus.6.Dei.Gra.Rex.Scotor.” (by the grace of God, King of the Scots). Rather than orb and sceptre, James is shown holding a sword and an olive branch; the Virgilian motto below, “in utrunque paratum” (sic), signifies that he is ready (prepared) for either war or peace. Yet the military aspect is unquestionably dominant, for the boy-king is clad in armour. The picture thus turns Scotland’s monarch into an emblem of sorts. Its iconography, however, was hardly original.

In preparing the woodcut for Beza’s book, the unnamed artist used as his model a £20 gold coin issued in Scotland in 1575 to mark the King’s Party’s victory over the forces loyal to Queen Mary. It was the first coinage of James’s reign to have an image of him. Whoever made the portrait of James for Icones closely copied that on the obverse or front of the Scottish coin, which was itself inspired by George Buchanan’s epigram addressed to the English diplomat Thomas Randolph as well as by the French Catholic Claude Paradin’s influential emblem book, Devises heroïques.61 The Jacobean coinage replaced Paradin’s trowel with an olive branch, adding a Virgilian maxim as per Buchanan, and the woodcut-maker followed suit.

61The numismatic pedigree of James’s portrait in Beza’s Icones is well known. What has not been properly explained is why the radical continental reformer decided to dedicate the book to the fourteen-year-old James in the first place and why he commissioned this particular image to accompany his part-laudatory, part-didactic Latin address. Why not, for example, honour the Huguenot champion Henry of Navarre, narrow escapee from the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre? Certainly, with its combination of words and images, Icones was intended to shape public opinion across the continent; the swift printing the following year, in 1581, of a French translation by the Genevan reformer Simon Goulart amply attests to the book’s intended reach—even if, in the event, its impact proved less than expected.62

62Beza’s dedication exalts James’s learning and piety, instilled in him by Buchanan and Young and, in a neat instance of laudando praecipere, foretells that the king will surpass earlier monarchs in godliness and virtue.63 Yet Beza’s epistle is more than a conventional application of the trope of teaching through praise. With its catalogue of Scottish (and one English) reformed apologists for resistance—Buchanan, Knox, Goodman—Beza implicitly warns the king against confessional backsliding. Tellingly, Beza’s eulogy of Buchanan comes a mere year after the publication of De iure regni apud Scotos in Edinburgh, and in the very year the second edition was issued in London. (James reviled De iure so much that in 1584 the Scottish Parliament banned it at his behest.64) By comparison with Buchanan’s monitory address to his charge, Beza’s dedication appears at once more courteous and more hopeful, mapping out a bold international career for the Scottish royal. In their various ways, both men remind the young king of his duty. Buchanan threatens that failure on James’s part will be punished by deposition; Beza works to inspire him to do good with a prospect of universal admiration and, without so much as breathing a word about the English succession, tacitly confers on James the mantle of the future militant Protestant monarch of Britain and Ireland, and potentially leader of reformers across Western Christendom. Beza’s textual and pictorial intervention set forth a powerful counter-image to that of a weak and childlike prince dependent on his mother’s say-so we saw in Leslie’s De moribus. Before long, Mary and Leslie too realised that gratifying James’s sense of pride and self-worth might be the better course: in 1584, in the new English edition of Leslie’s succession tract, James is hailed as Scotland’s king alongside his mother-queen in an engraved double image hinting that the Association is now a fait accompli (fig. 18).65 This episode proved not just short-lived but unique: never again would Protestants and Catholics deploy James’s visual image to enlist him as one of their own. Henceforth, both confessions relied only on words.

63

Promoting the Oldenburg–Stewart Alliance in Denmark–Norway

The circulation of visual images of James in Denmark–Norway spiked after his marriage to Anna and extended sojourn there, and again following the royal couple’s ensconcement in their new kingdom. Some portraits were personally gifted to ambassadors and diplomats by James and Anna, while others were actively sought out by the Danish court.66 As early as 1597, a year after his coronation, Christian IV asked James for portraits of himself and his family.67 Whether or not James obliged, Christian’s desire to obtain portraits of his brother-in-law is a testimony of the latter’s growing international stature and the desire of both monarchs to promote the Oldenburg–Stewart alliance through visual images.

66In the late 1580s James pursued stronger diplomatic ties with Europe’s foremost Protestant states.68 A turning point came with the Scoto-Danish match in the summer of 1589. Marriage had been first broached in 1585, when Frederick II despatched an embassy to Scotland to discuss the thorny legal status of Orkney and Shetland.69 As part of the negotiations, a portrait of James painted by Adrian Vanson was probably sent to Denmark in 1586 (see fig. 1). The German inscription “James der Sechst—Konnig Von Schottlandi” (James the Sixth—King of Scotland) suggests as much, since German was one of the languages spoken at Frederick’s court. Furthermore, since Frederick had insisted on viewing a portrait of his own potential bride during the 1560s and 1570s, it was almost certain that he would demand to see James’s likeness when considering a match for his daughter. Negotiations, however, soon reached a stalemate because of disagreements about the ownership of the Northern Isles, and a breakthrough came only after Frederick’s death in 1588.70

68From James’s perspective, the marriage with Anna was attractive, because she came from a Protestant family firmly allied to the chief Lutheran courts in the Holy Roman Empire. Throughout the 1590s, James sought to take advantage of the Oldenburg kinship network by forging closer relations with leading German Protestants. In working to build a Protestant coalition consisting of Scotland, Denmark–Norway, and German states, James’s aim was twofold: to secure peace in the Netherlands and to drum up support for his claim to the throne of England.71 For the Danes, James’s position as Elizabeth’s likely heir was too good an opportunity to let slip, and it paid off after 1603, when the Danish alliance with Great Britain became the cornerstone of Christian IV’s foreign policy.72

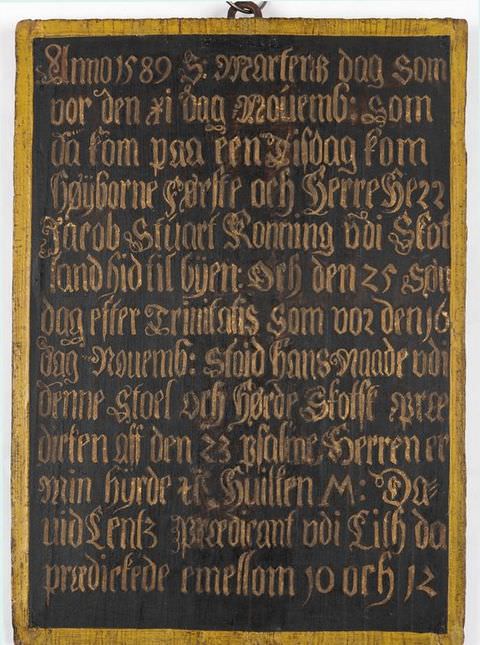

71Anna and James were married by proxy in August 1589 and, after her unsuccessful attempt to cross the stormy North Sea in early September, James resolved to sail to Norway in early October to fetch his young bride. The escapade garnered considerable publicity not just in Denmark–Norway and Scotland but elsewhere too. One of the few visual traces that remain of James’s impromptu continental voyage and the royal couple’s subsequent honeymoon is an oaken tablet commemorating James’s visit to the Mariakirke in Tønsberg in November 1589, when he was en route to Oslo to meet his new wife (fig. 19).73 The inscription on the tablet is in Danish and the translation reads:

73The year 1589: On Saint Martin’s day which was the 11th day of November, which then fell on a Tuesday, came the highborn master and lord, Jacob Stewart, King of Scotland, to this town, and the 25th Sunday after Trinity Sunday, which was the 16th day of November, his grace sat in this pew and heard a Scottish sermon on the 23 psalm “the Lord is my shepherd” by Mr. David Lentz [Lindsay], preacher in Lith [Leith], who preached between 10 and 12.

Although we do not know who commissioned or made the tablet, its swift installation to commemorate James’s visit is itself rather remarkable and testifies to his developing reputation outside Scotland.

After crossing the Øresund in early 1590, James made good use of his time in Denmark, turning his improvised honeymoon into a public relations coup. The Scottish king called on the renowned astronomer Tycho Brahe, with whom his tutors Peter Young and George Buchanan had corresponded in the 1570s, in his observatory Uraniborg on the island of Ven; visited the University of Copenhagen; and travelled to Roskilde to discuss theological matters with the distinguished Lutheran divine Niels Hemmingsen.74 At Kronborg Castle, James attended the wedding of Anna’s elder sister, Elisabeth, to Heinrich Julius of Brunswick–Lüneburg, and got to know Duke Ulrich of Mecklenburg, Anna’s maternal grandfather. During his time in Denmark–Norway, James thus met the intellectual luminaries of the kingdom and, more importantly, was able to foster personal relations with Protestant leaders that he would later exploit.

74In addition to its political significance, the Stewart–Oldenburg match ushered in a period of dynamic cultural exchange between Britain and Denmark–Norway that lasted well into the Caroline period. A vital dimension of this process was the transfer of visual images and the movement of artists between London and Copenhagen.75 Besides the wealth of engravings by Simon and Crispijn de Passe, Thomas de Leu, Ronald Elstrack, and Pieter de Jode I that are well represented elsewhere in Europe, Danish royal collections also held a large number of portraits of James as king of Scotland, and later also of England and Ireland, alongside several portraits of Anna of Denmark and the couple’s children.76

75Although most of the British portraits perished in the fire of 1859, it is possible to retrieve a sense of the original collection from a couple of sources. The most important is the writings of the Danish art historian Niels Laurits Høyen, who catalogued the portrait collection in the early 1830s. Høyen’s posthumously published description of Frederiksborg Castle indicated that there were twelve portraits of James and his family there before 1859.77 He mentions “an excellent work” by Daniel Mytens, several portraits by van Somer, a portrait of Elizabeth Stewart by Gerard van Honthorst, and a portrait of Anna in her “33rd year wearing an exquisite pearl embroidered garment” painted by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger.78 Høyen’s dating is, however incorrect: Anna was thirty-three in 1607, and the earliest known portrait of Anna by Gheeraerts dates from 1609.79

77Høyen’s catalogue identifies two portraits of James: one by an unnamed artist and the other, painted on panel, most likely by John de Critz or his workshop.80 The latter portrait was copied by the Danish painter Frederik Christian Lund in 1858, and the drawing shows James in three-quarters length wearing a hat with “The Feather” jewel (fig. 20). Around his neck, the king wears a chain with the badge of the Order of the Garter. Although the exact provenance of the original is uncertain, the drawing is very similar to another portrait of James attributed to de Critz (fig. 21).81 Other portraits of James by de Critz were sent to Austria, Lorraine, Germany, and Tuscany after 1603, so it is likely that James also sent a portrait of himself to Denmark–Norway.82 Additionally, three miniatures of James, Anna, and Prince Henry, made around 1605 by Nicholas Hilliard, were gifted to Christian by his brother-in-law (fig. 22).83

80

The English author Horace Marryat, who visited Denmark in 1858, identified three portraits of James at Frederiksborg Castle in his published travelogue. One portrayed James “in the costume of the period, his head capped by a beret, a sickly frightened boy of some twelve years old, such as you may have imagined him to be—well flogged by the Puritan birch of Buchanan, and snubbed by cross old Lady Mar”.84 Marryat further mentioned a portrait of James by Paul van Somer and described “a copy sent over to Denmark—a half-length—in a white dress; perhaps the most characteristic of the three: he is now an aged man, with a discontented sawny expression of countenance, most unprepossessing”.85 However, the provenance and authorship of the portraits are unknown.

84The number and range of oil portraits of James known to have been held in Denmark–Norway attest to their importance in bolstering the Oldenburg–Stewart alliance. So do the engravings of James housed in the Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle, the National Gallery of Denmark, and the Royal Library of Denmark.

Conclusion

This article has charted the European circulation of James’s images in his lifetime, explaining their ideological and commercial ramifications. Depictions of the king, as we have seen, took a range of forms, from miniatures and full-length portraits to woodcuts and engravings. Their purpose and intended use were also diverse. Made in Scotland, and later in England, at royal behest, portraits and miniatures served as diplomatic gifts. They underlined the care James took in cultivating his visual brand and, through it, promoting the Stuart dynasty.

Whether free-standing or inserted into printed compendia on kings and queens, engravings, mainly by Dutch, German, and French artists, fed the international curiosity about and appetite for the king’s likenesses. Some showed James with his family, emphasising his dynastic prowess; others hailed him as a man of letters; still others presented him as a warrior, a Rex Pacificus, or both. Yet, except for a brief interval between 1580 and 1584, when engraved images of the teenage king fuelled a cross-confessional contest over his—and Scotland’s and England’s—future, James’s visualisations did not court controversy. Rather, they bear witness to how this son of a deposed and executed queen and a murdered father carved an auspicious career for himself through an astute dynastic match and savvy political manoeuvring that won him the crowns of the three kingdoms.

What sets James apart from both his Scottish and his English predecessors is the tremendous number of engraved images of him produced and disseminated on the continent. Who knows what else lurks in some of the European courts, archives, and art collections.

Acknowledgements

For conversation and advice, we are grateful to Bjørn Bandlien, Peter Davidson, Elizabeth Goldring, Poul Grinder-Hansen, Patrick Kragelund, Hanna Mazheika, Jane Stevenson, and Mara Wade. Christopher Archibald has provided invaluable help with the Latin. Paulina Kewes also wishes to acknowledge the support of the Leverhulme Trust, which awarded her a major research fellowship (2021–24) for the project “Contesting the Royal Succession in Reformation England: Latimer to Shakespeare”. David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt wishes to thank Hans Fabricius-Rahbek and Anna Nørrekjær Sørensen at the Museum of National History, and the Independent Research Fund Denmark, for funding the project “Crossing the North Sea: Anna of Denmark and British–Danish Cultural Exchange in the Early Modern Period” (2024–26).

About the authors

-

David Hasberg Zirak-Schmidt is a postdoc in comparative literature at the University of Southern Denmark and Queen Mary University of London specialising in early modern literature and drama. His research interests include gender, court performance, festival culture in Scandinavia and Britain, the intersections between political theory and literature, and historical drama. He has published articles about Jacobean and Caroline playwrights, the English history play, the iconography of the Eikon Basilike, and the political aspects of Caroline literature. He is currently working on a postdoctoral project, funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark, examining the cultural agency of Anna of Denmark and Danish–British cultural exchange in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

-

Paulina Kewes is Professor of English Literature and Fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. She has published widely on early modern literature, history, and political thought. She is completing a book entitled Contesting the Royal Succession in Reformation England: Pole to Shakespeare for Oxford University Press, which has been supported by a Leverhulme Trust Major Research Fellowship (2021–24), and leads an international, interdisciplinary project on parliamentary culture in the early modern world.

-

Susan Doran is Professor of Early Modern British History at the University of Oxford and Senior Research Fellow at Jesus College, Oxford. She has published extensively on the Tudors and edited four catalogues of major exhibitions held in London. Her most recent book is From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Footnotes

-

1

See Larry Silver, Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008). ↩︎

-

2

Fernando Checa Cremades, Carlos V: La imagen del poder en el Renacimiento (Madrid: El Viso, 1999). ↩︎

-

3

Laura Fernández-González, Philip II of Spain and the Architecture of Empire (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021), esp. chs. 3–4. For images celebrating the marriage between Philip and Mary, see Alexander Samson, Mary and Philip: The Marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 210–11. ↩︎

-

4

Steffen Heiberg, Christian 4: En europæisk statsmand (Copenhagen: Lindhardt & Ringhof, 2017), 433. For the political use of Christian’s portrait, see Lars Olof Larsson, “Rhetoric and Authenticity in the Portraits of King Christian IV of Denmark”, Daphnis 32 (2003): 13–40. ↩︎

-

5

See Kate Anderson, Art & Court of James VI & I: Bright Star of the North (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025), exhibition catalogue; Elizabeth Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), 251–52; Roy Strong, Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, 2 vols. (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1969); and Arthur M. Hind, Engraving in England in the Sixteenth & Seventeenth Centuries: A Descriptive Catalogue with Introductions, vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969). ↩︎

-

6

Astrid Stilma, A King Translated: The Writings of King James VI & I and Their Interpretation in the Low Countries, 1593–1603 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012). ↩︎

-

7

Cynthia Fry, “Diplomacy & Deception: King James VI of Scotland’s Foreign Relations with Europe, c.1584–1603” (PhD thesis, University of St. Andrews, 2014); Steven J. Reid, The Early Life of James VI: A Long Apprenticeship, 1566–1585 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023); Alexander Courtney, James VI, Britannic Prince: King of Scots and Elizabeth’s Heir, 1566–1603 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2024). ↩︎

-

8

See Susan Doran, From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024), esp. 430–64. ↩︎

-

9

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 9379; Museo Nacional de Prado, Madrid, P001954; Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 3569; Palazzo Pitti, Florence, 1890, 3568; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-4390 and SK-A-4302; and Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMGrh 816. ↩︎

-

10

Duncan Thomson, “Vanson, Adrian [Son, Adriaen van]”, in The Grove Encyclopedia of Northern Renaissance Art, ed. Gordon Campbell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/acref/9780195334661.001.0001/acref-9780195334661-e-1902. ↩︎

-

11

Rijksmuseum, SK-A-4390 and SK-A-4302. ↩︎

-

12

Stefan Pajung, Dansk–Engelsk Portrætkunst (Hillerød: Det National Historiske Museum, 2022), 18. ↩︎

-

13

Thomson, “Vanson, Adrian”; Karen Hearn, Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, 1530–1630 (London: Tate, 1995), 192. ↩︎

-

14

Catherine MacLeod, “Facing Europe: The Portraiture of Anne of Denmark (1574–1619)”, in Telling Objects: Contextualizing the Role of the Consort in Early Modern Europe, ed. Jill Bepler and Svante Norrhem (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2018), 78; Hanna Mazheika, "From Text to Network: Confessional Contacts and Cultural Exchange between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Britain, ca 1560s–1660s (PhD diss., University of Aberdeen, 2019), 88–94. ↩︎

-

15

Tracey A. Sowerby, “Negotiating the Royal Image: Portrait Exchanges in Elizabethan and Early Stuart Diplomacy”, in Early Modern Exchanges: Dialogues between Nations and Cultures, 1550–1800, ed. Helen Hackett (London: Routledge, 2016), 120–21. ↩︎

-

16

Prints by Simon and Willem de Passe (then working in England) and Francis Delaram can be found in Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum (HAUM), Braunschweig; Royal Library of Denmark, Collection of Prints and Photographs, Müllers Pinakotek; and National Gallery of Denmark. ↩︎

-

17

Peter Parshall, “Prints as Objects of Consumption in Early Modern Europe”, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 28, no. 1 (1998): 24, 27–28. ↩︎

-

18

Copies of the engraving are in Musée National du Château de Pau and Princeton University Art Museum. For the marriage negotiations, see Courtney, James VI, 105–6. ↩︎

-

19

Dominicus Custos, Atrium heroicum. Caesarum, regu[m], aliarumque summatum, ac procerum. Qui intra proximum seculum vixere, aut hodie supersunt (Augsburg: Custos, 1600). In the second impression, James is bearded. British Museum (BM), 1873,0510.2788 and 1873,0510.2736. ↩︎

-

20

Individual prints can be found in the Biblioteca Nacional de Espagña; the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris (BnF), ark:/12148/cb415012577; and elsewhere. De Passe’s book contains eighteen portraits, including two others of English interest, those of Thomas Cavendish and Sir Francis Drake. ↩︎

-

21

Royal Collection, RCIN 601295. ↩︎

-

22

A similar background exists for engravings of Andreas, cardinal of the Holy Roman Empire, and Margaret of Austria, queen of Spain and Portugal, among others. ↩︎

-

23

Custos, Atrium heroicum, part 1. The British Museum print of James VI from this book (1873,0510.2788) was bought from a Leipzig dealer. See also Royal Collection, RCIN 601299; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1951.11.932, 1951.11.934. ↩︎

-

24

Those in the Royal Collection were originally in the collection of Cassiano dal Pozzo, sold by Cardinal Alessandro Albani in 1762 to George III. ↩︎

-

25

Prints can be found in the La Salle University Art Museum; the National Galleries of Scotland; and the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), London. ↩︎

-

26

HAUM, CvdaeSichem AB 3.50; BM, 1868,0822.2405; Biblioteca Nacional de España; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. ↩︎

-

27

See, for example, prints by Carel (or Karel) van Mallery, Jacques Granthomme, and Jacques de Fornazeris. ↩︎

-

28

Royal Library of Denmark, Müllers Pinakotek, 2, 80, I, 4^o^; PR Real Biblioteca Signatura Topográfica, VIII/M/19 (182); NPG, D25684 and D18177; National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, PG 156; Royal Collection, RCIN 601305; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 17.3.756.1779 and 17.3.756.1104; HAUM, PdJodedAe AB 3.43. ↩︎

-

29

Duncan Thomson, Painting in Scotland, 1570–1650 (Edinburgh: Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1575), 30. ↩︎

-

30

For the significance, see Doran, From Tudor to Stuart, 99–103. ↩︎

-

31

BM, 1974,1207.6. Cut-down versions are in Herzog August Bibliothek (HAB), Wolfenbüttel, A 5883; and Royal Collection, RCIN 601406; Royal Library of Denmark, Müllers Pinakotek, 2, 79, 4^o^, ref. F.259. ↩︎

-

32

For the Visscher, see BM, 1935,0413.82. See also other similar prints: Royal Library of Denmark, Müllers Pinakotek, 2, 79, 4^o^, ref. F.259; Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung, Vienna, PORT_00067523_01; NPG, D18233 and D20238; BM, 1848,0212.76. ↩︎

-

33

HAUM, P-Slg AB 3.1951; Royal Library of Denmark, Müllers Pinakotek, 2, 81 a, 2°; BM, 1864,0813.101. ↩︎

-

34

The engraving of James in Regiæ Anglicæ maiestatis pictura is in NPG, D18173; and Royal Library of Denmark, Müllers Pinakotek, 2, 77, III, 8^o^. ↩︎

-

35

Ilja M. Veldman, Crispijn de Passe and His Progeny (1564–1670): A Century of Print Production (Rotterdam: Sound & Vision, 2001), 154–55. ↩︎

-

36

A plate of this second impression can be found in the National Gallery of Denmark, KKS2027, and in Frederiksborg Castle, as well as in BM, O,8.155; Royal Collection, RCIN 601318; and NPG, D18173. ↩︎

-

37

Princess Elizabeth as electress of the Palatine, her husband, her parents-in-law, and Count Maurice of Nassau-Orange. Hind, Engraving in England, 2:40–41. ↩︎

-

38

HAUM, CdPasse d.A.AB 3.355. ↩︎

-

39

James, however, is one of the princes depicted in the 1614 allegorical painting Fishing for Souls by Adriaen Pietersz van de Venne, now in the Rijksmuseum, which illustrates the confessional division of Europe. Anderson et al., Art and Court, 23–24. ↩︎

-

40

Alexandra Walsham, Providence in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 256; Hind, Engraving, 2:394–95. ↩︎

-

41

One of the three parts of an anonymous engraving dated about 1623 depicts James in Parliament above Guy Fawkes being led by the devil to the vault below. BM, 1851,0308.736. ↩︎

-

42

HAUM, JGranthomme AB 3.23; BM, 1848,0911.267; NPG, D18254. ↩︎

-

43

For the print see BM, 1871,1209.907. The portrait appears in the copies of Basilikon Doron printed by Guillaume Avray in Paris in 1603 and 1604, and by Thomas Daré in Rouen in 1604. For details of the editions, see James Craigie, ed., The Basilicon Doron of King James VI (Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1950), 161, 166, 167–68. There are some later miniatures of a hatless James but very few engravings or medals. Helen Farquhar, Portraiture of Our Stuart Monarchs on Their Coins and Medals (London: Harrison & Sons, 1917), 158–59. ↩︎

-

44

James I, Apologie pour le serment de fidelite que le serenissime Roy de la Grand’ Bretagne requiert de tous ses sujets, tant ecclesiastiques que seculiers (London: Jean Norton, 1609). The print is now in BnF Gallica, https://numelyo.bm-lyon.fr/f_view/BML:BML_00GOO0100137001101618127; National Gallery of Denmark; Philadelphia Art Museum; BM; Royal Collection; and NPG. ↩︎

-

45

For an exploration of early modern discourses on peace and James’s dilemmas, see Noah Millstone, “Rex Pacificus and the Short Peace, 1598–1625”, in James VI and I, ed. Alexander Courtney and Michael Questier (London: Routledge, 2025), 168–99. ↩︎

-

46

In addition to those already mentioned, see HAUM, JGranthomme AB 3.23; and BM, 1864,0813.99. ↩︎

-

47

These prints include Royal Collection, RCIN 601397; BM, 0,8.158; and NPG, D18262. ↩︎

-

48

The whole engraving, attributed to David Vinckboons, is in the Rijksmuseum. A fragment focusing on James attributed to Hessel Gerritsz is in the Royal Collection, RCIN 601412. ↩︎

-

49

Royal Library of Denmark, Müllers Pinakotek, 2, 77, I a, 8^o^; NPG, D1825; BM, 1864,0813.102 and 1864,0813.99; Royal Collection, RCIN 601307. ↩︎

-

50

John Leslie, De origine, moribus, et rebus gestis Scotorum, libri decem (Rome: Stamperia del Popolo Romano, 1578); Beza, Icones, id est verae imagines virorum doctrina simul et pietate illustrium (Geneva: Jean de Laon, 1580). ↩︎

-

51

Leslie, The Defence of the Honour of Right Highe Mighty and Noble Princesse Marie Queene of Scotlande and Dowager of France (London [Rheims]: Eusebius Dicæophile, 1569); A Treatise concerning the Defence of the Honour of the Right, High, Mightie aand Noble Princesse, Marie Queene of Scotland, and Douager of France (Leuven: Gualterum Morberium [and J. Fowler], 1570). For Leslie’s life and writings, see D. M. Lockie, “The Political Career of the Bishop of Ross, 1568–80”, University of Birmingham Historical Journal 4 (1954), 98–145; Margaret J. Beckett, “The Political Works of John Lesley, Bishop of Ross” (PhD thesis, University of St. Andrews, 2002); Tricia A. McElroy, “Executing Mary Queen of Scots: Strategies of Representation in Early Modern Scotland” (PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 2004). ↩︎

-

52

So far, the only account of the Association is Susan Doran and Paulina Kewes, “Joint Iconography for Joint Sovereigns: Mary Queen of Scots, James VI of Scotland, and the Campaign for Association, c. 1578–1584”, in Women and Cultures of Portraiture in the British Literary Renaissance, ed. Yasmin Arshad and Chris Laoutaris (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2025), 49–68. ↩︎

-

53

The portraits have not survived. The text of Leslie’s “De statu Reginae Scotiae Principis ejus filii et totius Regni brevis narratio ab anno 1542 usque ad 78” can be found in Lockie, “Political Career”, appendix 1, 138–45. ↩︎

-

54

De origine appears alongside Buchanan’s De iure. See George F. Warner (ed.), The Library of James VI, in Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, 1st series, vol. 15 (Edinburgh: Scottish History Society, 1893), xxxvi, xxxvii. ↩︎

-

55

Amy Blakeway, “James VI and James Douglas, Earl of Morton”, in James VI and Noble Power in Scotland, 1578–1603, ed. Miles Kerr-Peterson and Steven J. Reid (London: Routledge, 2017), 12–31. ↩︎

-

56

George Buchanan, De iure regni apud Scotos, Dialogus (Edinburgh: I. Rosseum for H. Charteris, 1579); Roger A. Mason and Martin S. Smith, eds., A Dialogue on the Law of Kingship among the Scots: A Critical Edition and Translation of George Buchanan’s “De Iure Regni apud Scotos Dialogus” (London: Routledge, 2004). ↩︎

-

57

Mason and Smith, A Dialogue, 2–3. In the year of his death, Buchanan’s own Latin history of Scotland setting the record straight vis-à-vis Leslie’s De origine was printed with yet another monitory dedication to James and a flurry of poems commending the sage author and lecturing the young king by the Calvinist divine Andrew Melville and other godly Scots. See George Buchanan, Rerum Scoticarum historia (Edinburgh: Alexander Arbuthnot, 1582), sigs.2r–4r. ↩︎

-

58

Doran and Kewes, “Joint Iconography”, 57–59. ↩︎

-

59

Alison Adams, “The Emblemata of Théodore de Bèze (1580)”, in Mundus Emblematicus: Studies in Neo-Latin Emblem Books, ed. Karl A. E. Enenkel and Arnoud S. Q. Visser (Turnhout: Brill, 2003), 71–99; E. J. Hutchinson, “Written Monuments: Beza’s Icones as Testament to and Program for Reformist Humanism”, in Beyond Calvin: Essays on the Diversity of the Reformed Tradition, ed. W. Bradford Littlejohn and Jonathan Tomes (Lincoln, NE: Davenant Trust, 2017), 21–61. ↩︎

-

60

Adams, “Emblemata”; Hutchinson, “Written Monuments”; Michael Bath and Theo van Heijnsbergen, “Paradin Politicized: Some New Sources for Scottish Paintings”, Emblematica 22 (2016): 43–67. ↩︎

-

61

Claude Paradin, Devises heroïques (Lyon: Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau, 1551; expanded 1557); Ian Stewart, “Coinage and Propaganda: An Interpretation of the Coin Types of James VI”, in From the Stone-Age to the Forty-Five, ed. Anne O’Connor and D. V. Clarke (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1983), 451, 455; Bath and van Heijnsbergen, “Paradin Politicized”, 47–48. ↩︎

-

62

Beza, Les vrais pourtraits des hommes illustres en pieté et doctrine, trans. Simon Goulart (Geneva: Jean de Laon, 1581). The French version contained a number of alterations and additional images. ↩︎

-

63

Beza, Icones, sigs. ii.r–iii.v. ↩︎

-

64

Mason and Smith, Dialogue, lxxiii; Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707, ed. K. M. Brown et al. (University of St. Andrews, 2007–24), https://www.rps.ac.uk, 1584/5/14. Buchanan’s Rerum scoticarum historia (1582), an ideological rebuttal of Leslie’s De moribus, was banned alongside De iure. ↩︎

-

65

John Leslie, A Treatise Tovvching the Right, Title, and Interest of the Most Excellent Princess Marie, Queene of Scotland, and of the Most Noble King James, Her Graces Sonne, to the Succession of the Croune of England ([Rouen], 1584); Doran and Kewes, “Joint Iconography”, 61–63. Two years earlier, in October 1582, Mary received a portrait of her son that struck her as quite different from all the earlier ones she had seen, which prompted her to enquire about the artist who had painted it. See a transcription of her letter to Castelnau of 31 October 1582, in George Lasry, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo, “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters from 1576–1584”, Cryptologia 47, no. 2 (2023): 53. ↩︎

-

66

Sowerby, “Negotiating the Royal Image”, 121. ↩︎

-

67

William Dunn Macray, “Second Report on the Royal Archives of Denmark, and Report on the Royal Library at Copenhagen”, in The Forty-Sixth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1886), 36. ↩︎

-

68

David Scott Gehring, Anglo-German Relations and the Protestant Cause (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013), 133. ↩︎

-

69

Orkney and Shetland had been under the Danish Crown but were pledged to Scotland as part of Margaret of Denmark’s dowry when she married James III in 1469. See Thomas Riis, Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot—Scottish–Danish Relations c. 1450–1707, vol. 1 (Odense: Odense University Press, 1988), 18. ↩︎

-

70

See also Fry, “Diplomacy & Deception”, 56–64. ↩︎

-

71

David Scott Gehring, “Introduction”, in Diplomatic Intelligence on the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark during the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James VI, ed. David Scott Gehring (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 9. ↩︎

-

72

Steffen Heiberg, Christian IV and Europe (Herning: Foundation for Christian IV, 1988), 45. ↩︎

-

73

The church was demolished in 1864, and the oaken tablet is now on display in Slottsfjellsmuseet. ↩︎

-

74

According to contemporary observers, James and Hemmingsen debated predestination. However, a near-contemporary manuscript claims that they probed the nature of the Eucharist. The authenticity of this text is, however, disputed. See Riis, Auld Acquaintance, 123; and Holger Fr. Rørdam Kjøbenhavns Universitets Historie fra 1537 til 1621, vol. 3 (Copenhagen: Danske Historiske Forening, 1873–77), 21–22. James owned several of Hemmingsen’s books. See Warner, The Library of James VI. ↩︎

-

75

See Heiberg, Christian 4, 433–37; and Heiberg, Christian IV, 73–77. ↩︎

-

76

Pajung, Dansk–Engelsk Portrætkunst, 18. ↩︎

-

77

Niels Laurits Høyens Skrifter, vol. 1, ed. J. L. Ussing (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1871), 243. ↩︎

-

78

Høyens Skrifter, 243. ↩︎

-

79

Jemma Field, Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 152. See also MacLeod, “Facing Europe”, 79; and Heiberg, Christian IV, 45. ↩︎

-

80

N. L. Høyen, “Katalog over portrætterne på Frederiksborg” (unpublished catalogue, 1831), nos. 95 and 696. ↩︎

-

81

Heiberg, Christian IV, 46. ↩︎

-

82

Other portraits of de Critz from the same period can be found today in Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 9379; Museo Nacional de Prado, Madrid, P001954; Palazzo Pitti, Florence, 1890, 3568; and Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMGrh 816. See MacLeod, “Facing Europe”, 75. ↩︎

-

83

For these miniatures, which are at Jægerspris Castle today, see https://kf7media.dk/museum/jourstuen/v2/obj2.asp?id=125&la=1. Two Hilliard portraits of James were apparently gifted to Christian by the king, but there is no archival evidence to support this. See Sowerby, “Negotiating the Royal Image”, 121. ↩︎

-

84

Horace Marryat, A Residence in Jutland, the Danish Isles, and Copenhagen (1860), 382–83. ↩︎

-

85

Marryat, A Residence in Jutland, 383. ↩︎

Bibliography

Adams, Alison. “The Emblemata of Théodore de Bèze (1580)”. In Mundus Emblematicus: Studies in Neo-Latin Emblem Books, edited by Karl A. E. Enenkel and Arnoud S. Q. Visser, 71–99. Turnhout: Brill, 2003.

Anderson, Kate, with Jemma Field, Catriona Murray, Anna Groundwater, and Karen Hearn, eds. Art & Court of James VI & I: Bright Star of the North. Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2025. Exhibition catalogue: National Galleries of Scotland.

Bath, Michael, and Theo van Heijnsbergen. “Paradin Politicized: Some New Sources for Scottish Paintings”. Emblematica 22 (2016): 43–67.

Beckett, Margaret J. “The Political Works of John Lesley, Bishop of Ross”. PhD thesis, University of St. Andrews, 2002.

Beza, Theodore. Icones, id est verae imagines virorum doctrina simul et pietate illustrium. Geneva: Jean de Laon, 1580.

Beza, Theodore. Les vrais pourtraits des hommes illustres en pieté et doctrine. Translated by Simon Goulart. Geneva: Jean de Laon, 1581.

Blakeway, Amy. “James VI and James Douglas, Earl of Morton”. In James VI and Noble Power in Scotland, 1578–1603, edited by Miles Kerr-Peterson and Steven J. Reid, 12–31. London: Routledge, 2017.

Buchanan, George. De iure regni apud Scotos, Dialogus. Edinburgh: I. Rosseum for H. Charteris, 1579.

Buchanan, George. Rerum Scoticarum historia. Edinburgh: Alexander Arbuthnot, 1582.

Checa Cremades, Fernando. Carlos V: La imagen del poder en el Renacimiento. Madrid: El Viso, 1999.

Courtney, Alexander. James VI, Britannic Prince: King of Scots and Elizabeth’s Heir, 1566–1603. Abingdon: Routledge, 2024.

Craigie, James, ed. The Basilicon Doron of King James VI. Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1950.

Custos, Dominicus. Atrium heroicum. Caesarum, regu[m], aliarumque summatum, ac procerum. Qui intra proximum seculum vixere, aut hodie supersunt. Augsburg: Custos, 1600.

de Passe, Crispijn. Effigies regum ac principum. Cologne, 1598.

Doran, Susan. From Tudor to Stuart: The Regime Change from Elizabeth I to James I. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024.

Doran, Susan, and Paulina Kewes. “Joint Iconography for Joint Sovereigns: Mary Queen of Scots, James VI of Scotland, and the Campaign for Association, c. 1578–1584”. In Women and Cultures of Portraiture in the British Literary Renaissance, edited by Yasmin Arshad and Chris Laoutaris, 49–68. London: Bloomsbury, in press.

Farquhar, Helen. Portraiture of Our Stuart Monarchs on Their Coins and Medals. London: Harrison & Sons, 1917.

Fernández-González, Laura. Philip II of Spain and the Architecture of Empire. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021.

Field, Jemma. Anna of Denmark: The Material and Visual Culture of the Stuart Courts, 1589–1619. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Fry, Cynthia. “Diplomacy & Deception: King James VI of Scotland’s Foreign Relations with Europe, c.1584–1603”. PhD thesis, University of St. Andrews, 2014.

Gehring, David Scott. Anglo-German Relations and the Protestant Cause. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2013.

Gehring, David Scott. “Introduction”. In Diplomatic Intelligence on the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark during the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James VI, edited by David Scott Gehring, 1–50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Goldring, Elizabeth. Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019.

Hearn, Katren. Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, 1530–1630. London: Tate, 1995.

Heiberg, Steffen, ed. Christian IV and Europe. Herning: Foundation for Christian IV, 1988.

Heiberg, Steffen. Christian 4: En europæisk statsmand. Copenhagen Lindhardt & Ringhof, 2017.

Hind, Arthur M. Engraving in England in the Sixteenth & Seventeenth Centuries: A Descriptive Catalogue with Introductions. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Høyen, N. L. “Katalog over portrætterne på Frederiksborg”. Unpublished catalogue, 1831.

Høyen, Niels Laurits. Niels Laurits Høyens Skrifter. Vol. 1. Edited by J. L. Ussing. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1871.

Hutchinson, E. J. “Written Monuments: Beza’s Icones as Testament to and Program for Reformist Humanism”. In Beyond Calvin: Essays on the Diversity of the Reformed Tradition, edited by W. Bradford Littlejohn and Jonathan Tomes, 21–61. Lincoln, NE: Davenant Trust, 2017.

James I. Basilikon Dōron, ou Présent royal de Jaques premier, roy d’Angleterre, Escoce et Irlande, au prince Henry, son fils, contenant une instruction de bien régner. Paris: G. Auvray, 1603.

James I. Apologie pour le serment de fidelité que le serenissime Roy de la Grand’ Bretagne requiert de tous ses sujets, tant ecclesiastiques que seculiers. London: Jean Norton, 1609.

Larsson, Lars Olof. “Rhetoric and Authenticity in the Portraits of King Christian IV of Denmark”. Daphnis 32 (2003): 13–40.

Lasry, George, Norbert Biermann, and Satoshi Tomokiyo. “Deciphering Mary Stuart’s Lost Letters from 1576–1584”. Cryptologia 47, no. 2 (2023): 1–99.

Leslie, John. The Defence of the Honour of the Right Highe Mighty and Noble Princesse Marie Queene of Scotlande and Dowager of France. London [Rheims]: Eusebius Dicæophile, 1569.

Leslie, John. De origine, moribus, et rebus gestis Scotorum, libri decem. Rome: Stamperia del Popolo Romano, 1578.

Leslie, John. De titulo et iure serenissimae principis Marie Scotorum reginae. Reims: Joannes Frognaeus, 1580.

Leslie, John. A Treatise concerning the Defence of the Honour of the Right, High, Mightie aand Noble Princesse, Marie Queene of Scotland, and Douager of France. Leuven: Gualterum Morberium [and J. Fowler], 1571.

Leslie, John. A Treatise Tovvching the Right, Title, and Interest of the Most Excellent Princesse Marie, Queene of Scotland, and of the Most Noble King James, Her Graces Sonne, to the Succession of the Croune of England. [Rouen], 1584.

Lockie, D. M. “The Political Career of the Bishop of Ross, 1568–80”. University of Birmingham Historical Journal 4 (1954): 98–145.

MacLeod, Catherine. “Facing Europe: The Portraiture of Anne of Denmark (1574–1619)”. In Telling Objects: Contextualizing the Role of the Consort in Early Modern Europe, edited by Jill Bepler and Svante Norrhem, 67–86. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2018.

Macray, William Dunn. “Second Report on the Royal Archives of Denmark, and Report on the Royal Library at Copenhagen”. In The Forty-Sixth Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, 1–76. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1886.

Marryat, Horace. A Residence in Jutland, the Danish Isles, and Copenhagen. London: John Murray, 1860.

Mason, Roger A., and Martin S. Smith, eds. A Dialogue on the Law of Kingship among the Scots: A Critical Edition and Translation of George Buchanan’s “De Iure Regni apud Scotos Dialogus”. London: Routledge, 2004.

Mazheika, Hanna. “From Text to Network: Confessional Contacts and Cultural Exchange between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Britain, ca 1560s–1660s”. PhD diss., University of Aberdeen, 2019.

McElroy, Tricia A. “Executing Mary Queen of Scots: Strategies of Representation in Early Modern Scotland”. PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 2004.

Millstone, Noah. “Rex Pacificus and the Short Peace, 1598–1625”. In James VI and I, edited by Alexander Courtney and Michael Questier, 168–99. London: Routledge, 2025.

Molina, Jesús Félix Pascual. “Fidei defensores. Arte y poder en tiempos de conflicto religioso en la Inglaterra Tudor. Enrique VIII y María I y Felipe II”. Potestas: Revista de Estudios del Mundo Clásico e Historia del Arte 17 (2020): 57–84. DOI:10.6035/Potestas.2020.17.3.

Pajung, Stefan. Dansk–Engelsk Portrætkunst. Hillerød: Det National Historiske Museum, 2022.

Paradin, Claude. Devises heroïques. Lyon: Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau, 1551, expanded 1557.

Parshall, Peter. “Prints as Objects of Consumption in Early Modern Europe”. Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 28, no. 1 (1998): 19–36.

Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. General editor K. M. Brown. University of St. Andrews, 2007–24. https://www.rps.ac.uk.

Reid, Steven J. The Early Life of James VI: A Long Apprenticeship, 1566–1585. Edinburgh: John Donald, 2023.

Riis, Thomas. Should Auld Acquaintance Be Forgot—Scottish–Danish Relations c. 1450–1707. Vol. 1. Odense: Odense University Press, 1988.

Rørdam, Holger Fr. Kjøbenhavns Universitets Historie fra 1537 til 1621. Vol. 3. Copenhagen: Danske Historiske Forening, 1877.

Samson, Alexander. Mary and Philip: The Marriage of Tudor England and Habsburg Spain. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

Sharpe, Kevin. Image Wars: Promoting Kings and Commonwealths in England, 1603–1660. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

Silver, Larry. Marketing Maximilian: The Visual Ideology of a Holy Roman Emperor. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Sowerby, Tracey A. “Negotiating the Royal Image: Portrait Exchanges in Elizabethan and Early Stuart Diplomacy”. In Early Modern Exchanges: Dialogues between Nations and Cultures, 1550–1800, edited by Helen Hackett, 119–41. London: Routledge, 2016.

Stewart, Ian. “Coinage and Propaganda: An Interpretation of the Coin Types of James VI”. In From the Stone-Age to the 'Forty-Five, edited by Anne O’Connor and D. V. Clarke, 450–62. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1983.

Stilma, Astrid. A King Translated: The Writings of King James VI & I and Their Interpretation in the Low Countries, 1593–1603. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

Strong, Roy R. Tudor and Jacobean Portraits. 2 vols. London: National Portrait Callery, 1969.

Thomson, Duncan. Painting in Scotland, 1570–1650. Edinburgh: Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1575.